Monday, July 31, 2006

Forest & Mote

Beaten At Their Own Game

Was it because elitist shoppers were repulsed by the low quality of merchandise? Was it because Europeans didn't want their historic cities blighted by big box monstrosities?

No. It was because the Germans were already better at playing the discount retailer game than Wal-Mart.

Part of this was the difficulty of adjusting to new rules. Germany mandates limited business hours by law, so Wal-Mart couldn't win out by being open when German discount stores like Aldi were closed. German law also forbids selling product at a loss -- thus removing Wal-Mart's ability to get people in the door with loss leaders.

The larger problem was that German shoppers turned out to be ruthlessly tight-fisted, and willing to go to multiple stores to get the cheapest price on each item. Wal-Mart makes much of its money off getting people to do all their shopping at Wal-Mart, bringing people in the door with some extraordinarily low prices but making it up with everything else in the basket.

Some 80% of German consumers are about 20 minutes from an Aldi, according to Nestle's research. The hard discounters account for about 40% of the German retail market, compared with Wal-Mart's share of less than 2%, analysts say.I was slightly surprised to hear that bottom-rung discounters accounted for so much of the German market, but it makes sense. Despite being famous for historic cities and luxury cars, the per capita income of Germany is much lower than the US (I recall reading a few years ago that if Germany was a US state, it would be the third poorest in the country in terms of per capita income) and their unemployment is significantly higher. For all that Europe is known for quality food and appliances, it's also known for three to four hundred square foot apartments.

German shoppers are accustomed to buying merchandise strictly based on price, German retail consultants say. They are willing to buy laundry detergent at one store and then go to another to get a better price on paper towels. That behavior is called "basket splitting." It is the antithesis of what American shoppers like: one-stop shopping. A big plank of Wal-Mart's strategy in the U.S. and elsewhere is getting shoppers to turn to it for an increasingly wide array of goods.

German shoppers, used to bagging their own purchases, were turned off by such American practices as clerks who bagged groceries. And some German employees objected to American-style workplace rules such as Wal-Mart's prohibition of romantic relationships between supervisors and employees. A lawsuit by workers forced Wal-Mart to lift its ban.

Though I don't have any particular animosity towards Wal-Mart (though we don't shop there much) it's vaguely pleasing to see them being beaten at their own game.

Sunday, July 30, 2006

What Your 18-Year-Old Needs to Know

But for whatever reason, I was thinking this weekend about things one ought to know before being turned out into the world to college or work of basic training of wherever it is that you head off to at eighteen. This is a pretty rough list, and I'd love to see what else readers would suggest. It's not so much meant to be a sum-and-total of necessary education, but sort of a minimum required list for being civilized and functional.

By the time you leave home at 18 you should:

- Read two out of these three: The Iliad, The Odyssey, The Aeneid

- Read four of Plato's dialoges including Apology and Phaedo.

- Have read all books of the Bible at least once.

- Read Augustine's Confessions.

- Read Beowulf

- Read at least one of the volumes of the Divine Comedy (Inferno or Purgatorio would be the recommended choices).

- Read Introduction To The Devout Life.

- Read The Little Flowers of St. Francis and The Little Way of St. Therese.

- Read Brideshead Revisited and Lord of the Rings.

- Read C.S. Lewis' The Four Loves.

- Read at least one novel by each of the following: Dickens, Austen, Dostoyevski

- Read/see at least four Shakespeare plays including Hamlet and Macbeth.

- Read the Constitution of the United States.

- See Citizen Kane, The Third Man, Casablanca, The Godfather, Lawrence of Arabia, Bridge Over the River Kwai, Chinatown and at least one Hitchcock movie.

- Know how to calculate the profit and loss and balance sheets of a small business.

- Know the basics of how a relational database works (e.g. a database with order, order detail, products, and customer tables)

- Know the basics of how to use excel.

- Know how to calculate compound interest.

- Know how to replace a hard drive, add additional RAM and reinstall an operating system on a computer.

- Speak a foreign language well enough to communicate on a basic level.

- Know how to drive a manual transmission car.

- Know how to change a tire and change your oil.

- Know how to operate basic power tools safely and build simple furniture (like a bookshelf or table).

- Know how to cook at least five different meals.

- Know how to do your own laundry.

- Know how to shoot and clean a rifle and handgun.

- Be able to run mile in under nine minutes.

- Memorize the Nicene and Apostle's Creeds, the Gettysburg Address and at least one piece of poetry longer than 100 lines.

I can't claim to have done all this stuff by the time I was 18, but I never claimed to be fully civilized or fully functional. Still, I wish I had done all this stuff by 18, and it doesn't seem impossible to do so.

------------------------------

MrsDarwin adding on here:

By the time you leave home at 18 you should:

- Know how to change a diaper

- Be able to bake a loaf of bread from scratch

- Hear Handel's Messiah, Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture, and Beethoven's Fifth Symphony

- Know the table of elements

- Be able to start and to finish a conversation politely

- Be able to compose a thank you note, a letter of sympathy, an essay, and a job application

- Know how to read music, and play at least one instrument

- Understand how the human reproductive system works (both male and female)

- Have spoken in public at least once

- Know how to lay a fire

- Know how to thread a sewing machine and sew a straight stitch, and know how to sew on a button by hand

- Have nurtured a simple vegetable or flower garden

- Know how to set a table and use a cloth napkin

- Know how to draw basic three-dimensional shapes

By popular demand:

- Know how to balance a checkbook

Opinionated Homeschooler has some good thoughts on the list.

Also, to clarify a bit -- wanting to keeping the post down to something like a vaguely reasonable length, I tried to make some decisions about scope that would make sense. For instance, I think everyone should have read Winnie The Pooh, but since most people do this by the age of eight, I left it off. Other things, I assumed were covered by higher level items. So I assumed that between calculating compound interest and being able to produce a simple balance sheet, you must therefore also know how to manage checking and savings accounts and deal with a credit car or home loan.

The list was also pretty clearly a Catholic list. If you weren't Catholic, St. Francis, St. Therese and St. Francis de Sales would drop off, though I think anyone in Western Culture would do well to read the Bible, Augustine and Dante.

Opinionated Homeschooler is dead right in adding some Aquinas plus math through calculus (sorry MrsDarwin) to the list, as well as knowing the rules to football, baseball and poker.

The great stumbling block for me was trying to think of what you ought to know about science. Some things are so basic it seemed hardly worth mentioning: Know the names and the order of the nine planet. But the tricky thing with science is that it's not based on a few basic seminal works that you to understand the field. That's what strikes me as the weak point of great books programs where science education consists of reading Origin of Species, Newton's Principia, and several of Einstein's seminal papers. Reading "great works" of science is certainly helpful, but it doesn't really get you there.

I continue to be stumped by the science angle, so I'd be eager to hear suggestions -- seeing as some of our readers know a great deal more about science than I do. The one thing I'm pretty sure at this point should go on is:

- Be able to explain and use Newton's universal laws of motion.

Thursday, July 27, 2006

Art: A Piece of Eternity

There seem to be two basic points of view. The one essentially says that the work of art is itself the artist's statement about the world, and so changing it in any way constitutes attempting to modify the artist's message: essentially making as if he had something other than he did. Thus modifying art is seen as lying and also attacking the integrity of the artist's expression.

The other view sees art as the artist's contribution to 'the conversation' as a specific moment in time. Taken in that sense, changing the work of art consists of making a further contribution to the conversation, and not in any sense falsifying the original statement of the artist.

I'm hesitant to try to nail all this down rationally, in that I am not sure that my beliefs about art are all that rational. (I'm not saying that they're irrational so much as that they are not derived from me sitting down and reasoning out a position.) Still, having thought about it for the past few days I believe I can say that the reason why changing another artist's work strikes me as such a bad idea.

