Dear Agent,

STILLWATER (145,000 words) is a character-driven, modern retelling of Jane Austen’s most controversial novel, Mansfield Park. Set in a historic plantation house in the sugarlands of Louisiana, this novel will appeal to readers searching for reimaginings of Austen such as Miss Austen by Gill Hornby, or Whit Stillman’s novel Love and Friendship. Even without reference to Austen, STILLWATER can be appreciated in its own right as literary fiction in the style of A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles.

Stillwater, owned by the Andrews family since before the Civil War, is the grandest surviving plantation house in Louisiana, and petite Cajun Melly Arceneaux its humblest resident. Painfully introverted, physically fragile, informally adopted by her benignly neglectful Andrews godparents, Melly prefers to linger in the shadows of her beloved Stillwater as a companion and drudge. As long as she can depend on the friendship of idealistic seminarian turned teacher Malcolm Andrews, and escape the notice of his worldly siblings and the ruthlessly efficient estate manager Esther Davis, she is content.

But when a pair of dazzlingly amoral siblings from New York City, Alys and Ian Winter, take a lease on one of Stillwater's old cottages, Melly finds her friendship with Malcolm, her secure home, and her integrity assailed from every side. The Winters, cheerfully ready to disrupt every aspect of life at Stillwater, discover to their fascination that Melly’s meekness can hide an astonishing reserve of fierce inner strength. And Melly will discover whether she has the courage not only to stand alone in her convictions, but to fight for Malcolm and for Stillwater at the risk of losing them forever.

I live in Ohio, and grew up making summer visits to my grandparents in their antebellum home near Baton Rouge. Theater is my first love, but reading classic literature aloud to my children is a close second.

Thank you for considering my novel, and I look forward to hearing from you.

Sincerely,

MrsDarwin

Saturday, May 23, 2020

Thursday, May 21, 2020

Understanding the COVID-19 Outbreak: Part 4

This is the fourth installment of this increasingly long series on the COVID-19 pandemic. You can read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 at these links. In this post, I'll assess the outbreak by the numbers and try to address the question of whether by those numbers the coronavirus can rightly be called a pandemic at all.

The Numbers

Various other commitments have slowed me down over the last few days, but I want to turn now to the question of numbers. As I discussed in Part 3, the definition of a pandemic is a disease that affects a large number of people throughout the world. One of the difficulties in assessing events as they happen is that we often know less about the present than we do about the past. With the past, we have the benefit of knowing where things are going, how the story ends, and we also have the time to gather information from many sources, the time to organize information and sift it. The coronavirus pandemic has been a blogger's and even more so a Tweeter's kind of news story. There are multiple online data sources which are posting data in what seems like nearly live time. You can go to the John Hopkinds University dashboard or the Worldometers coronavirus webpage or the Covid Tracking Project and see new statistics appearing every few minutes. The CDC and many states, counties, and even cities have set up their own data dashboards where they publish daily data. People representing important institutions have gone on TV and announced that they have built statistical models which can predict what will happen if various actions are taken and how the outbreak will progress. All of this gives an appearance of a situation where we know a great deal and can make the predictions with all the authority of techs crouched over computer screens and plotting the trajectory of a space capsule.

And yet, think for a moment about where all this seemingly abundant data comes from.

A disease is not a web stat or a stock market price or some other thing which is collected directly into a computer at the moment it happens. Someone gets sick. Maybe they take a test. Maybe they don't. If they do take a test, some amount of data may be collected about them: when did they get sick, how old are they, where have they been, who have they been near. Or it may not. That data may be collected to some central repository in a useful way, or it may not.

Someone dies. That person has been sick. Was it coronavirus? Was the person tested? How sick were they before? How old were they. When and where did they even die?

When people are massively overwhelmed with the difficulty of fighting a serious disease outbreak, they may get messier about collecting data. If they have almost no infections of a particular disease in the area, they may not think to test for it. Or they may try to test, but not have a good way to report the results.

The result of all this is that although we receive new data constantly, the data we have is at best a partial view of what is really going on out in the world, and the relationship between this partial view and the world itself is a matter of some dispute. Combine this with people who have decided to address the facts ideologically or who are determined to either minimize or maximize the pandemic in order to alleviate their particular emotional reactions to it, and there is a great deal of confusion out there.

I'll run through the basic numbers and to what extent we do or do not know them.

The number of people who now have or have in the past been infected by the SARS-CoV-2 virus: This number is hard to know with any certainty right now, because not all people who are sick are tested, sometimes the test provides a false negative result, and many people (though what percentage we don't know) are infected by the virus and are contagious but don't show any symptoms. Probably at some point in the future epidemiologists will have some sort of a backward looking estimate of the number, but even that will be based on assumptions we can't totally prove. This is no different from any other major disease. We do not, for instance, know with any great certainty how many people had the 1918 Spanish Flu, or how many people had AIDS or Ebola, etc.

The number of people who have tested positive for actively having COVID-19 (the disease caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2): This number is clearly reported and you can download the data from many sources. The only thing that is a little bit confusing is knowing when the person who tested positive first got the virus. There can be a lag of some days or even a couple weeks between when someone gets the virus and when they are tested and get a positive result. This means that the number of positive tests that are recorded on a given day can be a mix of people who contracted the virus up to a few weeks before and people who got it quite recently.

The number of people who have ever had the virus: This can be estimated with antibody tests, tests that analyze someone's blood and look for the antibodies that the body makes to fight off the SARS-CoV-2 virus. If someone has those antibodies, we can conclude that that person at some point contracted the virus. There have been a number of tests of this type conducted in different regions and with different sampling techniques. They have so far produced widely varying estimates of how many people have had the virus in different parts of the country. I think in the long run, major well run studies will establish this pretty clearly, but right now there are a lot of flaky, tiny studies out there, some of which are being run by people with agendas or with very poor methodologies.

The number of people who are hospitalized as a result of the virus: This number we know moderately well, so long as enough tests are available to test people who are under care because of symptoms which appear to be similar to the virus. However, here we run into reporting issues: not all hospitals have the time and resources to report on how many COVID-19 patients they have consistently, and not all cities and states are collecting and tabulating the data in the same way. This is something that in the long run will probably be known pretty well but which right now can be tricky to sort out clearly.

The number of people who have died as a result of the virus: You would think it would be pretty easy to know if people had died or not. Overall, I think number of deaths due to COVID-19 is probably one of the clearer measures that we have right now. However, even here we have the difficulty of diagnosis. If someone died after having been sick with symptoms that look like COVID-19, but that person has not been tested, whether they are classified as being a COVID-19 death will depend on the reporting agency tabulating the results. Some countries are also overwhelmed or do not have very good data gathering systems, and so their tabulations of deaths are simply not good. A few countries don't even keep accurate records of how many people die. And even in the US, although we have pretty meticulous data on deaths, our systems got gathering it are slow, as cities report to states and states report to the CDC. As a result, although through one system we have people reporting to the CDC very quickly how many people are dying of COVID-19, our data on how many people have died in total is partial for up to a couple months until all the data gathering and cleaning is done.

