A few weeks ago, I posted a first chapter to a book that I'm writing "for work", writing about pricing in the context of my experience a decade back managing pricing for the fast food chain Wendy's.

When I say "for work" it's not at the request of my current employer. But as the company I work for moves towards being sold by the private equity company that owns us, I am thinking about starting a price consulting company as my next step. And if you want to be a pricing consultant, it doesn't hurt to have a "business card" kind of book which shows off your expertise on pricing.

Often these books are written to impress other pricers, and so they are focused on mechanics of pricing theory or how to run a pricing department. My thought is to try to write a somewhat more accessible book aimed as business owners and the general public, and explaining through the medium of something we all know (fast food) how pricing works in a business.

My hope is this would be moderately successful as a book, as an advertisement to potential clients, and as a "here, let me give you a copy of my book" tool when seeking business.

Anyway, I probably will not post the whole thing here in installments, but I did think I would post at least one or two more chapters in order to get feedback and to write the way I'm used to: with a live audience.

So, here is. As before, feedback very much welcome. Is it readable? Would you enjoy this book?

Chapter 2: The Power of Pricing

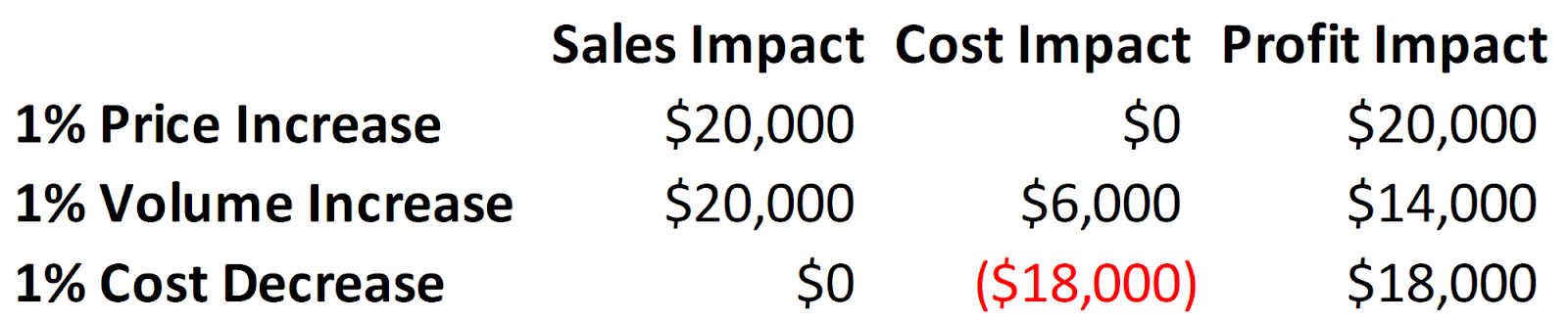

Picture, if you will, that you manage a successful fast food franchise restaurant. Over the last year, your total sales were $2 million, with expenses of $1.8 million, meaning that you made a 10% profit.

One day, you are cleaning up and – after rubbing an old bronze lamp which mysteriously surfaced in the maintenance closet – you are visited by the Business Genie, who offers you just one wish.

By magic you can choose to:

- Increase your prices by 1% while selling just as many items every day

- Increase your volume by 1% (selling 1% more items every day at the same prices and costs you have now)

- Decrease all of your costs by 1%

Which should you choose?

Would the effect of each be the same? All the changes are 1%, after all.

Not at all.

Given this set of assumptions, the price increase is the best choice. It would increase your annual profits by $20k. Next best is the cost reduction, which would be an $18k increase in profits. Going with the volume increase will net you only $14k in increased annual profit.

It’s pretty clear why increasing your price 1% on $2M will result in a $20k impact, and why decreasing $1.8M in costs by 1% results in a $18k decrease in costs, but the reason why I’m estimating the cost increase which comes with selling 1% more volume at $6k could use additional explanation. For the moment, I’ll just say that if you sell 1% more burgers, you have to buy 1% more burgers, but you don’t necessarily have to pay 1% more in rent and 1% more in wages.

Since in this example your annual profits were $200k to start with, that 1% increase in price has boosted your total profit dollars by 10%.

Professional pricers love to share this kind of example. Indeed, if you’ve read a number of books on pricing or attended multiple pricing conferences, I owe you an apology, because you’ve probably heard this kind of thing many times before.