As several people have pointed out, art is a sub-creative act. We imitate God by creating a small fragment of a world, ordered by our ideas of beauty and how the world is (or ought to be). However, there is another sense in which the artist's act is 'godlike', in that the artist is trying to stretch beyond the boundaries of our mortal condition by creating his own 'world' which (if properly taken care of) stands to last many centuries after the artist himself has turned to dust. Thus, the art created by some unknown sculptor in Greece 2400 years ago still conveys a statement that, "Once I lived, and I saw the world thus. Once I created that which was beautiful." Thus, through art, man strives for life after death, through concretizing his thoughts in such a way as to share them with others years, centuries or millennia hence.

Some would call this desire for one's own thought and vision, unchanged by others, to last our the centuries selfish. All very well for the artist, but what good does it do the viewer to have these static artifacts of some long dead person's vision sitting around? To my mind, it actually gives the viewer quite a bit. In viewing the art or reading the words of a long dead artist, we

come to experience as clearly as we ever can experience such things how another person thought and felt and viewed the world. What he was, what he believed the world was, and what he wished to convey to people after his death. Thus, if someone changes the artist's work, that person also robs future viewers of the ability to truly know the artist. When art is changed or destroyed, the artist dies again.

come to experience as clearly as we ever can experience such things how another person thought and felt and viewed the world. What he was, what he believed the world was, and what he wished to convey to people after his death. Thus, if someone changes the artist's work, that person also robs future viewers of the ability to truly know the artist. When art is changed or destroyed, the artist dies again.Now, some artist aren't worth keeping alive for eternity. I'm hesitant to actively destroy art (count me out on book burning, even of really execrable stuff) but at the same time I see no particular reason to take care of art that isn't good, or that is actively bad. But changing art (unless you're creating a wholly new piece based on someone else's original) seems to violate this 'art as eternity' purpose.

If there's an argument against this way of looking at things, I think it's probably that there's some art whose greatness no one questions which is no longer whole. The Venus de Milo is an obvious example. The Parthenon Frieze is another.

These works are of unquestioned value, yet we don't see them as they were originally created. And more disturbing yet, to my assessment, is the possibility that part of what makes these works so appealing is that the slight vagueness that age has imposed upon these works. Were they more beautiful when newly made, or does the fact that we ourselves must fill in the gaps provide a universality that the original, newly-minted, lacked?

High times in the organic aisle

"They've got hemp waffles now!" he exclaimed. "Flying high at the breakfast table!"

"I sure wouldn't give them to my kids," I said. "They're wired enough as it is."

Anyone out there ever tried hemp waffles? I'm mildly curious -- but not curious enough to pay a premium price that exotic waffles command.

Wednesday, July 26, 2006

Let's Not, Please

If Dr. Paabo and 454 Life Sciences should succeed in reconstructing the entire Neanderthal genome, it might in theory be possible to bring the species back from extinction by inserting the Neanderthal genome into a human egg and having volunteers bear Neanderthal infants. This might be the best possible way of finding out what each Neanderthal gene does, but there would be daunting ethical problems in bringing a Neanderthal child into the world again.You do have to wonder sometimes, both about the scientists and 'ethicist' blue-skying about this, and about the NY Times reporting taking this with a straight face and printing it.

Dr. Paabo said that he could not even imagine how such a project could be accomplished and that in any case ethical concerns "would totally preclude such an experiment."

Dr. Lahn described the idea as "certainly possible but futuristic."

The most serious technical problem would be creating functional chromosomes from Neanderthal DNA. But ethical questions may be less surmountable. "My first consideration would be for a child born alone in the world with no relatives," said Ronald M. Green, an ethicist at Dartmouth College. The risk would be greater if, following the plot line of Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein," a mate were created as a companion for the lonely Neanderthal. "This was a species we competed with," Dr. Green said. "We would not want to recreate a situation of two competing advanced hominid species."

But Dr. Green said there could be arguments in the future for resurrecting the Neanderthals. "If we learn this is a species that was wrongly pushed off the stage of history, there is something of a moral argument for bringing it back," he said. "But the status quo is not without merit. Curiosity alone could not justify what could be a disaster for both species."

Something Rotten in the State of Literature

One of the commenters linked to an article in the New York Review of Books on the same subject which is also very much worth a read, if only to hear the sad tale of how the phrase "the invaginated eyeball" came to be presented in all supposed academic seriousness.

It all reminds me of the high-school-clever comeback I developed by Junior and Senior years when people kept asking me "if you're so into books, why aren't you planning to study English?" Answer: "Why, because I like literature." In all too many of today's elite colleges, though who actually love the written word (especially if they love it for what it is rather than what can be done to it) would be well advised to stay far away from the English department.

Tuesday, July 25, 2006

Out, damned spot

2. I was finally overcome by my disgust for the nasty carpet.

3. My two youngest siblings (13 and 15) are going to be staying with me for a week.

Add it all up, and you get a New Look in the living room.

No, the carpet isn't going, but it's being cleaned. Baby will be crawling soon, and I feel that I can't in good conscience place her on the living room floor in the condition it's in now. But since the cleaning is scheduled for next week, it seemed like this week would be a good time to try and paint the living room, especially since I have some built-in help and babysitting with my siblings coming out. Making younger siblings work when they visit is another way of saying "I love you."

And since I already threw out the old couch, it seemed as good a time as any to get a new one, especially with visitors coming. Thanks to the miracle of craigslist.com, I found a couch I liked in the afternoon and picked it up that evening. In 24 hours I've gone from this:

(bonus shot of our girls [first and third] early last year)

to this:

(That's not my living room, silly! But it is my couch now, and woe betide the first person who spills something on it.)

If everything goes as planned, I might post some pictures next week of the Extreme Living Room Makeover, Darwin edition.

Akin on Embryo Adoption

I was somewhat surprised that a majority of the commenters seemed to be at odds with Akin's stance. I wonder if, with all of the moral issues which Catholics are used to opposing such as cloning, IVF, surrogate motherhood, etc. that the concept of embryo adoption suffers a certain guilt by association in the minds of many conservative Catholics, because it 'looks too much like' IVF or cloning.My own instincts are with the second group--that it is morally permissible to adopt embryos in order to keep them from dying.

To my mind, the definitive moment of reproduction is conception. When that happens is when you have a new human being. What happens to it next is not reproduction, because the reproduction has already taken place and we have a new person. What follows (implantation in the womb and subsequent gestation) is simply caring for a new person who already exists and thus is not subject to the same kind of moral unalterability as the act of reproduction itself.

In other words, human reproduction is inviolable, which is why IVF (like adultery) is wrong, but most of what is happening during pregnancy is not reproduction. A new human is produced--and thus reproduction takes place--at the very beginning of pregnancy. What follows is growth, development, and care.

Whatever the reason, I think the reproduction followed by nurturing description which Akin uses is one of the main differences between Catholic teaching and mainstream American feeling these days. My impression is that many people envision all of early pregnancy or in extreme cases pregnancy as a whole as one long act of reproduction, which doesn't actually produce 'a baby' until very late in the process. This may make intuitive sense to many people at an emotional level, but it presents problems physically, since there is a continuity of existence throughout the development of the embryo/fetus/baby from conception to birth and beyond. From an empirical perspective (and though I by no means hold that the empirical perspective is the only or even the most important way of viewing the world -- it certainly is the best way we have of understanding the physical world around us) it is conception at which something clearly happens. What occurs after that is clearly development. A great deal of development to be sure, but development within a continuity of existence. Any other dividing line must be based upon how some external observer feels about the unborn child -- and I am deeply skeptical of any system which claims that what something is depends upon how others perceive it rather than upon its own being.

Monday, July 24, 2006

Unfertilized Embryos?

So it's hardly surprising that one of CNN's blonde talking heads (Fox isn't alone in this affliction, it seems) had a gaffe on air in which she talked about how stem cell researches only wanted to use 'unfertilized embryos'.