The percent of people who get the virus who die as a result: This number is trickier to get than you would think. Say you pull up a dashboard right at this moment and you see that the US has 1,573,073 cases of COVID-19 to date and 93,653 deaths. Simple division would tell you that 6% of cases result in death. This is called the Case Fatality Rate or CFR, and you'll hear that number thrown around. But as I discussed above, although we know how many people have tested positive for the coronavirus, we don't know how many people have actually had it. We can be pretty sure that we haven't tested very person who is sick. So the denominator of that fatality rate equation if we wanted to calculate the actual changes of someone dying due to the virus is some number bigger than 1.5 million. But how much bigger? If the number of people who have actually had the virus is five times larger, then the fatality rate is 1.2%. If it's ten times larger, then the fatality rate is 0.6%. If we've only tested 1 out of a hundred of the people who are actually sick, then the fatality rate is only 0.1% and is similar to the seasonal flu. But if we were to assume that the number of people actually sick is 100x the number of positive tests, we'd have to say that 157 million people have had the virus, almost half the US population. That seems very, very hard to believe, and it doesn't align with any of the serology tests I mentioned above. FFor instance, an antibody test in New York in late April found that about 25% of people in New York City (the area hit by far the hardest) had had the virus. Given the number of deaths New York City had experienced at the time, that would suggest an average fatality rate of around 0.5% or about 5x the fatality rate of the seasonal flu. (The Santa Clara study that the linked article also mentions has been widely questioned and should probably be ignored because most of the positive may have been false positives.)

All of this should make clear, there are a lot of things that we don't know when it comes to the numbers that surround the pandemic. What basic things can we draw from the available data? What things can we conclude are definitely not true?

We know that it is a serious disease which is capable of spreading through a significant percentage of the population and causing a large number of deaths. And we know that these deaths are not just expected deaths from flu or pneumonia that are being mis-categorized. Let's look at some New York data to validate this.

The first look is simple. Pulling data from the COVID-19 Project, I built a basic chart of New York State reported COVID-19 deaths by day with a 7-day moving average:

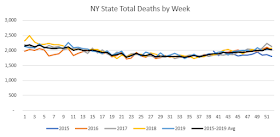

This seems pretty straight forward. It increases sharply near the beginning. Then it peaks and it goes down more slowly. There are a total of almost 23,000 deaths. And yet, some might ask, how do we know these are actually unexpected deaths? Lots of people die every day. Indeed, in the long run, 100% of people die. So how do we know these deaths aren't just like a "bad flu season" but being blown out of proportion by media frenzy and political passions? We can examine that question a bit on our own. The CDC has a data repository that allows us to look at weekly deaths due to flu, pneumonia, and total deaths by week either nationally or by state/region. I've downloaded the data for New York State. Here's data for total deaths and for flu/pneumonia since mid 2015:

As you can see, the trends are fairly predictable. 2016 was a pretty mild flu year. 2018 was a fairly bad one. But the lowest variance I see of any week's total deaths below the average is Week 6 (mid Feb) in 2016 which was 263 deaths below the average of 2,077. The highest variance was in Week 2 of 2018 when total deaths were 298 above the average of 2,195. Thus, each year's actual total deaths by week are within +/- 15% of the average.

Now let's look at this year.

Whereas the most variation we'd seen before was 15%, here we have two weeks that are more than 100% above the average. If I sum the total "excess deaths" (the space between the orange line representing this year and the black line representing the average) we get 8,251 deaths. That's actually significantly less than the reported New York State deaths to date, but the most recent weeks of this CDC death data are incomplete, and it doesn't even have weeks 20-21. As the year progresses, we'll able to see how this settles out, and we'll also see whether we see lower than average deaths through the rest of the year, which would support the claim some have made that many of these people would have died soon anyway. (I do not expect that's what we'll find.)

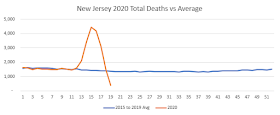

We see the same thing with other states we've been hearing about in the news. In New Jersey there are 10,147 excess deaths in the data thus far, with the top week 208% above the average.

In Michigan, 3,985 excess deaths thus far, with the top week 59% above the average.

These spikes in deaths are far, far outside anything that we've seen due to season flu. In New York State, the worst spike above average in the last five years was 298 deaths in Week 2 of 2018. Here we're seeing an effect which is more than seven times bigger than that. Indeed, the excess NY State deaths in April of 2020 look like they'll be at least 2x the number of excess deaths in September 2001.

So far, the coronavirus is an intensely regional problem. Some states have very bad outbreaks and some have very mild ones. Yet even so, the impact is measurable on a national level even though data is still far from complete for the last couple months.

I've done a couple things with this graph to try to make it readily understandable. (Click on it to get a larger image.) I've made the multi-year average a heavy black line, and this year is a heavy red line. Other years are in colors and are much thinner lines. However, I've made 2018 a medium thickness orange line, because the 2017-2018 flu season is an example of a particularly bad recent flu season. If I compare late 2017 and early 2018 to the national average, I come up with around 38,000 excess deaths from that flu season, with the worst weeks being 10% above the average. With the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020, I'm showing 50,000 excess deaths with the worst week being 30% above average. However, let me emphasize, the most recent weeks do not have complete data. You can see that with the way that the red line falls off the bottom of the graph in Week 19. That's not because no one died. It's because the CDC doesn't have complete data. It will continue to revise the most recent 10-13 rolling weeks as it moves forward, so we won't have a fully clear view of this April/May time period until August or September. (I fully intend to check back and provide more analysis at that point.)

Even so, you might ask yourself: Why are we shutting the country down? We did basically nothing to stop the 2017-2018 flu season, and we just accepted those "excess deaths" which are themselves in excess of season flu deaths that we suffer every year without shutting the economy down. So why are we doing this now? Is there something acceptable about 38,000 excess deaths that's totally unacceptable about 50,000?

The answer lies in the question. There's been an unprecedented effort to reduce the chances for this virus to spread since we as a country got serious about things in the middle of March. Apple provides a really interesting tool which allows you to see how much people's use of their Maps app to travel had gone down in various areas. Take a look:

All that reduction in moving around represents people going fewer places and spending less time around other people. And if we think back to the question of how a virus spreads, it's all a mathematical function of how easily it is spread from one person to another, and how many other people a sick person comes in contact with. If you have a one in 50 chance of passing the virus to each person you interact with during a two week period of being contagious, then it matters a lot whether you come in contact with 10 people or 200 people during that two week period.

Having spent so much time discussing the virus online over the last few weeks, I can already hear someone saying, "What about Sweden? They haven't shut down, and they're doing okay." Well, okay is relative. They're hit much harder than the other Scandinavian countries in terms of deaths so far. But more importantly, just because they haven't had a legal "lockdown" doesn't mean that they aren't circulating a lot less. Here's the same movement graph for Sweden.

So Swedes actually are staying home a lot more, and in particular they're using public transit 33% less than they were before. And as a result, their economy is seeing a lot of the same slowdown that we are.

So while it's true that so far (and there's a lot of emphasis in that "so far" because our data isn't nearly complete yet) the number of excess deaths we can measure is less than twice that of a bad though normal flu season, that's within the context of an outbreak which we've put the brakes on by having everyone hunker down. And even as people now begin to return to more normal activities, they're doing so with a much greater than normal awareness of avoiding behavior that might pass on a respiratory virus. In that sense, it would seem likely that the virus is spreading significantly more slowly now than in a "do nothing" scenario such as our normal response to flu season. If we were going to try to say whether our response to the risk of the virus was proportional to the danger we faced, we need to look not at what's actually happened (which is 90,000 deaths according to the official tally and 50,000 according to the far-from-complete "excess death" analysis) but rather try to get some sense of what could have happened if we had not acted to drastically slow the spread of the virus.