But although to some extent we pricers share this kind of example because it makes us and our services important, there’s a vital lesson to be learned here. Too often, decision makers trying to grow their business put most of their effort into pulling on the less powerful levers in their business (cutting costs or increasing volume) and miss the power of the pricing lever.

So indulge me here (or skim ahead if you must) while I discuss these three levers and why the pricing one is so powerful.

Increasing Volume

If you want your business to make more money, perhaps the most natural thing to think of is, “How can I sell more?”

As a professional pricer, I’d love it if more people hired me to analyze their pricing. As an author, I hope lots more people buy this book. When you run a QSR location, you want more people pulling into the drive thru.

At first blush, it might seem like more volume is simply more volume, but when it comes to analyzing the advantages and pitfalls of volume and how you get it, it’s worth looking at the type of incremental volume you’re getting.

There are two basic ways we talk about more sales in the QSR industry: more tickets, and larger tickets.

More tickets means more individual people buying food from the restaurant. Whether someone walks into the store and approaches the register, or, like about 80% of customers they pull into the drive thru, each customer order is a ticket.

All other things being equal, more tickets means more revenue. But how do you get more tickets?

There are so many ways: Have a welcoming dining room experience so seniors and young families pick your location as a place to come get something to eat and socialize. Offer exciting new limited time menu items which people want try before they are gone. Open earlier or stay open later, so that people wanting to eat at odd times come to your store. Advertise so that people who see or hear your ads crave the food you serve.

Some of these tactics come with their own extra cost. Being open longer hours means you have more wage expenses to cover. Advertising always has some cost, whether it’s a radio jingle or just a vinyl sign on stakes out by the road. New food offerings have an R&D cost and perhaps the cost of bringing in new ingredients which are only used in that specialty product. And, of course, no one will be craving your seasonal product if you aren’t advertising it somehow, even if it’s just a delicious picture on the drive thru sign.

But even setting aside the extra cost of trying to get more volume, when those extra people come to your store they all buy food, and that food has a cost. This means that if you get ten extra people into your store each day, and each of those people spends ten dollars (10 tickets X $10 = $100/day), your profits don’t go up by one hundred dollars. Your profits increase by $100 minus the cost of the food on those tickets and minus any money you spent to bring those extra people in.

How much cost is involved in selling that extra $100 worth of food can be a tricky question.

In my simple example which opened this chapter, the overall store has 10% margins.

Say that in this example where ten more customers come in each day, you didn’t spend any more on advertising and you didn’t increase the hours you are open. You also don’t have to bring in extra staff in order to serve the additional customers who come in ordering food. Let’s also assume that any additional work you need to do in order to serve those extra customers does not end up increasing the cost of your maintenance or utilities.

In that case – if we use our simple assumption that your cost structure is 30% food cost, 30% labor cost, 30% site costs – your labor costs and site costs remain the same. On the extra revenue you make from serving those ten extra customers each day, you’ll make a 70% margin instead of a 10% margin.

Or in the case of our Business Genie offering to increase volume by 1%, if that increase in volume incurred no extra labor costs or site costs, the increase in annual costs would be $6k ($20k in revenue minus 30% food costs on that $20k) and the increase in profits would thus be $14k.

What this breakdown is getting at is the difference between what are called variable costs and fixed costs. In this very simple model, we’re treating food costs as variable costs (you can’t sell more burgers and fries without buying more patties, buns, and fries) while treating labor and site costs like rent as fixed.

The distinction is clearly important. It matters a lot to the profitability of selling one more hamburger that that hamburger itself only increases your costs by the expense of its ingredients.

However, the distinction isn’t truly fixed. With sufficient volume, all costs become variable. Imagine that instead of one or ten more hamburgers a day, you sold 1,000 more each day. Now you definitely need more people. And a bigger fridge to store your patties. Maybe you even need a bigger location or to open a second location to serve all that customer demand.

And of course, short of our magic Business Genie, getting more people to visit your store each day seldom comes free. Usually you’ll be doing something to get those people to come: putting up signs or running ads or announcing a discount. All of those ways of increasing your volume have their own costs. And if you are going to spend money in order to increase your sales volume, you need to ask yourself what the actual profit on the additional sales volume will be, versus the cost of your volume driving activities.

As you make that calculation, you’ll need to think about what costs are going to increase as your volume increases, and that answer will vary depending on how many additional people come, when they come, and what they order.