However, it's significantly more disappointing to see someone from ScienceBlogs making the same mistake. "...using unfertilized and otherwise discarded embryos for research that might lead to life-saving cures." You can have an unfertilized egg, and you can have a discarded embryo, but having an unfertilized embryo is an impossibility by definition.

And people accuse us of not belonging to the 'reality based community'...

The Source of Middle East Conflict

U.S. Sen. John Kerry, D- Mass., who was in town Sunday to help Gov. Jennifer Granholm campaign for her re-election bid, took time to take a jab at the Bush administration for its lack of leadership in the Israeli-Lebanon conflict.Well don't I feel small. Clearly things would be pretty peachy between Israel and it's Arab neighbors if only we had someone with more diplomatic experience in the White House.

"If I was president, this wouldn't have happened," said Kerry during a noon stop at Honest John's bar and grill in Detroit's Cass Corridor.

Bush has been so concentrated on the war in Iraq that other Middle East tension arose as a result, he said.

"The president has been so absent on diplomacy when it comes to issues affecting the Middle East," Kerry said. "We're going to have a lot of ground to make up (in 2008) because of it."

Saturday, July 22, 2006

He Ain't A Chimp, Sir. He's my cousin.

The Neanderthal genome project was unveiled yesterday in a news conference held at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. Institute scientists plan to complete the project in two years in collaboration with the American biotechnology company 454 Life Sciences, a subsidiary of the Branford, Conn.-based CuraGen Corp. 454 has developed a speedy new approach to studying DNA.Neanderthals are an interesting topic, both scientifically and in a wider human sense, in that they appear to have been our closest non-ancestral relatives in the Homo genus. There is, apparently, controversy about exactly how to classify Neanderthals. I had recalled reading that they were classified as a sub-species of our own species (they were classified as Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, while we are Homo sapiens sapiens) but glancing around at some current information on the web, it looks like classifying them as a separatspecieses (Homo neanderthalensis). This may be because the current understanding is that both we and the Neanderthals separately descended from Homo erectus.

Knowing more about Neanderthal's genes should give scientists a new window into human evolution. "The Neanderthal will be like modern humans in most ways, but more like a chimpanzee in others," said Svante Pääbo, the Max Planck geneticist who will head the effort.

Most scientists believe modern humans and Neanderthals come from a common ancestor but diverged about 500,000 years ago. Neanderthal was a heavy-boned hominid who was adapted to cold, made use of stone tools, and thrived in Europe and Asia until about 30,000 years ago.

One of the intriguing things about Neanderthals (both in a general and in a speculatively religious sense) is the question of whether or not we would recognize them as human. Much scientific speculation (and so far as I know there's little more than speculation on this point) centers around whether Neanderthals were capable of abstract thought, and whether they posses complex language skills. They did fashion tools (as did earlier hominids back to aprox 2 million years ago) but their tools were much simpler than those made by homo sapiens. There is also some evidence of ritual burials with artifacts, which many anthropologists consider to be evidence of a religious sense. All of which is interesting, of course, but non of which can answer the (probably unanswerable question) general question, "Where they 'human' in an essential sense?" and the more specifically religious one: "Did they have souls?"

One thing that mildly annoyed me about the WSJ article, however, was its several times repeatecuriosityty about which parts of the Neanderthal genome would prove to be similar to humans, and which would be 'more like chimps'. I'm certainly open to correction from the more knowledgeable, but I'm not clear why one would consider Neanderthals to be more similar to chimps than we are. Both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals are believed to be descended from a single common ancestor, Homo erectus. Given that, although modern humans and Neanderthals clearly would have had genetic differences, neither one would be 'closer' to chimps than the other, since the ancestral line of both split from chimps at the same time. Neanderthals might be genetically more similar to chimps in some ways, but more different in others -- but it seems like if we are both 'sibling' species descended from Homo erectus, that we'd be roughly equally distant from our 'cousins' the chimps. The "how far from chimps" line of thinking seems to spring from the "humans are descendants of chimps" line of thinking rather than the far more correct "humans and chimps share a common ancestor".

Thursday, July 20, 2006

You Can't Clean a Flick

I think part of the problem is something that our increasingly commoditized entertainment industry has let itself in for. It's rather hard to see many big name movies these days as works of art, and so in a sense, how can we be surprised that people think they should be able to order them a la carte. While 'content' heavy movies such as Pulp Fiction, The Godfather and Full Metal Jacket are clearly works of art (which one may like or dislike, but without question represent a unified artistic vision of the creator) the latest committee-written children's comedy or big action spectacle does not, and so perhaps we shouldn't be surprised if someone wants to see Madagascar, Big Daddy, The Fast and the Furious or MI3 minus what they consider gratuitous objectionable material.

Another problem is that many Christians have an overly checklist-oriented system of morality in regards to art. In this sense, I think it's important to take a minute to think about what art is: an act of subcreation. When a writer or director puts a story in front of us, we see not merely the events that take place within the story, but also a view (which may be subtle or explicit) of how the artist believes the world to work, and what he believes it means. A narrative piece of art is not simply a sequence of events taking place within our world (which we as Christians believe was created by God) but rather a sequence of events taking place within the artist's own world, which operates according to laws created (implicitly or explicity) by the author which may be similar or dissimilar to the world in which we live.

Take one of the Lethal Weapon movies. If you cut out all the swearing, and any particularly graphic elements of violence, would you really have any more moral a movie? The relationships between the characters, their priorities and ideas of happiness would remain the same. The elements of 'content' may be the most clearly objectionable element to a parent, to the extent that you don't want your eight-year-old announcing that he's "too old for this shit", but allowing a fairly young child to see the Lethal Weapon movies (even expurgated of all 'content') accustoms him or her to a set of assumptions about how 'the good guys' live their lives which may be rather far from what a Catholic parent would want.

Similarly, the problem with Titanic from a moral perspective is not just what goes on in the steamy Model-T, or the scene of Kate Winslet being drawn in the nude (though a sufficiently un-formed child could certainly be led into sin by one of these) but with the entire understanding of what love is (and the place of sex in it) presented in the movie. Nor would Jerry Maguire (boy, I'm dating myself with all my examples, eh?) be any more moral if the bouncy sex scenes and pervasive use of a certain Anglo Saxon term were removed. The problem with that movie is with its understanding of what integrity, love and sex are at a more intrinsic level.

There are movies with a great deal of "objectionable content" (Rob Roy, Pulp Fiction, Black Hawk Down, Barry Lyndon, The Funeral, to name just a few) which nonetheless have important, sometimes even deeply moral messages. There are other movies which are crass and worthless at heart, no matter how many of the trappings are skimmed away.

But what, you ask, of the movie which a parent believes to be essentially sound, yet contains elements they don't want a child exposed to? Wait, it seems to me. Few children are going to waste away physically or intellectually because they're forced to wait till they're ten before seeing some movie that their friends saw at 6 or 8. If it's a good movie, with some parts that the child isn't yet able to contextualize within the moral framework, then it will keep. And if it's not that great a movie anyway, the kid will be better off. I'm not one for exposing children to the darker corners of the world before they're ready, but I'm also not one for papering over the problems in the world (what's the traditional Protestant image of grace: like snow on a dung hill?) in order to present a book or movie to a child earlier.

As a young child (say six to ten) I was a huge fan of classic Star Trek, yet my parents didn't let me see Wrath of Kahn (by far the best of the movies) until I was nine or ten. They were concerned about some of the language and violence, but more so about Kirk's ex-lover and their out-of-wedlock son who are characters in the story. And indeed, having fixed on Kirk as a hero, when I did finally see it the one hard thing for me was dealing with a character I'd come to see as a hero doing something clearly against our moral code. The degree of distress it caused me would probably seem silly to most outsiders, but at the time it was a pivotal learning opportunity -- that people come with good and bad sides, and you can't allow your admiration for certain qualities of a person outweight your ability to view the rest of their actions through an objective moral lens. And yet that, at the same time, someone who does something you consider very wrong is not thus some sort of human monster without admirable or redeeming qualities. I like the movie to this day, but I wouldn't show it to a child who wasn't yet morally mature enough to deal with the same issues.