Let's try a basic range of assumptions that seem within the realm of possibility. We know that there are 330,000,000 people in the US. Say that the ~25% infection rate for New York City which is suggested by antibody tests is actually the outer bound of how many infections a region could have before it peters out due to not having enough non-immune hosts left available. (For comparison, estimates are that it was about 25% of the US population that got Spanish Flu back in 1918 as well.) And say that the 0.5% infection fatality rate that suggests given New York City's death numbers is also correct. 330M times 25% times 0.5% is 412,000 deaths. Let's take that as our low number. For a mid number, let's assume that NYC is actually not at the maximum saturation point for infections. Maybe if we pretty much went about our normal lives about 40% of the population would get the virus. If we assume 40% infections and 0.5% mortality, we get 660,000 deaths. For our worst case scenario, let's imagine a 40% infection rate but also that the fatality rate that I'm estimating is a bit low. What if it's more like 1%, which I think is about the upper bound of the reasonable infection fatality rates that I've seen. Those assumptions get us to 1,320,000 deaths.

So if we hadn't done all this to try to stop the spread of the virus, there's a pretty decent possibility that we would be facing 400k to 1.3M deaths. I think we could all agree that's a really large number, and one it would be reasonable to take some pretty drastic actions to avoid. If the actions we're taking can reduce those down to something in the 100k to 200k range, it seems like that would be a potentially reasonable course of action. (I want to examine in depth the question of whether "lockdowns" actually save lives or just space them out over more time, but I think that needs its own post.)

However, a counter-argument that is often made is that while COVID-19 causes a lot of deaths, those are actually deaths that would have occurred soon anyway. According to this argument, the virus is mostly killing people who are very old and/or have existing conditions that put them in fragile health.

This is to some extent true. Here's a shot of the COVID-19 dashboard for my state of Ohio. I think it does a really good job of showing the dynamics of the virus:

Note that while actual cases are spread pretty evenly across the whole population, with the exception of kids, more than half of the 1,836 deaths were among people who were 80+.

So what does this mean in terms of the actual chance that people with COVID-19 will end up in the hospital or will end up dead? As we discussed earlier, lots of people who have the virus have not actually been tested, so the case numbers don't tell us everything. I also said that 0.5% overall fatality rate for all infections (not just identified cases) seems like a pretty plausible number based on the antibody studies from New York City. So here I've taken the Ohio population, assumed that actual infections are evenly distributed across the population even though the very mild nature of the disease in younger people means that fewer cases have been identified among the younger age groups, and projected an estimated total number of infections based on a total population IFR of 0.5%. (In other words, I first calculated that there were 367,200 infections by assuming that the 1,836 deaths represented a 0.5% IFR, and then spread those infections across the age groups based on the percent of Ohio residents in each age group.)

Having done that, I calculated what the hospitalization rate was for each age group. The answer? For people who are 80%, 6.4% of estimated infections were fatal. For people in their 20s, only 0.01% were fatal. Hospitalization rates are a bit higher. There's a 1.2% chance for someone in their 40s who gets the virus having a bad enough case to end up in the hospital. But the rates are still overall low. Indeed, so low that you may be thinking: Why worry? This looks like nothing!

Well, for a lot of people the virus does give no symptoms at all or very mild symptoms. But keep in mind, we have a lot of people in our country. There are 12.5M people over 80 in the US. Apply these rates across the whole US population and you get to some large numbers. Let's go back to our minimum scenario where 25% of the US population got the virus. What would these hospitalization rates and fatality rates mean in terms of total deaths for different age groups? What I've done here is calculated 25% of the US population as the total number of infections and then distributed those infections evenly across the population according to how many people are in each age group. Obviously, there are a lot of assumptions being made here, but as a conservative scenario I don't think it's unreasonable.

How do we think about this? 400,000 Americans dead is a lot of people. Three quarters of them would be seventy or over, but there are plenty of people who are seventy years old who have ten or twenty good years of life before them. Does this call for the kind of massive actions that we've taken or not? How do we think about the 10% of Americans who would be suffering 75% of the deaths? I'm not going to say that that's a super easy question. And of course, these are only rough estimates made based on multiple assumptions. We had less data when we were making the decisions that put us into this position back in March -- though we did have a fair amount of the data. I want to dig more deeply into the question of the "lockdowns" in the next post, but before I do that I'd like to point out that we often get too locked into talking about deaths only. Death is coming for all of us, and yet we don't want to die early, nor do we want to see our loved ones do so.

But as we think about how much people would want to avoid getting this disease, how much they would stay away from restaurants and big gatherings in order to stay healthy even if not ordered to, and slow down the consumer economy as they did so, it's worth looking at the other set of estimates. Someone in his forties is almost a hundred times less likely to die if infected with the virus as someone who is 80+, but he's still a sixth as likely to end up in the hospital. While my estimate is that if 25% of Americans got the coronavirus, only 90,000 people under 70 would die of it, over 700,000 people under 70 would spend time in the hospital. Indeed, while 75% of the deaths would be people over 70, more than 60% the people hospitalized would be people under 70. 20% of the people hospitalized would be under fifty. 10% of people hospitalized would be under forty. I think we have to assume that there would be lots of other people who never ended up in hospitals but who felt really, really sick and scared for a couple weeks as they waited to see if they'd end up having to go to the hospital.

There are a lot of things that we don't know about this virus, and there are a lot of things we can reasonably argue about in how to respond to it. However, I think that this examination of the numbers underlines that while there have definitely been panicked numbers thrown around by people who didn't know what they were doing (I don't think that claims we'd see 5-10 million deaths ever fit well with what we knew, even back in February) this is a serious disease which, if left unchecked, could be responsible for a lot of deaths and a great deal of suffering. Hopefully this provides some insight into just what the dimensions of those possibilities are (and aren't.)

In my next post, I'll talk about the measures that have been taken to suppress the virus, including the "lockdowns" which are the subject of so much political dispute.

The Numbers

Various other commitments have slowed me down over the last few days, but I want to turn now to the question of numbers. As I discussed in Part 3, the definition of a pandemic is a disease that affects a large number of people throughout the world. One of the difficulties in assessing events as they happen is that we often know less about the present than we do about the past. With the past, we have the benefit of knowing where things are going, how the story ends, and we also have the time to gather information from many sources, the time to organize information and sift it. The coronavirus pandemic has been a blogger's and even more so a Tweeter's kind of news story. There are multiple online data sources which are posting data in what seems like nearly live time. You can go to the John Hopkinds University dashboard or the Worldometers coronavirus webpage or the Covid Tracking Project and see new statistics appearing every few minutes. The CDC and many states, counties, and even cities have set up their own data dashboards where they publish daily data. People representing important institutions have gone on TV and announced that they have built statistical models which can predict what will happen if various actions are taken and how the outbreak will progress. All of this gives an appearance of a situation where we know a great deal and can make the predictions with all the authority of techs crouched over computer screens and plotting the trajectory of a space capsule.

And yet, think for a moment about where all this seemingly abundant data comes from.

A disease is not a web stat or a stock market price or some other thing which is collected directly into a computer at the moment it happens. Someone gets sick. Maybe they take a test. Maybe they don't. If they do take a test, some amount of data may be collected about them: when did they get sick, how old are they, where have they been, who have they been near. Or it may not. That data may be collected to some central repository in a useful way, or it may not.

Someone dies. That person has been sick. Was it coronavirus? Was the person tested? How sick were they before? How old were they. When and where did they even die?