***

Getting more people to visit your store each day can be hard. Wouldn’t it be great if you could simply get all the people who already visit your store to each buy a little bit more?

As I said, there are two ways to increase your volume at a QSR: more tickets or larger tickets. Since it’s hard to get more people to visit your store, it’s often tempting to instead focus on getting your existing customers to buy more items or more expensive items on each ticket.

The classic example of expanding the ticket in fast food is the phrase everyone has heard, “Would you like fries with that?”

Or to take things one step further, “Would you like to make that a combo?”

The fast food combo is a great example of expanding the ticket. It takes a customer who is already buying an item, and encourages him to add two more items: fries and a drink.

Of course, the combo price also represents another pricing trade off: a discount. When you buy a combo meal, the price is lower than if you had bought the entrée, fries, and drink each à la carte. Discounts present a whole other set of pricing trade-offs which we’ll address in a later chapter.

The other way of expanding the ticket may not seem as immediately obvious: offer the customer an option which is more expensive, but also more enticing, than what they would otherwise have bought.

If I head to a local Wendy’s planning to pick up a standard cheeseburger, but end up buying a Big Bacon Classic or a Pretzel Baconator, I’ve just increased my ticket size even if I’m still just buying the one sandwich.

These two approaches to increasing the ticket – selling more items to each customer or getting the customer to trade up to more expensive items – represent two important ways of maximizing the profitability of your existing customers in any business.

Both these approaches to expanding the ticket – adding fries and a drink or upselling the customer to a more expensive product – allow us to think for a moment about another important QSR dynamic: Not all products have the same profit margin.

Up till this point we’ve talked about an average food cost of 30% of revenue. That’s a typical overall food cost ratio for a QSR location. But not every item is 30% food cost. Some are less, and some are more.

A hamburger on the value menu (back when the popularity of the $0.99 or $1 price point for value items made it essential to have several value sandwiches at that dollar price point) often had the highest food cost percentage on the menu. When I ruined my future coworker’s college experience by taking the Junior Bacon Cheeseburger off the value menu, a rapid increase in bacon costs had driven the food cost of that item up above 60%.

Fountain soft drinks and ice tea had some of the lowest food cost on the menu. A fountain soft drink consists of water which has been put through the ice maker, more water which has been carbonated with a tank of CO2, and a bit of sugary flavor syrup. Water which flows into the store in the pipes from the city water supply is very cheap, and only very small amounts of the CO2 and syrup are needed for each cup. Often, the cup is the most expensive part of the drink.

While a full size hamburger or chicken sandwich is around 30% food cost, a soft drink might be only 10% food cost with much of that coming from the cup (not literally food, but considered part of the food cost since “food cost” in QSR is essentially what “material cost of goods sold” would be in a manufacturing business.)

This means that adding a soft drink to a fast food meal not only increases the size of the ticket, but also significantly increases the profitability. French fries are not quite as high margin as soft drinks, but they are significantly more profitable than sandwiches, so the drink-and-fries combo is a real profit maker.

It’s worth a brief digression on why fountain drinks are so profitable. You would not do nearly as well adding a bottled or canned drink to a meal. Why?

Napoleon said: “Amateurs discuss tactics, professionals discuss logistics.”

The general would thus have appreciated the wonderful thing about fountain drinks: when a customer pulls out of the drive through with a 30oz Coke nestled in his cup holder, most of the weight he’s driving off with is in a vehicle for the first time.

The cup, lid, and straw were brought to the location in a truck, as were the canisters of compressed CO2 and the flavor syrup. But cups and lids are stackable and very light. A case of 500 cups might weigh around 25 pounds.

By weight, the largest contribution to the final drink which had to be carried to the restaurant by truck is the flavor syrup. A soda fountain mixes carbonated water and flavor syrup in a 5:1 ratio. So if a 30oz cup (which with lid and straw weighs less than two ounces) has 10oz of ice and 20oz of soda, it contains just over 3.3oz of flavor syrup.

Only about 5oz of the 30oz drink had to be trucked to the store. The rest of the weight arrived via the city water pipes, and is thus incredibly cheap. Pipeline systems are expensive to install, but once in place very cheap to operate.

A 30oz fountain drink thus only has a freight-weight which is 75% less than a 20oz bottled soda. That makes it cheap (as well as somewhat more environmentally friendly) because liquids are heavy and thus shipping liquids on trucks is expensive.

