Tuesday, June 28, 2022

Crisis Pregnancy, a Personal History

Tuesday, June 21, 2022

Marriage Prep: Theory, Practice, and "How Far Can We Go?"

The Dicastery for Laity, the Family and Life released June 15 “Catechumenal Itineraries for Married Life,” a draft text published in Italian and Spanish,” with an introduction by Pope Francis.

In his introduction, the pope wrote that the document meets "the need for a ‘new catechumenate’ in preparation for marriage" — a need the pontiff said he has flagged before.

Describing difficulties the recommendations aim to address, Pope Francis wrote that:

“What emerged was the serious concern that, with too superficial a preparation, couples run the real risk of entering into a marriage that is null and void or has such a weak foundation that it ‘falls apart’ in a short time and cannot withstand even the first inevitable crises.”

The pope noted that the Church already devotes many years to the formation of candidates for the priesthood and religious life, and observes that in comparison the Church provides only a few days or weeks of active formation for couples approaching matrimony, which is a vocation of equal importance in the Church.

To fill this gap, the document prescribes a catechumenate of marriage, which Pope Francis described as follows:

“It is structured according to the three stages: the preparation for marriage (remote, proximate and immediate); the celebration of the wedding; the accompaniment of the first years of married life.”

The situation

The family is, according to the Church, the foundation of human society.

But while the number of Catholics in the world has increased 17% over the last 12 years, the number of marriages celebrated by the Church has decreased 26% over that same period of time, according to statistics released in the Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae.

Indeed, in every region of the world, the number of marriages celebrated within the Church has dropped in relation to the Catholic population between 2007 and 2019 — in some cases drastically.

The article includes plenty of charts and graphs tracing these trends.

We had a year-and-a-half engagement, which was quite correct for our situation as college students, and yet I still believe it would be an abuse to mandate a longer "catechumenate of marriage" engagement period, because every couple is different. Had we met after college, we might have married within six months. As we approach our 21st anniversary next week, it's an amusing exercise to reflect on the fundamental uselessness of our own marriage prep. We took (separately) a FOCCUS questionnaire, which is a tool to assess whether a couple has (or thinks they have) discussed certain necessary topics, and whether there are are areas of disagreement that should be addressed before marriage. Here's a sample of the questions. Some friends did find it helpful -- "Oh, maybe we should be talking about finances before we get married!". As for us, the priest whose job it was to go over the assessment with us looked at our scores, then looked at us and said, "I'm not saying you cheated, but I've never seen a couple have almost 100% overlap on their answers."

This was before we took our marriage prep classes, and nothing in those classes would have changed our answers, or indeed have contributed in any way to improving our fitness for marriage. What would have been vastly more informative (and interesting) would have been to talk through an annulment assessment, both together and with a priest and/or mentor. Here's an example of such a document, from the tribunal of the Archdiocese of New Orleans. This is not a bulletproof cure-all, but it might improve the psychological health of many relationships to address, before taking vows, the kinds of issues that will surface later and cause a lot of pain and turmoil. You deal with your issues, or (sooner or later) they will deal will you.

But there is also never any relationship that will be free from pain and turmoil. We are human, and to be human is to be constantly growing into deeper spiritual realities that are beyond our human capability to handle. "Die to self," says Jesus, and this isn't prescriptive, but descriptive. We will die to self. We are constantly dying to self, confronted with pain and glory -- or painful glory -- that breaks and remakes us. Marriage provides an excellent school of death to self, because you are intimately entwined with a person who is not you, who, despite the deepest human love, you cannot save and who cannot save you. It is a source of pain because growth is painful -- not because it's bad, but because it's stretchy. And pain is diagnostic. It warns you that something is changing. And change is not always bad!

This is something, incidentally, that would have been almost incomprehensible to me when I took marriage prep, because I had the utter confidence (justified, I might add) of marrying my best friend whom I would never do anything hurt, and who would never do anything to hurt me (which, 21 years later, is still true). And I did not understand, and might not have believed it if I had been told so, that pain is caused not only by sin, which we have striven hard to avoid, but also by growth, which is unavoidable. If you are not growing you are dying -- and that's painful too.

Perhaps the only way to explain it is by using the story of the coal with which the angel touched Isaiah's mouth (Is. 6:6-7), which gave him the grace to speak clearly and openly, and probably hurt like hell. Never, in our 21-year marriage or our 25-year friendship, have we spoken an unkind or abusive word to one another, and I call our friends and children (who naturally have a love of dishing on their parents) as witness. But we have had to speak words that hurt -- or, rather, words that we held in for fear that they might hurt the other, which, when finally spoken, led to loving, fertile conversations. I believe this is the true submission spoken of in Ephesians 5, and it calls for much more vulnerability and Christ-like humility than the garden-variety weirdness promoted by the "husband as head of the household, dammit!" interpretation.

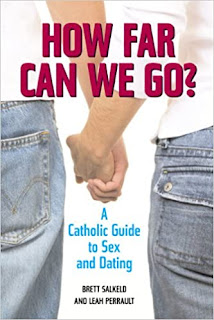

In our household, we are trying to provide our children with a years-long catechumenate of marriage, so that they are not playing catch-up when it comes to the more immediate period of preparation. The first and most vital way we do this is through our own example, and I think we do okay. But even the finest example needs to be supplemented through active teaching. One of the best Catholic books about sex and relationships for teens and young adults is How Far Can We Go?, A Catholic Guide to Sex and Dating, by Leah Perrault and Brett Salkeld.

Of all the vast collection of guides to chastity for Catholics, this has been truest to our lived experience as young adults who navigated a deepening, increasing intimate relationship while saving sex for marriage. Ten years ago, I wrote a review of this book which is still our most viewed post, and ten years later, I've given my three oldest daughters their own copies -- autographed, as it happens, because Brett Salkeld recently sent me five copies for us to keep or donate.

Two of those copies are for you, dear readers. If you would like to be entered in our drawing, please comment below. (If you want to comment without being entered, you can of course do so, but let me know.) On Friday we'll pull a name out of Eleanor's battered hat, and post the winners both as an update to this post and in the comments.

AND THE WINNERS ARE: LadyHobbit and Mandamum!

Saturday, June 11, 2022

A New Commandment

"I give you a new commandment: love one another." -- John 13:34

It seems strange for Jesus to label this a new commandment, since elsewhere he points out that many people already love each other: parents giving their children good things; the pagans who love those who love them. In fact, Jesus's greatest parable, The Prodigal Son, involves not enemies learning to love each other, but a natural love, the extravagant love of father for son.

What is new is not the love but the commandment, the permission. What Jesus is describing in The Prodigal Son is striking not because is something unprecedented, but because it is familiar to all his listeners: the parent who loves to the point of looking weak and foolish; the father who forgives when the world allows that he has a right to hold back. Jesus tells a story about human behavior since the beginning. The Old Testament provides plenty of examples. David and Absalom. Hosea and his unfaithful wife. Isaac, who protects Jacob from Esau's wrath even after Jacob has stolen the birthright. The slave girl who tells her master Naaman how to find healing from his leprosy. It's not that no one ever loved and forgave before Jesus came. It's that such love was seen as weak and shameful and unworthy. And so people continued to show mercy, and to feel conflicted about that mercy.

Jesus comes with a new commandment: the love that seems weak and pathetic is the love he commands. The father who seems like a chump actually loves as God loves. He is not breaking the old commandment, but following the new. And that love marks him, no matter his place in human history, as an exemplar who points the way to Jesus.