When people are massively overwhelmed with the difficulty of fighting a serious disease outbreak, they may get messier about collecting data. If they have almost no infections of a particular disease in the area, they may not think to test for it. Or they may try to test, but not have a good way to report the results.

The result of all this is that although we receive new data constantly, the data we have is at best a partial view of what is really going on out in the world, and the relationship between this partial view and the world itself is a matter of some dispute. Combine this with people who have decided to address the facts ideologically or who are determined to either minimize or maximize the pandemic in order to alleviate their particular emotional reactions to it, and there is a great deal of confusion out there.

I'll run through the basic numbers and to what extent we do or do not know them.

The number of people who now have or have in the past been infected by the SARS-CoV-2 virus: This number is hard to know with any certainty right now, because not all people who are sick are tested, sometimes the test provides a false negative result, and many people (though what percentage we don't know) are infected by the virus and are contagious but don't show any symptoms. Probably at some point in the future epidemiologists will have some sort of a backward looking estimate of the number, but even that will be based on assumptions we can't totally prove. This is no different from any other major disease. We do not, for instance, know with any great certainty how many people had the 1918 Spanish Flu, or how many people had AIDS or Ebola, etc.

The number of people who have tested positive for actively having COVID-19 (the disease caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2): This number is clearly reported and you can download the data from many sources. The only thing that is a little bit confusing is knowing when the person who tested positive first got the virus. There can be a lag of some days or even a couple weeks between when someone gets the virus and when they are tested and get a positive result. This means that the number of positive tests that are recorded on a given day can be a mix of people who contracted the virus up to a few weeks before and people who got it quite recently.

The number of people who have ever had the virus: This can be estimated with antibody tests, tests that analyze someone's blood and look for the antibodies that the body makes to fight off the SARS-CoV-2 virus. If someone has those antibodies, we can conclude that that person at some point contracted the virus. There have been a number of tests of this type conducted in different regions and with different sampling techniques. They have so far produced widely varying estimates of how many people have had the virus in different parts of the country. I think in the long run, major well run studies will establish this pretty clearly, but right now there are a lot of flaky, tiny studies out there, some of which are being run by people with agendas or with very poor methodologies.

The number of people who are hospitalized as a result of the virus: This number we know moderately well, so long as enough tests are available to test people who are under care because of symptoms which appear to be similar to the virus. However, here we run into reporting issues: not all hospitals have the time and resources to report on how many COVID-19 patients they have consistently, and not all cities and states are collecting and tabulating the data in the same way. This is something that in the long run will probably be known pretty well but which right now can be tricky to sort out clearly.

The number of people who have died as a result of the virus: You would think it would be pretty easy to know if people had died or not. Overall, I think number of deaths due to COVID-19 is probably one of the clearer measures that we have right now. However, even here we have the difficulty of diagnosis. If someone died after having been sick with symptoms that look like COVID-19, but that person has not been tested, whether they are classified as being a COVID-19 death will depend on the reporting agency tabulating the results. Some countries are also overwhelmed or do not have very good data gathering systems, and so their tabulations of deaths are simply not good. A few countries don't even keep accurate records of how many people die. And even in the US, although we have pretty meticulous data on deaths, our systems got gathering it are slow, as cities report to states and states report to the CDC. As a result, although through one system we have people reporting to the CDC very quickly how many people are dying of COVID-19, our data on how many people have died in total is partial for up to a couple months until all the data gathering and cleaning is done.

The percent of people who get the virus who die as a result: This number is trickier to get than you would think. Say you pull up a dashboard right at this moment and you see that the US has 1,573,073 cases of COVID-19 to date and 93,653 deaths. Simple division would tell you that 6% of cases result in death. This is called the Case Fatality Rate or CFR, and you'll hear that number thrown around. But as I discussed above, although we know how many people have tested positive for the coronavirus, we don't know how many people have actually had it. We can be pretty sure that we haven't tested very person who is sick. So the denominator of that fatality rate equation if we wanted to calculate the actual changes of someone dying due to the virus is some number bigger than 1.5 million. But how much bigger? If the number of people who have actually had the virus is five times larger, then the fatality rate is 1.2%. If it's ten times larger, then the fatality rate is 0.6%. If we've only tested 1 out of a hundred of the people who are actually sick, then the fatality rate is only 0.1% and is similar to the seasonal flu. But if we were to assume that the number of people actually sick is 100x the number of positive tests, we'd have to say that 157 million people have had the virus, almost half the US population. That seems very, very hard to believe, and it doesn't align with any of the serology tests I mentioned above. FFor instance, an antibody test in New York in late April found that about 25% of people in New York City (the area hit by far the hardest) had had the virus. Given the number of deaths New York City had experienced at the time, that would suggest an average fatality rate of around 0.5% or about 5x the fatality rate of the seasonal flu. (The Santa Clara study that the linked article also mentions has been widely questioned and should probably be ignored because most of the positive may have been false positives.)

All of this should make clear, there are a lot of things that we don't know when it comes to the numbers that surround the pandemic. What basic things can we draw from the available data? What things can we conclude are definitely not true?

We know that it is a serious disease which is capable of spreading through a significant percentage of the population and causing a large number of deaths. And we know that these deaths are not just expected deaths from flu or pneumonia that are being mis-categorized. Let's look at some New York data to validate this.

The first look is simple. Pulling data from the COVID-19 Project, I built a basic chart of New York State reported COVID-19 deaths by day with a 7-day moving average:

This seems pretty straight forward. It increases sharply near the beginning. Then it peaks and it goes down more slowly. There are a total of almost 23,000 deaths. And yet, some might ask, how do we know these are actually unexpected deaths? Lots of people die every day. Indeed, in the long run, 100% of people die. So how do we know these deaths aren't just like a "bad flu season" but being blown out of proportion by media frenzy and political passions? We can examine that question a bit on our own. The CDC has a data repository that allows us to look at weekly deaths due to flu, pneumonia, and total deaths by week either nationally or by state/region. I've downloaded the data for New York State. Here's data for total deaths and for flu/pneumonia since mid 2015:

As you can see, the trends are fairly predictable. 2016 was a pretty mild flu year. 2018 was a fairly bad one. But the lowest variance I see of any week's total deaths below the average is Week 6 (mid Feb) in 2016 which was 263 deaths below the average of 2,077. The highest variance was in Week 2 of 2018 when total deaths were 298 above the average of 2,195. Thus, each year's actual total deaths by week are within +/- 15% of the average.

Now let's look at this year.

Whereas the most variation we'd seen before was 15%, here we have two weeks that are more than 100% above the average. If I sum the total "excess deaths" (the space between the orange line representing this year and the black line representing the average) we get 8,251 deaths. That's actually significantly less than the reported New York State deaths to date, but the most recent weeks of this CDC death data are incomplete, and it doesn't even have weeks 20-21. As the year progresses, we'll able to see how this settles out, and we'll also see whether we see lower than average deaths through the rest of the year, which would support the claim some have made that many of these people would have died soon anyway. (I do not expect that's what we'll find.)

We see the same thing with other states we've been hearing about in the news. In New Jersey there are 10,147 excess deaths in the data thus far, with the top week 208% above the average.

In Michigan, 3,985 excess deaths thus far, with the top week 59% above the average.

These spikes in deaths are far, far outside anything that we've seen due to season flu. In New York State, the worst spike above average in the last five years was 298 deaths in Week 2 of 2018. Here we're seeing an effect which is more than seven times bigger than that. Indeed, the excess NY State deaths in April of 2020 look like they'll be at least 2x the number of excess deaths in September 2001.