If you watch for trends in the prices when you go grocery shopping (and as a professional pricer, I can’t help doing so) you’ll notice that in periods when trucking costs increase significantly, heavy products (which often means liquid products) increase in price: soft drinks, bottled water, milk, etc.

That’s because when a comparatively cheap product weighs a lot (like a 8.33lb gallon of milk which retails for $3.49) the cost of transporting the product from its source to the store becomes a significant part of the overall cost. And thus, changes in the cost of transportation (due to diesel prices or availability of trucks and truckers) have a larger effect on the cost of those products than on ones which are lighter or more expensive.

So to bring this digression back to its beginning: fountain drinks are among the cheapest things on the fast food menu. When a customer rounds off the ticket by adding fries and a drink to his meal, it not only expands the ticket, but does so with items which are higher margin than the entree they are added to.

Decreasing Cost

Tell a manager that he needs to increase margins, and the first thing he will typically think of is to reduce costs.

Psychologists point out that we humans are loss averse. We are particularly aware of having things taken away from us, sometimes so much so that we focus on avoiding loss even when making a different choice would provide a good chance to gain even more. Costs take our money away, and so we tend to be very aware of them.

However, as the hypothetical which begins this chapter points out, reducing cost is a pretty good way to increase profits. Moreover, it can seem like the way which is most under the control of the manager.

Increasing your sales means relying on more customers to show up, or each customer to buy more.

Increasing your price relies on the customer’s willingness to pay higher prices, rather than going to a competitor or buying less.

Find a way to reduce your costs, and you can rely on having those savings in hand.

In our example, the cost reduction was magical, which of course makes it very simple. But let’s take a few moments to think about the different ways that a business can reduce cost.

As mentioned in the previous section, costs can be broken down into fixed costs and variable costs. Perhaps the simplest cost reduction is to reduce the cost of the materials used to make the product you sell. If you sell hamburgers, and you can get your ground beef, buns, lettuce, and tomatoes for less money (while keeping your prices the same) you will make higher profits.

There are three ways you might achieve this: A commodity cost reduction, negotiating with your suppliers, or reducing the quantity or quality of the materials you use to make your product.

The cost of raw materials varies over time. General inflation is when all prices in the economy go up by roughly similar amounts because the money supply gradually increases. It’s normal for there to be low but steady inflation over long periods. Modern central banks try to fine tune the economy to make sure that there is low single digit inflation: not too much, but always some.

However, various goods your business might buy – whether foods like beef, wheat, and bacon or industrial materials such as steel, aluminum, and coal – also vary in price over time independently from general inflation, based on changes in their availability.

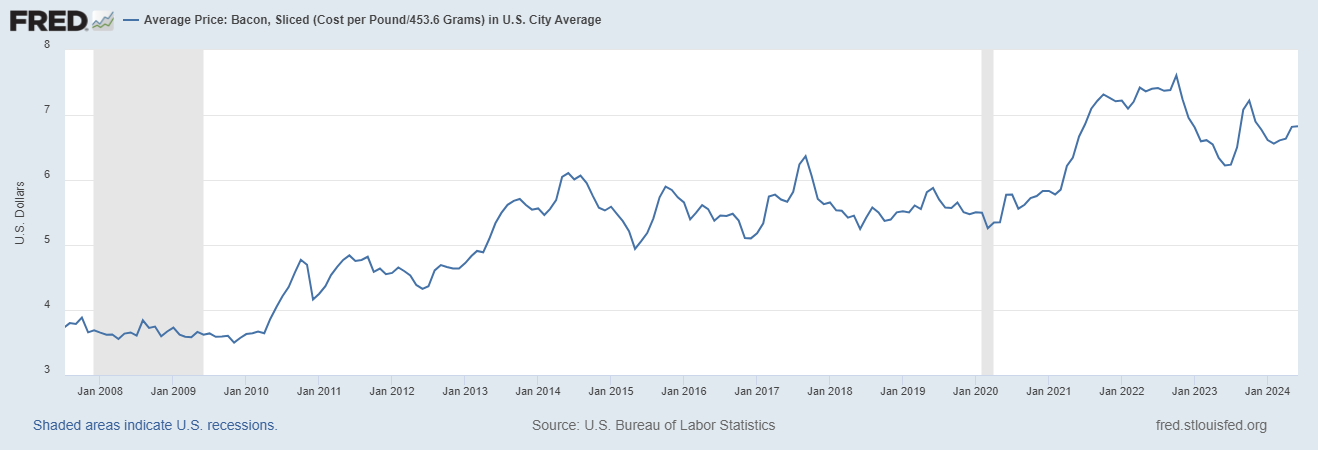

For instance, here is the data from the Federal Reserve showing the price of a pound of bacon in the US since 2008. After remaining relatively flat for more than two years, in mid 2010 the price of bacon increased by about 30%. It was this increase in the price of bacon, during my time as pricing manager at Wendy’s which caused us to remove the Jr. Bacon Cheeseburger from the $0.99 menu.