So while I have little opinion as to whether CleanFlicks is behaving legally, I certainly think their business model is based on a morally shallow understanding of art and of life.

Wednesday, July 19, 2006

Inside I'm Screaming

Two questions:

1) How did this isolated leg turn up on my bathroom floor.

2) Where's the rest of the roach?

I'm off to call Orkin now.

Are Dogs Intelligently Designed?

However, some recent genetic research sheds a bit of interesting light on the evolutionary history of dogs. Researches sequenced the mitochondrial DNA of several breeds of dog, plus modern grey wolves, to which dogs are believed to be closely related. Their results suggest that modern dogs were domesticated and removed from the wolf gene pool about 15,000 years ago, very recently by an evolutionary timescale. However, during that time dogs have built up and retained far more minor genetic defects than the wolf population -- and also much more genetic diversity (thus allowing all the different breeds of dog).

The researches believe the cause of this is that with human care, genetic changes which might have reduced a wolf's chances of survival are allowed to flourish among the dog population because they receive human care, and are thus under less pressure from natural selection. Thus, the modern genetic diversity among dogs is primarily the result of human care. I hardly think this is what the Discovery Institute had in mind, but we now seem to have found a population whose current genetic makeup is the result (in part) of intelligent design -- or at least of pampering.

UPDATE: Razib has some additional thoughts on dogs and human influenced evolution over at Gene Expression.

Tuesday, July 18, 2006

Write an Essay, Win a House

The entry fee is $100, but that's not much to pay for a house, all things considered. May the best essayist win!

Emailed to me by the fabulous Alana Antolak.

Prayer, Time and Uncertainty

Now, on the face of it, this seems downright silly, since the test has already been taken and scored, and the scores (whatever they are) are already written down on the paper on the envelope. Even assuming that Papa G has the power to influence the test scores, it's now too late.

Maybe thinking about all this much is a mistake right there, as prayer is (for Christians) at attempt to communicate with a being much different from ourselves. Sacred scripture gives us a number of analogies by which to think about prayer, yet all of them cast the interaction between God and man via prayer in more directly human terms -- as in the parable of the old woman and the dishonest judge.

Taking it that God is both all knowing and outside of time, there is in theory no reason why one should not offer prayers of supplication regarding the outcome of an event which has already occurred but the result of which you are not yet aware of. One would assume that God would have been aware of those prayers before the event occurred. Yet is seems doubly odd to offer prayers after the fact about an event in which you yourself were the primary player. Thus, if you took a multiple choice test, but have not yet received the grades, it seems odd to offer prayers asking God to help you do well on the test, since any last minute inspiration you might have had while taking the test has already taken place. The fact that you don't yet know your score doesn't change the fact that you have already recorded answers which are (by the pre-set criteria of the test) either right or wrong.

It shouldn't come as a surprise that our interactions with the infinite are something that we find difficult to understand. As I said, perhaps one does well not to think on the odder elements of all this too deeply.

Perhaps another thing to recall is that traditional Catholic spirituality teaches that prayers of supplication should be thought of as the least of our prayers. More important are prayers of praise and prayers of thanks. We are, after all, not in nearly as good a position to know what is best for us as God is. The old lady in the parable harangues the dishonest judge constantly demanding that he give her justice. But in her case, she has a better knowledge of justice than the judge does. When we beseech God, the situation is the opposite. Not my will, but Thine be done.

Monday, July 17, 2006

Total War and the Fortress State

The other thing to note is that while Israel has been striking purely military targets in the sense that it is not aiming at civilians (though that has not spared it from international opprobrium), Hezbollah has been firing exclusively at civilians. Indeed, they can do nothing else because their weapons are presently so crude that they can only hit the vast sprawls of which modern urban life is made.This tactic should be familiar to our ears, since the doctrine of 'Total War' was that which motivated the city-levelling bombing of World War II. The other motivation for city-wide bombing in WW2 was of course that then-current technology often only allowed precision of several hundred years to (in poor conditions) several miles in bombing precision, thus making city or at least neighborhood-sized targets the only viable ones.

Radical militias attacking Israel are in a similar situation, in that the rockers and artillery that they have are generally so out of date that their aim only allows random terror bombing -- though given their states goals of wiping Israel from the face of the earth, it's unlikely they would behave any differently no matter what technology they had available.

Over the weekend I finally had a chance to start reading Victor Davis Hanson's new book A War Like No Other, about the Peloponnesian War, fought 2400 years ago betwee Athens and Sparta. That conflict continues to be studied to this day (Thucydides' History is required reading as the US Army War College) in part because it represented the first total war in history. Athens, which in the process of spreading democracy through the Hellenic world had also made itself the effective imperial power of Greece, exacting a huge annual tribute from it's many client states and beseiging and levelling any state the refused payment, had effectively made itself independant (at least for short periods) from its local agricultural resources. When the invading Spartans took the standard classical Greek tactic of ravaging the fields around the walled city and waiting for that provocation to cause the city to send its army out to defend the farmland, the Athenians simply sat inside the walls and ignored them, while sending naval expeditions out to raid the Peloponnesian coastlines.

The earlier approach to warfare in ancient Greece had always been one in which an enemy appeared, ravaged the farmland around the city, and the native army then came out to meet them in open battle on the plain. The battle generally lasted only one day, and the result determined the outcome of the campaign. By breaking this model and refusing to right in open battle, Athens essentially chose to fight a war in which the only way to defeat here was through destroying her entire empire -- which is what eventually happened over the next 27 years.

Hezbollah and Hammas are waging war against the state rather than an army for wholly different reasons. They know they can't survive open, direct battle against the IDF, and so they hide behind the civilian populations of neighboring Arab areas while attacking the civilian population of Israel, and hoping to eventually wear their enemy down -- a tactic which in addition to creating protracted suffering in the region stands no chance of succeeding in their stated aim of destorying Israel.

Classical hoplite warfare was essentially an agreed method of war whereby conflict was short and the suffering of war was primarily placed upon soldiers themselves clashing in direct battle. Modern assymetric total war is an attempt to protract a conflict while placing the majority of the suffering upon the civilians of both sides, as a way of conserving the military resources of a numerically small combatant force, and wearing down the opposing side through seemingly endless suffering.

Friday, July 14, 2006

And So It Begins?

Israel brought its offensive in Lebanon to south Beirut Friday, with warplanes blasting residential neighborhoods, destroying Hezbollah's headquarters and targeting road links. Airstrikes cut the main highway to Syria and exploded fuel tanks. Warships blockaded Lebanon's ports for a second day.A look at the map of the Middle East shows not only how wide spread an Israeli war against Syria and Iran would be, but also that we'd be right in the middle of it, since the only way to Iran is through Iraq.

Hezbollah said the residence and office of its leader, Sheik Hassan Nasrallah, had been destroyed, but that he and his family were safe. Palls of smoke rose from the Haret Hreik neighborhood in the late afternoon, after four huge explosions shook the capital. They were followed minutes later by a fifth blast.

Lebanese guerrillas retaliated for the airstrikes with a barrage of Katyusha rockets throughout the day, hitting more than a dozen communities across northern Israel....

Israel's escalating incursion into Lebanon could turn its border fight with militant Islamists into a regional war that Israel is openly warning might lead to Syria, and beyond that to Iran.