So far, the coronavirus is an intensely regional problem. Some states have very bad outbreaks and some have very mild ones. Yet even so, the impact is measurable on a national level even though data is still far from complete for the last couple months.

I've done a couple things with this graph to try to make it readily understandable. (Click on it to get a larger image.) I've made the multi-year average a heavy black line, and this year is a heavy red line. Other years are in colors and are much thinner lines. However, I've made 2018 a medium thickness orange line, because the 2017-2018 flu season is an example of a particularly bad recent flu season. If I compare late 2017 and early 2018 to the national average, I come up with around 38,000 excess deaths from that flu season, with the worst weeks being 10% above the average. With the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020, I'm showing 50,000 excess deaths with the worst week being 30% above average. However, let me emphasize, the most recent weeks do not have complete data. You can see that with the way that the red line falls off the bottom of the graph in Week 19. That's not because no one died. It's because the CDC doesn't have complete data. It will continue to revise the most recent 10-13 rolling weeks as it moves forward, so we won't have a fully clear view of this April/May time period until August or September. (I fully intend to check back and provide more analysis at that point.)

Even so, you might ask yourself: Why are we shutting the country down? We did basically nothing to stop the 2017-2018 flu season, and we just accepted those "excess deaths" which are themselves in excess of season flu deaths that we suffer every year without shutting the economy down. So why are we doing this now? Is there something acceptable about 38,000 excess deaths that's totally unacceptable about 50,000?

The answer lies in the question. There's been an unprecedented effort to reduce the chances for this virus to spread since we as a country got serious about things in the middle of March. Apple provides a really interesting tool which allows you to see how much people's use of their Maps app to travel had gone down in various areas. Take a look:

All that reduction in moving around represents people going fewer places and spending less time around other people. And if we think back to the question of how a virus spreads, it's all a mathematical function of how easily it is spread from one person to another, and how many other people a sick person comes in contact with. If you have a one in 50 chance of passing the virus to each person you interact with during a two week period of being contagious, then it matters a lot whether you come in contact with 10 people or 200 people during that two week period.

Having spent so much time discussing the virus online over the last few weeks, I can already hear someone saying, "What about Sweden? They haven't shut down, and they're doing okay." Well, okay is relative. They're hit much harder than the other Scandinavian countries in terms of deaths so far. But more importantly, just because they haven't had a legal "lockdown" doesn't mean that they aren't circulating a lot less. Here's the same movement graph for Sweden.

So Swedes actually are staying home a lot more, and in particular they're using public transit 33% less than they were before. And as a result, their economy is seeing a lot of the same slowdown that we are.

So while it's true that so far (and there's a lot of emphasis in that "so far" because our data isn't nearly complete yet) the number of excess deaths we can measure is less than twice that of a bad though normal flu season, that's within the context of an outbreak which we've put the brakes on by having everyone hunker down. And even as people now begin to return to more normal activities, they're doing so with a much greater than normal awareness of avoiding behavior that might pass on a respiratory virus. In that sense, it would seem likely that the virus is spreading significantly more slowly now than in a "do nothing" scenario such as our normal response to flu season. If we were going to try to say whether our response to the risk of the virus was proportional to the danger we faced, we need to look not at what's actually happened (which is 90,000 deaths according to the official tally and 50,000 according to the far-from-complete "excess death" analysis) but rather try to get some sense of what could have happened if we had not acted to drastically slow the spread of the virus.

Let's try a basic range of assumptions that seem within the realm of possibility. We know that there are 330,000,000 people in the US. Say that the ~25% infection rate for New York City which is suggested by antibody tests is actually the outer bound of how many infections a region could have before it peters out due to not having enough non-immune hosts left available. (For comparison, estimates are that it was about 25% of the US population that got Spanish Flu back in 1918 as well.) And say that the 0.5% infection fatality rate that suggests given New York City's death numbers is also correct. 330M times 25% times 0.5% is 412,000 deaths. Let's take that as our low number. For a mid number, let's assume that NYC is actually not at the maximum saturation point for infections. Maybe if we pretty much went about our normal lives about 40% of the population would get the virus. If we assume 40% infections and 0.5% mortality, we get 660,000 deaths. For our worst case scenario, let's imagine a 40% infection rate but also that the fatality rate that I'm estimating is a bit low. What if it's more like 1%, which I think is about the upper bound of the reasonable infection fatality rates that I've seen. Those assumptions get us to 1,320,000 deaths.

So if we hadn't done all this to try to stop the spread of the virus, there's a pretty decent possibility that we would be facing 400k to 1.3M deaths. I think we could all agree that's a really large number, and one it would be reasonable to take some pretty drastic actions to avoid. If the actions we're taking can reduce those down to something in the 100k to 200k range, it seems like that would be a potentially reasonable course of action. (I want to examine in depth the question of whether "lockdowns" actually save lives or just space them out over more time, but I think that needs its own post.)

However, a counter-argument that is often made is that while COVID-19 causes a lot of deaths, those are actually deaths that would have occurred soon anyway. According to this argument, the virus is mostly killing people who are very old and/or have existing conditions that put them in fragile health.

This is to some extent true. Here's a shot of the COVID-19 dashboard for my state of Ohio. I think it does a really good job of showing the dynamics of the virus:

Note that while actual cases are spread pretty evenly across the whole population, with the exception of kids, more than half of the 1,836 deaths were among people who were 80+.

So what does this mean in terms of the actual chance that people with COVID-19 will end up in the hospital or will end up dead? As we discussed earlier, lots of people who have the virus have not actually been tested, so the case numbers don't tell us everything. I also said that 0.5% overall fatality rate for all infections (not just identified cases) seems like a pretty plausible number based on the antibody studies from New York City. So here I've taken the Ohio population, assumed that actual infections are evenly distributed across the population even though the very mild nature of the disease in younger people means that fewer cases have been identified among the younger age groups, and projected an estimated total number of infections based on a total population IFR of 0.5%. (In other words, I first calculated that there were 367,200 infections by assuming that the 1,836 deaths represented a 0.5% IFR, and then spread those infections across the age groups based on the percent of Ohio residents in each age group.)

Having done that, I calculated what the hospitalization rate was for each age group. The answer? For people who are 80%, 6.4% of estimated infections were fatal. For people in their 20s, only 0.01% were fatal. Hospitalization rates are a bit higher. There's a 1.2% chance for someone in their 40s who gets the virus having a bad enough case to end up in the hospital. But the rates are still overall low. Indeed, so low that you may be thinking: Why worry? This looks like nothing!

Well, for a lot of people the virus does give no symptoms at all or very mild symptoms. But keep in mind, we have a lot of people in our country. There are 12.5M people over 80 in the US. Apply these rates across the whole US population and you get to some large numbers. Let's go back to our minimum scenario where 25% of the US population got the virus. What would these hospitalization rates and fatality rates mean in terms of total deaths for different age groups? What I've done here is calculated 25% of the US population as the total number of infections and then distributed those infections evenly across the population according to how many people are in each age group. Obviously, there are a lot of assumptions being made here, but as a conservative scenario I don't think it's unreasonable.