Over long periods of time, due to inflation, the general trend is upwards. However, there are periods when the price decreases. For instance, according to this data, in October of 2022 the average price of a pound of bacon reached $7.60. Since then the price has varied – currently it sits around $6.80, about 10% below the high – and has not again reached the high from the fall of 2022.

If you had set the price of your restaurant’s bacon cheeseburger based on that 2022 price, and your cost of bacon has since fallen 10%, you could increase your profits by just keeping your prices the same.

It’s nice work if you can get it, and if your competitive environment allows you to keep your own prices stable when your costs fall like this, you should do so. It will allow you to increase your profit margins and build a cushion against the next time costs rise.

But commodity market deflation cannot be summoned up at the business owner’s wish. So while it’s true that you can use a conveniently-timed decrease in commodity costs to increase your margins, you are dependent on events for the opportunity.

If cost increases aren’t coming to you via the commodity markets, another approach to reducing your costs is to simply demand that your suppliers decrease their prices if they want to continue doing business with you.

Will that work?

Outside of a wish-granting genie, the difficulty with reducing your material costs in this way is that if you are simply paying your supplier less for the exact same quality and quantity of materials, you may be increasing your profits, but unless the broader market cost is going down, he is seeing his profits shrink.

One thing that surprised me working in the quick service restaurant industry was that major restaurant chains do not actually get their ground beef significantly cheaper than consumers do at the grocery store.

The market for beef is controlled by the fact that the total demand is moderately stable and the supply cannot change too quickly since it takes about two and a half years to produce beef, from breeding to slaughter.

Cattle growers and processors work at narrow profit margins, but they won’t choose to sell below their costs. Thus there is a clear bottom limit to what price they will sell at, no matter how big the McDonald’s or Wendy’s supplier contract might be. Nor can a potential competitor produce the millions of pounds of beef needed upon demand.

As a result, once the supply chain for fast food beef has been optimized for efficiency, there are only very small, incremental savings which can be wrung out of it.

For the consumer, on the other hand, there is another source of savings available, since grocery stores are sometimes in a position to sell short term excess amounts of beef at a discount. Or, failing that, grocers may choose to bring customers in their doors by making ground beef a loss leader.

Large companies like fast food chains are committed to wringing every last ounce of metaphorical fat out of their supply chains, and those efficiency savings definitely go to increasing their margins by driving their costs down, but even so there is extremely limited benefit to be found in simply demanding that vendors cut prices.

That’s why chains are often tempted to take the third route and reduce costs by reducing quality or size.

The power of reduced size can be seen in the patty sizes of value menu hamburgers. When I was managing prices at Wendy’s, it was the era of the $0.99 or $1 menu, with each major chain offering several items at the dollar price point. Today, due to overall food price inflation, value menu prices are higher.

However, either way, the hamburgers you see on these menus, such as the McDonald’s Classic Burger, the Wendy’s Jr. Hamburger and the Burger King Jr. Whopper use beef patties half or less the size of the standard quarter pound full size hamburger patty.

McDonald’s has the smallest value patty, at 1.6oz. Wendy’s value patty is 1.8oz, and Burger King’s is a full 2.0oz

This means as the three major chains competed to provide value menu offerings, the chains with the smaller patties always had a cost advantage against those with larger ones. The difference between a 1.6oz beef patty and a 2.0oz one is small enough to be non-obvious to customers. And yet, spread across millions of burgers, a 20% smaller amount of beef is a very significant savings.

These kinds of money-saving product size changes are so common among consumer packaged goods that the tactic has earned its own name: shrinkflation, so named because in terms of value per dollar it is a price increase on the customer achieved through subtle reduction in product size.

Packaged products ranging from potato chips to potting soil have seen package sizes reduced over the years (while prices remain the same or higher) as a way to increase margins by cutting costs.