Already the violence has engaged the Israeli military on two fronts, against Hezbollah militias in Lebanon to the north and Hamas forces that control the Palestinian government in the Gaza Strip to the west. Israel now is fighting not with Palestinians or Arab nations, as in the past, but with the forces of radical Islam.

And the Israelis are bluntly saying that the blame for the violence by those forces lies in large measure with the governments of Syria and Iran for giving them support and encouragement -- an assertion that could put the U.S. and Israel on diverging paths in the crisis. "The real masterminds [behind these acts] are in Tehran and Damascus," Daniel Ayalon, Israel's ambassador to Washington, said Thursday. The international community "needs to call Iran to task," he said.

Israel, however, is in a terribly difficult position, in that it is under constant low-level attack by organized militant groups which Syria and Iran tollerate and fund, but are not considered formally 'responsible' for. And looming over is all is the knowledge that if there is going to be a wider Middle East war, it would be far better to have it before Iran has nukes than afterwards.

Party like it's 1986

What was amusing, though (and we're only part-way through the series, so I don't know how they handle this toward the end) was the very first episode, with its overview of English in the world today (which is to say, 1986). There's a big focus on India, of course, as one of the major sources of non-ethnic English speakers, but in trying to be up-to-the-minute, the program also spotlights Valley Girl slang, surfer talk, and "gay English". The gay section is just lame (it consists of a gay comedian doing a routine about the term "queen", and it wasn't even funny). And hoo boy, does the Valley Girl ethos seem dated. I mean, gag me with a spoon! As if! Grody! Meanwhile, the surfers sat about saying "Rad!" and "Tubular!" to one another and looking a bit stoned. There was also a very short bit of computer-speak. Obviously the producers were trying to cover all the latest trends, though it seems a cinch to me that computers were going to make more of an impact on the vernacular than spoiled California kids.

I take it there's a section that looks a bit a rap music, which intrigues me, since 1986 was before my radio-listening days. I wonder if we'll hear D.J. Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince? ("I Think I Can Beat Mike Tyson", anyone?) So far, though, we've been treated to the beauty and grandeur of spoken English through the ages, from the early Celts to Shakespeare.

English is tubular, dudes.

Thursday, July 13, 2006

Gender, Terminology and Reality

Prof. Barres is transgendered, having completed the treatments that made him fully male 10 years ago. The Whitehead talk was his first as a man, so the research he was presenting was done as Barbara.Notice the phrase "made him fully male". Now, I've read the basics of what sex change treatments involve, and it seems odd to talk about how such treatments "made him fully male". Certainly, the treatments may have made him look about as male as he can be made to look. But if we take "male" to be a biological category, it's silly to talk about someone being "made fully male". Either you're male, or you're not.

Being first a female scientist and then a male scientist has given Prof. Barres a unique perspective on the debate over why women are so rare at the highest levels of academic science and math: He has experienced personally how each is treated by colleagues, mentors and rivals.

Now, I have enough acquaintances who are into such issues that I know the standard argument goes: "Well, physical gender is really not nearly as clear cut as you imagine. What about hermaphrodites? Close examination suggests that gender isn't a binary attribute, it's a spectrum."

Obviously, how you answer this contention with whether you think there is any kind of teleology implicit in biological structures. I'm not necessarily talking teleology in the sense that ID advocates use the term, but rather the more basic concept of certain biological attributes having a defined function, regardless of how that function got there. In the case of gender, the male/female attributes clearly exist, in the biological sense, in order to allow sexual reproduction, an innovation which first appeared (according to standard interpretations of the fossil record) about 1.2 billion years ago, which has allowed more rapid genetic diversification and endless fodder for the cheaper sort of fiction.

For sexual reproduction to occur, a functional male and function female of the species are required. In this sense, while it's undeniable that various genetic defects can effect the appearance and/or function of human gender attributes, it seems to me clear that the textbook definitions of male and female represent not merely points on a spectrum, but what (at least for the perpetuation of our species -- something I'm generally in favor of) male and female "ought" to be. This doesn't mean that people with physically malformed gender attributes are less human -- unless you accept the idea that one's humanity is a matter of degree rather than identity (something which I unquestionably reject) -- but it does mean that gender is indeed binary by nature, even if some instantiations of that nature are imperfectly formed. It also means that talking about a female undergoing treatments to become "fully male" currently not only impossible, but unimaginable -- since it's not possible to make a female function as a male in any biologically meaningful sense.

Which leaves one to ask, why is it that our culture's ways of discussing gender of drifted so far from what gender actually is?

Let not the precious time be lost

And speaking of placing one foot in front of the next, I'm physically tired. Darwin and I have finally come to terms with the fact that our average metabolisms and relative youth won't last forever, and have decided to take steps to get and stay in shape. And that means running. (Well, for Darwin it means running -- for me it means a mixture of walking and jogging and hoping to God that no one drives by and sees me.) The fickle bathroom scale is putting me at a pound or two less, but the progress is hard and slow and sometimes seems pointless.

There are times when all I want to do is just read my book, for Pete's sake, but real life keeps trying to intrude. Julia's potty training is going oh-so-slowly because she doesn't seem to care about it, and it's getting to where I don't either. Baby is a good-natured little thing, but she gets tired of sitting in the recliner with my book long before I do, and she loathes the computer. Eleanor wants to raid the fridge or climb up to various shelves to get picture albums or dishes to play with. And I just want to be left alone to do my own thing, because what's the point of wiping down the table or folding the laundry when I'm just going to have to do it again tomorrow? LEAVE ME ALONE and let me read!

Yesterday afternoon as I was standing amidst the wreckage of the kitchen, I realized that my shirking of responsibilities was more than mere laziness or burn-out. It was sloth -- "not merely idleness of mind and laziness of body: it is that whole poisoning of the will which, beginning with indifference, and an attitude of 'I couldn't care less', extends to the deliberate refusal of joy and culminates in morbid introspection and despair."* Sloth can take different forms -- Tolerance, Disillusionment, Escapism. And I was worn-out with being slothful, and I was ready to combat it.

So I pulled out our copy of Dante's Purgatory to discover what the penitents on the Fourth Cornice did to atone for their sloth, and what prayer they chanted. Upon flipping to Canto 18, I at once found the passage where the souls cry to each other, "Quick! Quick! Let not the precious time be lost for lack of love! ...In good work strive, till grace revive from dust!" The slothful souls are the only ones in Purgatory who are given no prayer to pray -- their prayer is in their labor.

And the labor that makes up their penance? Ceaseless activity. Namely, running.

*The description of sloth is taken from the commentary on the Image of Sloth in Dorothy Sayers' translation of Purgatory, Penguin, 1955

Death To Roaches

Some people seem to think this is a sign of a cruel God, or no God at all. But from where I sit, the roaches had it coming to them. (And as a habitual roach smasher, I obviously don't have any issue with roach death and suffereing -- though in all honestly I doubt a roach experiences much of either. Of course, I tend to take it to wasps too...) Here are some highlights, though for the sake of any readers who may be eating I haven't pulled in any of the pictures. Click through to see the full glory of it all.

As an adult, Ampulex compressa seems like your normal wasp, buzzing about and mating. But things get weird when it's time for a female to lay an egg. She finds a cockroach to make her egg's host, and proceeds to deliver two precise stings. The first she delivers to the roach's mid-section, causing its front legs buckle. The brief paralysis caused by the first sting gives the wasp the luxury of time to deliver a more precise sting to the head.

The wasp slips her stinger through the roach's exoskeleton and directly into its brain. She apparently use ssensors along the sides of the stinger to guide it through the brain, a bit like a surgeon snaking his way to an appendix with a laparoscope. She continues to probe the roach's brain until she reaches one particular spot that appears to control the escape reflex. She injects a second venom that influences these neurons in such a way that the escape reflex disappears.