How do we think about this? 400,000 Americans dead is a lot of people. Three quarters of them would be seventy or over, but there are plenty of people who are seventy years old who have ten or twenty good years of life before them. Does this call for the kind of massive actions that we've taken or not? How do we think about the 10% of Americans who would be suffering 75% of the deaths? I'm not going to say that that's a super easy question. And of course, these are only rough estimates made based on multiple assumptions. We had less data when we were making the decisions that put us into this position back in March -- though we did have a fair amount of the data. I want to dig more deeply into the question of the "lockdowns" in the next post, but before I do that I'd like to point out that we often get too locked into talking about deaths only. Death is coming for all of us, and yet we don't want to die early, nor do we want to see our loved ones do so.

But as we think about how much people would want to avoid getting this disease, how much they would stay away from restaurants and big gatherings in order to stay healthy even if not ordered to, and slow down the consumer economy as they did so, it's worth looking at the other set of estimates. Someone in his forties is almost a hundred times less likely to die if infected with the virus as someone who is 80+, but he's still a sixth as likely to end up in the hospital. While my estimate is that if 25% of Americans got the coronavirus, only 90,000 people under 70 would die of it, over 700,000 people under 70 would spend time in the hospital. Indeed, while 75% of the deaths would be people over 70, more than 60% the people hospitalized would be people under 70. 20% of the people hospitalized would be under fifty. 10% of people hospitalized would be under forty. I think we have to assume that there would be lots of other people who never ended up in hospitals but who felt really, really sick and scared for a couple weeks as they waited to see if they'd end up having to go to the hospital.

There are a lot of things that we don't know about this virus, and there are a lot of things we can reasonably argue about in how to respond to it. However, I think that this examination of the numbers underlines that while there have definitely been panicked numbers thrown around by people who didn't know what they were doing (I don't think that claims we'd see 5-10 million deaths ever fit well with what we knew, even back in February) this is a serious disease which, if left unchecked, could be responsible for a lot of deaths and a great deal of suffering. Hopefully this provides some insight into just what the dimensions of those possibilities are (and aren't.)

In my next post, I'll talk about the measures that have been taken to suppress the virus, including the "lockdowns" which are the subject of so much political dispute.

Saturday, May 16, 2020

Understanding the COVID-19 Outbreak: Part 3

This is the third part in a series. You can find the first part here and the second part here.

What Is A Pandemic Anyway?

My father-in-law tells a story about the day in high school that the football coach had to take over teaching Earth Science. He went up to the chalk board and began to write definitions. First up. "Lava flow" He considered a moment, then wrote the definition "Flow of lava".

I had a similarly recursive feeling when trying to look up definitions of "epidemic" and "pandemic" a while back in order to address the question of whether the coronavirus was really a pandemic. What is an epidemic? A disease that affects a large number of people in a region. What's a pandemic? An epidemic that spreads throughout the world. The CDC expresses it most succinctly of all: "A pandemic is a global outbreak of disease."

And yet words like "pandemic" and "epidemic" and "plague" carry a set of implications that cause many people to engage their mental yardsticks. I've heard many people express sentiments to the effect of, "If this is a real pandemic, why aren't the bodies piling up like in the Black Death?" The Black Death is a sort of core myth of Western culture at this point for epidemic, complete with the Monty Python image of people trundling along with carts calling "Bring out your dead!" It's a terrible, terrible disease (which is still out there and occurs in about 5,000 people a year globally, though it can now be treated with anti-biotics) but it is only one of a huge number of infectious diseases which used to account for the majority of human deaths.

If you look up the leading causes of death in the US at this time in history, you get the following list:

Influenza and Pneumonia topped the list, followed by Tuberculosis. All infectious diseases of different sorts. Why is influenza less of a killer now? For the same reason that tuberculosis and pneumonia are, to an extent. The influenza virus is not always the primary killer. Often it weakens the body and immune system which allows bacterial pneumonia to take over and finish the patient off. With modern antibiotics we can treat those bacterial pneumonias thus lessening the death rate of influenza. Additionally, we have the influenza vaccines which build the body's resistance to the virus strains themselves and we have antiviral medications which can help to some extent.

But influenza and other infectious diseases were fully capable of killing lots of people, and that was just in a normal time when there wasn't an epidemic on the loose.

What makes an epidemic different from run of the mill "endemic" disease? It's not necessarily that that disease is spectacularly deadly. A disease is epidemic when it is spreading through the population rapidly and infecting a large number of them. In theory this could happen with some fairly minor disease, so long as it was quite contagious and not many people have antibodies that protected them from it. The difference is just that if a minor sniffle spread rapidly through the whole population, we wouldn't notice it a great deal.

The point about people not having antibodies that protect them from the disease is key. Diseases are, after all, essentially parasites. A virus can't reproduce all on its own. It needs to take over the cell of another creature and commandeer that cell to manufacture copies of itself. Once the body recognizes a virus for what it is, a hostile invader, the body develops antibodies that destroy the virus. So imagine that I have a virus that's colonized my body and is using my cells to crank out copies of itself. I'm coughing out micro-droplets of water vapor which contain those viruses. But all the people I come in contact with are people who have already come in contact with that type of virus, and as soon as one of the viruses comes into one of these bodies, the antibodies destroy it. So even though the viruses that have taken over my body are cranking out copies of themselves, they can't successfully colonize any other bodies. After a couple weeks, my body too develops good enough defenses to start attacking the virus, and so my body wipes out the infestation of viruses in my body and it's the end of the line for that strain of viruses because they weren't able to colonize the bodies of any other people I came into contact with.

With an endemic virus, a common virus that's been around for a while in the population, a lot of the people the virus comes in contact with are already able to fight the virus off, and so spread is slow. We can see how that is important when we look at times when endemic diseases became epidemic diseases because they came in contact with a new population. After Europeans reached the new world, diseases that were common in Europe (measles, smallpox, influenza, etc.) but which had not before been present in the Americas suddenly turned into epidemics. Measles was not an epidemic disease in Europe. It has highly contagious, but lots of people had had it before and were immune. Even children who hadn't had it before received some antibodies from their mothers during pregnancy and nursing, giving their bodies a head start when they encountered the virus for the first time. But in the Americas, measles was totally unknown. The result was that what in Europe was a bad but survivable childhood disease became in the Americas a population decimating epidemic. Much the same happened with other diseases that had been common in Europe but not in the Americas.

That there were so many diseases that were common in Europe but not in the Americas is believed to be due to the fact that Europeans had domesticated many more animals and lived in close contact with them. Many viruses first jump to the human population via a mutation of some animal virus. For instance, the flu virus which caused the deadly 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic is believed to have jumped from swine to humans in Kansas in the spring of 1918. If you want to read lots of interesting discussion about virus mutation, immunities, and pandemics, I'd recommend John Barry's The Great Influenza which I've been reading and finding fascinating.

When a new strain of an existing family of viruses (such as the 1918 Spanish Flu strain of the influenza virus) appears via mutation and/or jumping from some animal species to humans, if it is different enough from other strains that the immune system does not recognize it, the virus can spread rapidly in much the way that these new diseases did in the new world. But even the case of a "novel" virus (such as the novel coronavirus that we're dealing with now) there can still be degrees of susceptibility. The 1918 influenza pandemic was a novel strain which was significantly more deadly than normal seasonal flu. Seasonal flu kills around 0.1% of those who get it. In 1918, the fatality rate was more like 2.5%, twenty-five times higher than "normal" flu strains. Moreover, while seasonal influenza mostly kills those we'd think of as medically fragile (infants and old/infirm people) the 1918 flu hit people in their 20s and 30s particularly hard. And while all lives are of equal worth, it's not unreasonable that people would consider particularly tragic a disease which suddenly cuts down healthy young people who appeared to have their whole lives before them. But that 2.5% fatality rate was not consistent everywhere. The fatality rate was much higher among isolated populations that had seldom been exposed to other strains of flu. For instance, Inuit villages in Alaska and Canada in many cases experienced much higher death rates, sometimes near 100%. The same was the case for Pacific Islander populations, Australian Aborigines, etc. It's believed that the reason for this is that populations which had experienced fewer outbreaks of other flu stains were even more defenseless against the virus that populations where people's immune systems had at least identified and fought off other flu strains. Even though this particular stain was novel enough that everyone was susceptible to it, the familiarity with other flu strains somehow gave the immune system enough of an edge that it was able to build its defenses more quickly.