Because fast food menus feature single serving items, such changes in size are less frequent. Customers may not notice if your patty is 1.6oz instead of 2.0oz, but they’ll certainly notice if you take away another 0.2oz ever year or two.

However, other forms of cost reduction are more easily achieved. Sometimes this involves taking out preparation steps or moving to cheaper ingredients: no longer toasting the hamburger bun on the grill, or going from full leaves of lettuce to chopped lettuce.

But there is, of course, a risk. Take too many of those moves, and your customers will start saying that your product just isn’t as good as it used to be.

If a product becomes perceived as too cheap as a result of repeated cost cuts which are also quality cuts, it becomes necessary to either introduce new, higher quality products while relegating the old ones to a down menu value position, or to conduct a product refresh in which quality is put back into the product. Sometimes this kind of product refresh, if marketed correctly, can even create an opportunity to increase the price.

We’ve looked at three ways to reduce the cost of producing the product. But could you reduce your fixed costs instead?

These might be some of the most difficult. Rent seldom decreases. No worker wants to accept a pay cut. But one key way to reduce fixed costs is through efficiency. If you could run your restaurant with fewer people, even if those people made more money per hour than before, your costs would be lower.

Sometimes this might involve time saving technology which allow one worker to get more done. But other times it might be as simple as thinking about the best times to be open.

Why is it hard to find a restaurant open in the middle of the night?

It takes a certain minimum number of people to run a quick service restaurant. At a slow time, you might be able to get away with one person who ran the register, poured the drinks, and wore the drive-thru headset, while a second ran the grill and a third ran the friers. But if business is slow, those three people would be serving fewer customers.

If the number of customers coming in the hours after 10pm is low enough that your crew is sitting around half the time, you would save money by not being open until midnight.

Of course, everywhere there are trade-offs. If your location becomes known for not being open late, it may be that fewer people will stop at other times. If someone remembers that she came at 11:30 and found it closed, she may not bother to stop by when it’s 9:45, even if you are in fact still open.

But while the existence of trade-offs means that it’s important to test, and there may be some other loss when you make a cost-saving change, it is certainly possible to optimize costs. It’s just not quite as easy as the magical 1% with which we started the chapter.

As we saw, decreasing costs has a significant impact on profits. However, as this discussion of costs has shown, decreasing costs is complex. The ways you might try to decrease different kinds of costs vary significantly. Paying less for your ingredients is different from using less ingredients which is different from using less labor which is different from trying to pay less rent or utilities.

Every successful business owner is focused on keeping costs down, but achieving significant cost reductions in order to boost your margins can be a tall order unless you’ve been lax with costs in the recent past.

And so, at last, we come back to pricing.

Increasing Prices

Why is it that increasing prices has the largest effect on your profits in the example with which we started this chapter?

Increasing prices is the only way to increase your revenue without any increase in expense. If you charge $6.99 for a hamburger instead of $6.39, your revenue increases by $0.60 while your expenses remain exactly the same.

The risk, of course, is that at the new higher price, fewer people will buy.

People will pay your prices if they consider the product to provide as much or more value than the next best option, taking into account their relative prices.

That “value” of course is a thing which is different for different customers and at different times. And the customer always has the option of buying nothing at all, if none of the options provide sufficient value for him to part with his money (or if he simply doesn’t have the funds available.)

We’ll spend much of the next chapter looking at how an increase in your price may cause some people to decide your product does not provide enough value for the money, and thus not to buy. The relationship between the increase in price and the loss of unit sales is called Price Elasticity, and it is something you can measure for your business in order to make intelligent (and profitable pricing) decisions.

But for now, the important thing is what increasing your price does: It allows you to make more money on each interaction with the customer. Each item you sell, to each customer who comes in the door or up the drive-thru, makes you more money without costing you any more than before the price increase.

That makes it the most powerful way of increasing the profitability of your business. It’s just math. Your revenue is the largest pool of money in your business, and if you can increase it without increasing your costs, your profits will go up.

The reason why people do not simply raise prices every day is that if you are not careful, and you increase your prices beyond the value your customers think you offer, you will lose sales and may end up worse off.

Our job, as pricers, is to figure out how to optimize your prices: how to make sure that your prices match the value of your products in the best way to meet your profit and sales goals.

To do that, we need to understand how changes in price cause changes in sales volume. That is the subject of the next chapter.