From the outside, the effect is surreal. The wasp does not paralyze the cockroach. In fact, the roach is able to lift up its front legs again and walk. But now it cannot move of its own accord. The wasp takes hold of one of the roach's antennae and leads it--in the words of Israeli scientists who study Ampulex--like a dog on a leash.

The zombie roach crawls where its master leads, which turns out to be the wasp's burrow. The roach creeps obediently into the burrow and sits there quietly, while the wasp plugs up the burrow with pebbles. Now the wasp turns to the roach once more and lays an egg on its underside. The roach does not resist. The egg hatches, and the larva chews a hole in the side of the roach. In it goes.

The larva grows inside the roach, devouring the organs of its host, for about eight days. It is then ready to weave itself a cocoon--which it makes within the roach as well. After four more weeks, the wasp grows to an adult. It breaks out of its cocoon, and out of the roach as well. Seeing a full-grown wasp crawl out of a roach suddenly makes those Alien movies look pretty derivative.

Wednesday, July 12, 2006

Formalisms, Biology, QM and more...

Zippy's essential contention is that evolutionary theory is not a formalism (such as the Coppenhagen school of QM) but rather a general interpretive framework of events. The comments section on Michael's post is worth reading, if only to see if I've completely got out of my depth in trying to discuss QM, define science, and so on.

Tuesday, July 11, 2006

The Oracle of Starbucks

Think you know your personality type? Think again. The Oracle of Starbucks will tell you all you need to know about yourself (and then some) when you describe your Starbucks order of choice.

I rarely go to Starbucks (if I ever have an urge to drink coffee I can rely on Darwin to brew me a fine cup), so I had to search my memory for what I ordered last time I was there, but I think it was a tall tazo tea in some kind of orange flavor.

Darwin opted for a tall straight espresso.Behold the Oracle's wisdom:

Personality type: Pseudo-intellectual

You're liberal and consider yourself to be laid back and open minded. Everyone else just thinks you're clueless. Your friends hate you because you always email them virus warnings and chain letters "just in case it's true." All people who drink tall tazo tea orange are potheads.

Also drinks: Sparkling water

Can also be found at: Designer grocery stores

H/T Fructus VentrisBehold the Oracle's wisdom:

Personality type: Asshat

You carry around philosophy books you haven't read and wear trendy wire-rimmed glasses even though you have perfect vision. You've probably added an accent to your name or changed the pronunciation to seem sophisticated. You hang out in coffee shops because you don't have a job because you got your degree in French Poetry. People who drink tall straight espresso are notorious for spouting off angry, liberal opinions about issues they don't understand.

Also drinks: Any drink with a foreign name

Can also be found at: The other, locally owned coffee shop you claim to like better

Islam's Martin Luther: Mohammed Wahhab?

I know Americans tend to think that being anti-authority means being liberal. But by almost every definition of the Left today — to the extent such definitions are applicable — the Protestant reformations and revolts were conservative events. Protestants were not rebelling against the oppressively theistic rules of the Church, they were rebelling against the Church's worldly compromises in regard to those rules. (Think of the selling of indulgences — a modern-day liberal would love such soak-the-rich scams.) Martin Luther was motivated by piety, not by secular liberalism. The Catholic Church was burning books and heretics pretty selectively by the time of the Reformation. The Protestants adopted the practice wholesale.I think Goldberg correctly latches onto one of the key contradictions in traditional English/American discussions of the Reformation. Because many in the modern secular English speaking world consider themselves heirs on the Enlightenment, and because in Protestant England the Reformation came to be seen at the beginning of the abandonment of 'Romish Superstition', the established myth seems to be that the Reformation was itself full of Enlightenment-style thinkers. Yet Luther and Calvin would have unconditionally consigned to hell much of what the Enlightenment stood for. In their own way, the reformers had more in common with medieval piety movements turned heretical (like the Fraticelli) than with Voltaire and Rousseau.

If you travel around peace-loving Switzerland, for example, you'll discover that a couple of centuries worth of art is simply missing, because Protestant iconoclasts burnt it in giant bonfires to fuel their fondue-pots of religious fervor. The Catholic Church, meanwhile, has a very nice art collection, which includes depictions of lots of pretty-naked ladies and a few naked pretty ladies....

Which brings me to Islam.

The fact is that the Arabs have had their Muslim Martin Luthers and John Calvins. One was the 18th-century Mohammed Wahhab, founder of Saudi Arabia's austere version of Islam called Wahhabism....

In the latest issue of The National Interest, Adam Garfinkle notes that "The Wahhabi version of Sunni Islam is neither traditional nor orthodox. It is a slightly attenuated fundamentalism that dates only from the end of 18th century. . . . [A]s recently as 50 years ago the large majority of Muslims considered Saudi Wahhabism to be exotic, marginal and austere to the point of neurotic."

We all know that the Wahhabis, like their Taliban pupils, are fanatical iconoclasts. But it's rarely noted that they have always been fanatical iconoclasts. In 1925 Ibn Saud, the patriarch of the current Saudi dynasty, ordered the destruction of all the tombs, monuments, and shrines in Mecca and Medina. Crowds of fanatics destroyed the graves of Mohammed's family and even his house. Mosques were torched. Traditional Muslims barely stopped the Wahhabis from destroying Mohammed's grave itself.

This runs completely against the stereotype of "conservative" Saudi Arabia, until you think of mobs of similar "reformers" burning Catholic churches and artwork all across Europe (though I can't see Christians of any denomination seeking to destroy Christ's tomb)....

What modern commentators are really wishing for is an Islamic Bishop Spong.

Dreher on Spiritual Fatherhood

Not long ago, I thought about how rarely I have ever looked upon the pastor at any parish where I've been worshiping as any sort of spiritual father, or an authority figure in all but the minimal sense. That is, I've only been able to take him seriously as "magician or ritual functionary," because there is very little if anything fatherly about him. Clerics these days -- and I'm not just talking about Catholic priests, so cool your jets, you usual suspects -- too often comport themselves as Best Buddies, or mere Therapists. Maybe it's just me, but I've always thought that there was something really wrong, and ultimately undermining, about being part of a spiritual community that had no spiritual father....Now, this is certainly not the first time that I've run into someone worrying that priests these days aren't filling their necessary roles as father to the parish. But since Dreher concluded his post with a request for comment from others on whether they felt they had experienced spiritual fatherhood in their churches (Catholic or otherwise) I started thinking, What exactly is 'spiritual fatherhood' anyway? Come to that, what exactly is 'fatherhood' or 'fatherliness' in the more general sense?

Lately I've been having a lot of odd memory moments in which, while dealing with the girls, some memory from my own early childhood suddenly comes back with the realization, "Oh, that must be what was really happening." In many ways, after just over four years on the job, I still feel like I'm just 'faking it' until I 'really' know how to be a father. Increasingly, however, I realize that this isn't just some introductory stage, this is the real thing. And indeed, when I expressed the feeling that I still hadn't figured fatherhood out to my own father, just a few months before his death, he replied that after 27 years he still felt like he was faking it as well. And the end of the day, fathers are just men who have kids. And we try to muddle on through and do the best job that we can at raising our children, setting a good example, bringing them up in the the love of God and Church, and teaching them however much or little we know.

This is not to say that 'fatherliness' is not an important attribute. It's just that I very much doubt that many people feel fatherly in the stereotypical sense that many of us have culturally ingrained. That doesn't mean that your father should be "Best Buddies, or mere Therapists", but rather that as a father you often look fatherly to your children when you don't feel fatherly yourself. Fatherliness is perhaps more a product of the difference in age, experience and understanding between father and child than it is a trait specifically possessed by the father himself. I try to explain things and mete out justice to my children as best I can, yet feel like I have none of the gravitas that my father did. Yet, it may well be that my children think I do. And that they, in turn, will feel like they are all at sea, muddling along as best they can, when it comes their turn to be parents.