Although SARS-CoV-2 is a "novel virus", it may be that exposure to other types of corona viruses is one of the things which causes some people to suffer little or not sickness from the virus, developing antibodies that can fight off the virus without the body suffering much of any damage first, while other people experience a long, difficult, or even fatal respiratory disease.

So is COVID-19 a pandemic? Well, it is a rapid outbreak of a disease which has spread across the world. It first appeared in China and has now infected significant numbers of people in Iran, throughout Europe, the US, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Ecuador, Turkey, Israel, India, the list goes on.

But as I said earlier, we could imagine a situation in which a disease was new enough that it swept across the world but in which the disease was not really that serious. What are we to say to the people who argue that COVID-19 isn't really killing many people, perhaps no more than an ordinary flu season?

I'd meant to get into the numbers question in this installment, but talking about the nature of pandemics took me longer than expected so I'll address numbers in the next installment, and at I'll also include a section of a the closely related topics: "lockdowns" and whether they have slowed the virus at all.

Click here for Part 4.

What Is A Pandemic Anyway?

My father-in-law tells a story about the day in high school that the football coach had to take over teaching Earth Science. He went up to the chalk board and began to write definitions. First up. "Lava flow" He considered a moment, then wrote the definition "Flow of lava".

I had a similarly recursive feeling when trying to look up definitions of "epidemic" and "pandemic" a while back in order to address the question of whether the coronavirus was really a pandemic. What is an epidemic? A disease that affects a large number of people in a region. What's a pandemic? An epidemic that spreads throughout the world. The CDC expresses it most succinctly of all: "A pandemic is a global outbreak of disease."

And yet words like "pandemic" and "epidemic" and "plague" carry a set of implications that cause many people to engage their mental yardsticks. I've heard many people express sentiments to the effect of, "If this is a real pandemic, why aren't the bodies piling up like in the Black Death?" The Black Death is a sort of core myth of Western culture at this point for epidemic, complete with the Monty Python image of people trundling along with carts calling "Bring out your dead!" It's a terrible, terrible disease (which is still out there and occurs in about 5,000 people a year globally, though it can now be treated with anti-biotics) but it is only one of a huge number of infectious diseases which used to account for the majority of human deaths.

If you look up the leading causes of death in the US at this time in history, you get the following list:

Heart disease: 647,457Influenza and pneumonia are the only infectious diseases on the list, and they're ranked 8th out of 10. It didn't used to be this way. A New England Journal of Medicine Piece provides this comparison of what people died of in 1900 vs 2010.

Cancer: 599,108

Accidents (unintentional injuries): 169,936

Chronic lower respiratory diseases: 160,201

Stroke (cerebrovascular diseases): 146,383

Alzheimer’s disease: 121,404

Diabetes: 83,564

Influenza and pneumonia: 55,672

Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, and nephrosis: 50,633

Intentional self-harm (suicide): 47,173

Influenza and Pneumonia topped the list, followed by Tuberculosis. All infectious diseases of different sorts. Why is influenza less of a killer now? For the same reason that tuberculosis and pneumonia are, to an extent. The influenza virus is not always the primary killer. Often it weakens the body and immune system which allows bacterial pneumonia to take over and finish the patient off. With modern antibiotics we can treat those bacterial pneumonias thus lessening the death rate of influenza. Additionally, we have the influenza vaccines which build the body's resistance to the virus strains themselves and we have antiviral medications which can help to some extent.

But influenza and other infectious diseases were fully capable of killing lots of people, and that was just in a normal time when there wasn't an epidemic on the loose.

What makes an epidemic different from run of the mill "endemic" disease? It's not necessarily that that disease is spectacularly deadly. A disease is epidemic when it is spreading through the population rapidly and infecting a large number of them. In theory this could happen with some fairly minor disease, so long as it was quite contagious and not many people have antibodies that protected them from it. The difference is just that if a minor sniffle spread rapidly through the whole population, we wouldn't notice it a great deal.

The point about people not having antibodies that protect them from the disease is key. Diseases are, after all, essentially parasites. A virus can't reproduce all on its own. It needs to take over the cell of another creature and commandeer that cell to manufacture copies of itself. Once the body recognizes a virus for what it is, a hostile invader, the body develops antibodies that destroy the virus. So imagine that I have a virus that's colonized my body and is using my cells to crank out copies of itself. I'm coughing out micro-droplets of water vapor which contain those viruses. But all the people I come in contact with are people who have already come in contact with that type of virus, and as soon as one of the viruses comes into one of these bodies, the antibodies destroy it. So even though the viruses that have taken over my body are cranking out copies of themselves, they can't successfully colonize any other bodies. After a couple weeks, my body too develops good enough defenses to start attacking the virus, and so my body wipes out the infestation of viruses in my body and it's the end of the line for that strain of viruses because they weren't able to colonize the bodies of any other people I came into contact with.

With an endemic virus, a common virus that's been around for a while in the population, a lot of the people the virus comes in contact with are already able to fight the virus off, and so spread is slow. We can see how that is important when we look at times when endemic diseases became epidemic diseases because they came in contact with a new population. After Europeans reached the new world, diseases that were common in Europe (measles, smallpox, influenza, etc.) but which had not before been present in the Americas suddenly turned into epidemics. Measles was not an epidemic disease in Europe. It has highly contagious, but lots of people had had it before and were immune. Even children who hadn't had it before received some antibodies from their mothers during pregnancy and nursing, giving their bodies a head start when they encountered the virus for the first time. But in the Americas, measles was totally unknown. The result was that what in Europe was a bad but survivable childhood disease became in the Americas a population decimating epidemic. Much the same happened with other diseases that had been common in Europe but not in the Americas.

That there were so many diseases that were common in Europe but not in the Americas is believed to be due to the fact that Europeans had domesticated many more animals and lived in close contact with them. Many viruses first jump to the human population via a mutation of some animal virus. For instance, the flu virus which caused the deadly 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic is believed to have jumped from swine to humans in Kansas in the spring of 1918. If you want to read lots of interesting discussion about virus mutation, immunities, and pandemics, I'd recommend John Barry's The Great Influenza which I've been reading and finding fascinating.