How does all this apply to priests? Well, a priest has a far more difficult job, in that he's being asked to provide a sort of spiritual fatherhood to people who are often his own age, or indeed older. And a priest is, after all, at the human level just a guy who has been ordained. Certainly, becoming a priest must be a life-changing event (as is having a child) but at the same time a priest must look back to his youth and his childhood and think, "I'm not really a different person than I was before -- how can I possibly provide the 'fatherhood' that people expect of me?"

The answer, perhaps, is the same as for biological fathers: Muddling through. Trying to provide wisdom and discipline as needed. Being honest about your limitations, without taking the cowardly path of "I just don't know, you'll have to figure that out for yourself" unnecessarily. At the least, a priest can be an honest, prayerful and hard working man. Some parishioners, seeing the priest as being vastly more knowledgeable about the faith, may see in his teaching and guidance the image of a father (or more precisely, a dim reflection of The Father.) Others may see him as just another man, who (as we all do in different ways) has an important part to play in God's plan and Church.

Most of us, as we mature, come to see our parents not simply as The Parent but as people, with strengths, weaknesses, foibles and motivations not so very unlike our own. Indeed, the Bible acknowledges as much and more when it enjoins the son (in Ecclesiastes, is it?) to respect his father and mock him not, even if in age his wits should fail him. Thus, it should perhaps not be surprising that as adults we sometimes find it harder to experience our priests as fathers in the sense that we remember our fathers from childhood -- full of stern wisdom and justice, loved, feared, but often not fully understood.

Monday, July 10, 2006

Uncommon Dissent

I can't say I'm particularly hurt, as one's blog is clearly one's own to do with as one wishes, but it does seem rather odd that a group whose mantra is "teach the controversy" has an official policy of designating commentors as "trusted" or "potential trouble" (which includes all those who don't fully accept ID theory), and holding the opposition comments for review before posting. They're also pretty clear that they ban people whom they are tired of hearing disagree with them -- indeed their editor was so kind as to tack threats of immanent ban onto most of my comments that did get through.

Nevertheless, it does give me a wonderfully dangerous feeling to have been designated as unsafe for the good believers over there. So if you see me swaggering around intoning "Arrrrr" and looking vaguelly piratical, you shall know why.

Bedside Manner

Even a cooling shower couldn't cut the heat. I emerged from the bathroom, towelling myself off, and then I saw it. Something large and leggy, perched upon the headboard of my very own bed. A roach. I gave an involutary shriek, and IT BEGAN TO FLY.

Darwin shoved me out of the room so my squeals would not further disturb the winged intruder or the sleeping baby (who, thank God, was in the cradle and not on the bed) and then retreated to the bathroom to finish brushing his teeth. I stood in the hall, shaken and wet and (having dropped my towel in the mad rush from the room) without a stitch on. Eleanor stood sleepily in her bedroom door.

"What are you doing, Mommy?" she asked.

"I'm just looking for clothes," I lied. She acknowledged this unquestioningly and went back to bed.

I sat on a bed in the girls' room, listening to the drama unfold in my bedroom. Shortly I heard a large crack and a steady mantra of profanity. A moment later, Darwin came out bearing the baby.

"The roach went behind the headboard," he said, "so I tried to shift the bed by the footboard so I could get behind it. And the bedframe broke. So I tried to pull it by the headboard. And it broke there too. And the roach has disappeared. So I brought you the baby so you two could settle down in here."

The thumps from the other room soon put Baby back to sleep, and my desire to get dressed was overcoming my dread of suddenly meeting the roach again, so I joined Darwin. Sure enough, there was the large wooden bed frame we'd bought a few weeks before our wedding, leaning drunkenly on a diagonal, the bottom right rail and the top left rail splintered off from their respective moorings. We spent the next hour disassembling the bed and cleaning underneath it (a monumental task) but the roach was nowhere to be found.

Finally the bedframe was packed away in the garage for future repair or reworking, the mattress and box-spring were laid on the floor grad-student style, and Darwin had searched under all the furniture with a flashlight. At that moment Eleanor once again appeared. She was oblivious to the disappearance of the major furnishing of our room.

"What is Daddy doing?" she asked. Daddy went into the bathroom and nudged the clothes pile on the floor and the roach flew up at him. There was a strangled cry and Darwin grabbed the first shoe to hand and slammed the door to do battle with the Thing.

"Daddy's killing a roach, honey."

Behind the closed door there were thwacks and battle yells and bangings, and then a suspenceful silence. Then Darwin flung open the door: flushed, triumphant, bearing his enemy in a plastic bag. A big brain confers evolutionary advantages over sheer ugliness.

So now the roach is vanquished, the window with the hole in the screen stays shut, and we have no bed. The girls still haven't noticed, but the room certainly looks cavernous without the comforting presence of the comfy bed. Perhaps it can be fixed. Perhaps the headboard and footboard can be bolted to one of those metal frames. Perhaps we'll have to buy a new bed, or perhaps our mattress and boxspring will remain on the floor, grad-student style.

Damn roach.

Saturday, July 08, 2006

Welcome GeneExpression Readers

A few recent posts on evolution are on the current main page. However, many more (pro evolution and contra creationism and ID) may be found in the evolution meta thread.

Friday, July 07, 2006

Islam and Evolution

Islam Online provides a fatwa on how Muslims should regard evolution.

A Muslim writer provides a different persective at the Guardian's online opinion outlet.

Re-reading Fellowship

Tolkien formally detested allegory, and so I think it's telling that the scenario he created is one that really isn't applicable to our own history. Though the standards of culture may vary, depending on the level of education and spirituality in a given historical setting, I would contend that there's never been a "golden age" from which we retreat in inexorable decline. There's no other species, or for that matter any particular race, that is somehow closer to creation and to the eternal verities and therefore setting impossibly high standards for art, literature, music, and architecture.

Different ages have different styles and priorities, yet I don't think anyone would hold that Stonehenge is somehow superior to a Gothic cathedral. Both a Gothic cathedral and the Empire State Building are the monumental architecture of their respective ages, yet both were built by men -- men whom we can study, understand, and aspire to equal. The cathedral, to my mind, surpasses the Empire State Building in terms of architectural transcendance and also in terms of sheer usefulness -- if we ever enter another dark age, the cathedral can still be used for its intended purpose while the State Building will stand empty with no lights or air conditioning to make it useable -- but that's simply because they were build for different purposes, not because one culture was superior to the other.

I'm not a member of the cult of Progress, but I don't ascribe to the Glorious, Irretrievable Past. No one age has a lock on truth, beauty and goodness. Mankind remains mankind, and that's why we're able to come to grips with the great ideas and glorious creations of men throughout the ages -- because we're all capable of participating in the eternal Now of God.

Thursday, July 06, 2006

The Amendment We Love to Hate

Here, of course, we see the other use to which the 18th amendment is consistently put: as a generic example of regulating something which clearly should not be regulated. Now, let me be clear, I think prohibition was a terrible idea, and it did lasting harm to our country both in giving support to criminal organizations that continue to exist to this day, and in destroying much of our native brewing heritage.

However, I think that writing off our country's misguided experiment with prohibition as "the zeal of certain Calvinists to ban alcohol" represents an excessive simplification which fails to do justice to the history involved.