When a new strain of an existing family of viruses (such as the 1918 Spanish Flu strain of the influenza virus) appears via mutation and/or jumping from some animal species to humans, if it is different enough from other strains that the immune system does not recognize it, the virus can spread rapidly in much the way that these new diseases did in the new world. But even the case of a "novel" virus (such as the novel coronavirus that we're dealing with now) there can still be degrees of susceptibility. The 1918 influenza pandemic was a novel strain which was significantly more deadly than normal seasonal flu. Seasonal flu kills around 0.1% of those who get it. In 1918, the fatality rate was more like 2.5%, twenty-five times higher than "normal" flu strains. Moreover, while seasonal influenza mostly kills those we'd think of as medically fragile (infants and old/infirm people) the 1918 flu hit people in their 20s and 30s particularly hard. And while all lives are of equal worth, it's not unreasonable that people would consider particularly tragic a disease which suddenly cuts down healthy young people who appeared to have their whole lives before them. But that 2.5% fatality rate was not consistent everywhere. The fatality rate was much higher among isolated populations that had seldom been exposed to other strains of flu. For instance, Inuit villages in Alaska and Canada in many cases experienced much higher death rates, sometimes near 100%. The same was the case for Pacific Islander populations, Australian Aborigines, etc. It's believed that the reason for this is that populations which had experienced fewer outbreaks of other flu stains were even more defenseless against the virus that populations where people's immune systems had at least identified and fought off other flu strains. Even though this particular stain was novel enough that everyone was susceptible to it, the familiarity with other flu strains somehow gave the immune system enough of an edge that it was able to build its defenses more quickly.

Although SARS-CoV-2 is a "novel virus", it may be that exposure to other types of corona viruses is one of the things which causes some people to suffer little or not sickness from the virus, developing antibodies that can fight off the virus without the body suffering much of any damage first, while other people experience a long, difficult, or even fatal respiratory disease.

So is COVID-19 a pandemic? Well, it is a rapid outbreak of a disease which has spread across the world. It first appeared in China and has now infected significant numbers of people in Iran, throughout Europe, the US, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Ecuador, Turkey, Israel, India, the list goes on.

But as I said earlier, we could imagine a situation in which a disease was new enough that it swept across the world but in which the disease was not really that serious. What are we to say to the people who argue that COVID-19 isn't really killing many people, perhaps no more than an ordinary flu season?

I'd meant to get into the numbers question in this installment, but talking about the nature of pandemics took me longer than expected so I'll address numbers in the next installment, and at I'll also include a section of a the closely related topics: "lockdowns" and whether they have slowed the virus at all.

Click here for Part 4.

Friday, May 15, 2020

Charis in the World of Wonders, by Marly Youmans: A Review

I received a review copy of Charis in the World of Wonders, but my thoughts are all my own.

My Amazon review:

Gentle Charis, educated, red-haired, and the sole survivor of the massacre of her settlement, flees through the forests of the Massachusetts Bay Colony to rebuild her life in the more established towns near Boston. There she finds that the world holds other, subtler dangers than just the Mi'kmaq tribe and the French. Some Puritans are eager to see the judgment of God in the sufferings of others; some friendships end in grief. Sullen suspicions of witchcraft simmer around a girl who has escaped the dangers of the wild and who trusts that God seasons judgment with mercy.

Charis has heard old German fairytales, and echoes of those stories resonate in her own as she takes a position sewing for a dour widow with two headstrong daughters, who suspect the few precious possessions that remind her of her mother's care. But she also finds that the death of her family cannot kill love, and that grace and beauty are constantly breaking through the dull surface of the world, not least through a silversmith with silver eyes and golden hair.

Marly Youmans is a poet as well as a novelist, and her graceful prose sets Charis's terrors and joys in an authentic and sensitive historical voice. She weaves the strangely colorful language of the New England colonies into the story with a sure hand, and realizes the Puritans as a people of ecstatic vision of heaven as well as hell. (A glossary in the back of the book helps the reader over more obscure terms, though the reader may wish more for a map to trace Charis's wanderings.) The quiet lyricism and episodic pacing of the novel provides just enough distance from the sorrows of the story, as Charis wrestles with guilt and the trauma of her family's death, comforts an agonized new mother with no will to live, bears slander, and fears that once again she will have to flee from the world she knows into a wider world of wonders.

***

When I was asked if I would like a review copy of this novel, I was wary at first, because the promotional material I'd read was very vague and focused mostly on the poeticism (and other discerning readers have told me that they'd had the same hesitation). The novelist du jour of wonder is Marilynne Robinson, and terms of you can draw parallels between this novel and Robinson's Gilead in terms of realizing the wonder of the everyday world. However, I think I'd prefer a comparison with the novels of Ron Hansen, specifically Mariette in Ecstasy or Exiles. Ms. Youmans and Mr. Hansen share a deep commitment to moral questions not just pondered and wondered, but acted on even at the moment of mortal peril. Charis in the World of Wonders is a novel which demands real choices of the characters, in which wonder is not just a glistening opiate, but a sublime, dangerous glimpse of reality that demands a moral response.

Response, moral choice: these are key elements. I recently read The Diary of a Country Priest, by Georges Bernanos. This novel is classic Catholic literature, and it is very good, but large parts of it are characters laying out to one another their religious and political philosophies. There's nothing wrong with that, necessarily, but the language of the pressing discourse and class concerns of 1936 France can seem quaintly distant to readers of 2020. Bernanos was, of course, writing a contemporary novel, not trying to make historical debates relevant to a future audience. (The spiritual grapplings of the main character could also grow a bit wearing for the reader, who realizes that the priest's spiritual agonies are more than a little influenced by his deteriorating health, and that a good rest in a sanatorium might be more spiritually beneficial to a clearly dying man than one more disquisition about the state of the French worker.)

But as I skimmed one multi-page monologue after another, I found myself yearning for the moments of choice -- the moments when the grand philosophies and the agonized doubts played out, and people had to act on their convictions. And those moments were gripping. Indeed, the last page of the novel, describing how the priest faced a painful lonely death, is worth the whole rest of the book. It is what he truly believes, lived.

And so with Charis. There are necessary interludes where characters must grapple with pressing questions: did God ordain the deaths of my family? Are my sufferings a judgment on me? Is survival a mark of grace or a sign of diabolical alliance? And then Charis must accept grace and extend it to others, the small internal struggles no less dramatically significant than the external adventures. The comparison to Cinderella is apt, I think: grace is not less costly for being quiet and outwardly insignificant.

But when we speak of novels, we are also speaking of literary merits, and it is often the downfall of religious novels that the best of moral intentions become heavy-handed and didactic without literary ability. (And ability is often underserved without the attentions of an editor attuned as much to style as consistency and editorial guidelines.) So I am very pleased to see any Catholic publisher bringing out a novel by an established author with a sure literary style, and who sticks the ending. As anyone who has read any quantity of religion-adjacent fiction can testify, these qualities are by no means assured, and the difficulty of finding excellent new fiction is compounded by the tendency of reviewers to give a pass to literary merits to members of the tribe.

Ms. Youmans, as mentioned above, is a poet, and I'm aware that I myself am inclined to a plainer style. There were, to me, moments when poeticism threatened to undermine the narration. A small example: a pregnant character says of her child that "He clenches together and opens up like a thread of metal coiled up and pressed and released." That is a lot of words to describe a spring. If such a concept did not exist in the late 17th century, it would be exceedingly odd to invent it in this way. (Wikipedia informs me that coiled springs do indeed date back to the 15th century.) But more to the point, it was an overly complex image that drew too much attention to itself.

Why nitpick in this way? Because I think this is an excellent novel with few flaws, and I want to you trust that I read it and am giving you an honest review. I'd like to commend Ignatius Press for bringing out an important novel that deserves a place with any of the literary fiction coming from the major publisher, in a handsome edition with original artistic motifs at the head of each chapter. If anything is going to rebuild readers' trust in the inbred Catholic fiction industry, it will be a fierce attention to literary as well as moral integrity.