The story of Prohibition really goes back a good hundred and fifty years before its ratification in 1919 (not coincidentally, only a year before the ratification of the 19th, giving women the right to vote). Gin was invented in the 1600s, and became wildly popular in Britain in

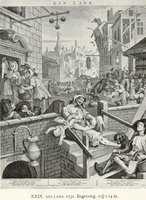

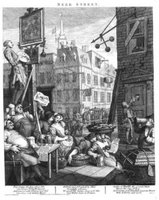

the mid seventeen hundreds. Gin was domestically produced, and thus not subject to import tariffs, it could be manufactured using grain that was too low quality for beer production, and thus it was incredibly cheap. This availability of cheap distilled spirits came at the same time as the tumultuous beginnings of urbanization and industrialization, and the result was that by 1740 gin production was six times that of beer, which given the relative strengths of the two drinks suggested obvious problems. Beer was a healthful drink (more so than water, since boiling killed bacteria and fermentation kept more from coming) while gin was a fast way to forget your troubles. William Hogarth's Gin Lane (left) and Beer Street

the mid seventeen hundreds. Gin was domestically produced, and thus not subject to import tariffs, it could be manufactured using grain that was too low quality for beer production, and thus it was incredibly cheap. This availability of cheap distilled spirits came at the same time as the tumultuous beginnings of urbanization and industrialization, and the result was that by 1740 gin production was six times that of beer, which given the relative strengths of the two drinks suggested obvious problems. Beer was a healthful drink (more so than water, since boiling killed bacteria and fermentation kept more from coming) while gin was a fast way to forget your troubles. William Hogarth's Gin Lane (left) and Beer Street  (right) engravings underscore moral reputation of each drink.

(right) engravings underscore moral reputation of each drink.As urban areas exploded in the late 1700s and throughout the 1800s both in Europe and in the fledgling United States, massive alcoholism (on a scale which can scarcely be imagined now) became a major social scourge in slums crammed with recent immigrants, those who had recently moved from the country into the city, the poor, and the unemployed. With gin (and whiskey and rum) soaked slums came crime, violence, and domestic abuse, not to mention chronic unemployment.

In response to all this, a temperance movement sprang up (you see some of this in Dickens, though he was by no means a supporter of complete tea tottling) which first sought to encourage temperance, and later began to push for total abstinence. There was certainly a religious element to this, but in some ways the religious argument against drinking was played up to support the social desire to cut down on drunkenness -- very few Protestants condemned all consumption of alcohol prior to 1700, and few enough had a problem with it as of 1800. Beer and wine especially were generally seen a innocent table drinks.

As a political force, the push to legally ban all alcohol in the United States grew alongside the other great 19th century progressive movements of abolitionism and women's suffrage. Temperance was in many ways seen as a women's issue, since spousal abuse often went along with excessive drink. And somewhere along the way the desire to ban alcohol separated from the need to do so. By the time the 18th amendment went into effect, after World War I, the gin alleys and oppressive slum conditions of the 1840s had vanished for mostly economic reasons. Poor neighborhoods were still desperately so by modern standards, and drinking was still chronic among some groups within those neighborhoods, but conditions were not anywhere near as bad as they had been eighty years before. Perhaps, to be cynical, it only became feasible to ban alcohol nationally because there was no longer such a massive problem with alcohol consumption.

Whatever the reason, prohibition was unquestionably a disaster.

Update on Jack

Jack is still in the hospital...the poor child has a bladder infection right now. They did the MRI which still shows clear on all those spots he had in May...yeah!!!! The one gray area they aren't sure about is smaller, so that is good news too. Monday they put a C-line in his chest in preparation for the next step. I will explain this as best I can, but I'm not sure that I have this right. They want to put him on a machine where they filter his blood for stem cells. This will take a day. If they can't get as many as they need this way, they will withdraw some of his bone marrow to get more (very painful, I hear). They will take his stemcells and grow them in the lab. Then they will kill off his bone marrow and put the stem cells back into his body. By doing this, they are hoping to trigger his brain fluid to produce more fluid, hopefully without cancer cells. I don't quite get this...but I do know that Jack will feel rotten during this and he will have to be in the hospital for at least 6 weeks. Right now, they think they will probably be doing this in August. They can use his own stem cells because this cancer rarely leaves the nervous system...so there should not be any cancer cells outside of his nervous system.This is all very hard on Jack's family, obviously -- please keep them in prayers as well.

Ten Questions for The Derb

Still, just as one is about to write The Derb off as not worth bothering about, you read something genuinely good he has written. The science blog Gene Expression published a Ten Questions For Derb interview that I ran across yesterday which is very much worth reading, and includes the following:

5) Over the years I've seen the following comment (in some form) multiple times: So and so is "perhaps the second most pessimistic opinion journalist right now, after John Derbyshire...." Do you think this characterization of you is accurate? Or do you think everyone else is just unduly optimistic?

Well, it depends what you mean by pessimism. I am a religious person, in a very general way -- I believe there is a supernatural realm accessible to our minds, and more real (in some way) than the natural world, which is really just a play of shadows. The fact that the natural world is a pretty nasty place therefore does not depress me as much as it ought. A nearby supernova could extinguish all life on earth in a few hours, sure -- but if you feel in your guts that there is another place beyond this one, then that isn't the end. Somehow. So on the grandest scale, I am not really a pessimist at all. On the everyday scale, though, I acknowledge that most of our nature, life, & experiences arise from the natural world & therefore partake of its general nastiness, coldness, cruelty, and gross unfairness. Civilized life fences off the horrors to some degree, which is why I am a huge fan of civilization (see above), but the fences are fragile, and the Old Adam will break through them sooner or later. Not in my lifetime, please.

Wednesday, July 05, 2006

Ending the Revolution

The 4th of July is the primary patriotic holiday of our country, and yet the event it commemorates (the publication of the Declaration of Independence) was just the first step on our road to nationhood. Although the Second Continental Congress ratified the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the Articles of Confederation were not adopted until November of 1777 and were not ratified until March of 1781 -- the year that the Revolutionary War was finally won, with the surrender of General Cornwallis in Yorktown. Yet the Articles turned out to be a fairly unworkable practical form of government, and Shay's Rebellion of 1786-1787 demonstrated that to many of the new country's citizens, armed revolt was still a standard form of political expression.

The ratification of the US Constitution in March of 1789 represented a significant step, creating a stronger central government with more clearly defined powers, and a model for federal constitutions to this day. Yet, whether the words on paper could be translated into a lasting and stable government remained yet to be seen.

To my mind, one of the major milestones was reached in 1794, when President Washington put down the Whiskey Rebellion.

The origins of the conflict rested in 1791, when the federal government, having assumed the states debts that had resulted from fighting the Revolutionary War, levied a tax on distilled spirits. In a move that was arguably quite unjust, the tax was $0.06/gal for large producers, but $0.08/gal for small producers, many of whom were small farmers in the far western areas of the 13 states for whom distilling grain into spirits was the only practical way to get their produce to market -- given the lack of transportation for getting grain to the eastern cities. The taxes stood a good change of putting many small farmers under, and loosely organized groups of revolutionaries first mounted protests, then began to rob the US Mail, disrupt federal courts, harass or attack tax collectors and even threatened to attack Pittsburgh, which was the westernmost big city in the area of the uprising.

On August 7th 1794, President Washington invoke the Militia Act to call up an army composed of state militias. He personally took command of this force of 13,000 along with Alexander Hamilton and General Henry Lee. With this force (nearly as large as the entire continental army during the Revolutionary War) they quickly supressed the revolt. Several ringleaders were sentenced to death for treason, but Washington pardoned them. Many of the small distillers moved out to Kentucky and Tennessee, which were essentially outside of federal jurisdiction, and settled down to become the most famous US distilling region. The tax on spirits was repealed in 1802.

In acting forcefully and bringing an end to trend towards local insurrections, Washington made it clear that politics, not armed rebellion would be the driving force in American history. In order for the rule of law to take root, the government must have a monopoly on organized military force -- lesson that the fledgling Palestinian state has yet to learn. The events of 1794 put our country well on the road to political stability and lasting peace.

Evolution in the Classroom

"I thought I was going crazy," said Ms. New, who has won several outstanding teacher awards and is one of only two teachers at her school with national board certification. The other is her husband, Ward.All other things aside, it seems to me that there's a value to knowing about a controversial topic like evolution, even if you don't yourself ascribe to it.