In

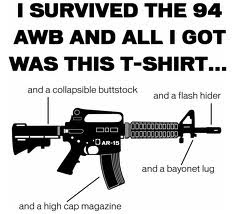

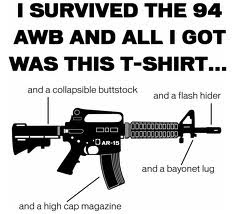

Part 2 I described the essentially cosmetic characteristics which were used to define some civilian rifles based on military assault rifle designs as "assault weapons" in the 1994 Federal Assault Weapons Ban (AWB). During the ban period (1994 to 2004) and even more so since, military style rifles have become dramatically more popular in the civilian market. The AR-15 (the family of civilian rifles based on the military M16) is now the most popular type of civilian rifle in the US with

dozens of models on the market. However, these rifles continue to have a very bad reputation with gun control advocates and they have been used in several recent highly publicized crimes such as the Aurora, CO movie theater shooting and the Newton, CT school shooting. This has led to renewed calls for increased regulation or outright bans of "assault weapons". In this third and final post on the "assault weapon" issue, I'd like to address the following issues: How often are military style rifles used in crimes? Are they particularly suited to crime? Did the 1994 AWB have any discernible effect on crime? Do military style rifles have legitimate civilian purposes?

How Much Are "Assault Weapons" Used In Crime?

The Coalition to Stop Gun Violence takes a fairly standard line on "assault weapons" in its page on the topic:

Assault weapons possess features specifically designed by the world's militaries to make it easier for the shooter to fire a sustained, high volume of rounds into a wide area. As a result of America's weak gun laws, these weapons entered our civilian marketplace decades ago, and criminals quickly learned how to exploit their military features.

However, these claims about the widespread adoption of military style rifles by criminals do not seem to align well with the facts.

According to a report this year by the Congressional Research Office "By 2007, the number of firearms [owned by US civilians] had increased to approximately 294 million: 106 million handguns, 105 million rifles, and 83 million shotguns." (page 8)

However, according to the FBI's uniform crime report, only 3.6% of murders are committed using rifles, a number that would include both "assault weapons" and more traditional rifles. Rifles were outranked in numbers of murders committed in 2010 by handguns (60.2% of murders), knives (13.1%), fists, kicking and other uses of the human body (5.7%), blunt objects (4.2%) and shotguns (3.7%). Another way to think of this is: Although there are roughly the same number of rifles and handguns available in the US, handguns are used in homicides at a rate nearly 17 times that of rifles.

A 2004 report prepared for the National Institute of Justice to assess the effectiveness of the (then expiring) Federal Assault Weapon Ban wrote:

Numerous studies have examined the use of AWs in crime prior to the federal ban. The definition of AWs varied across the studies and did not always correspond exactly to that of the 1994 law (in part because a number of the studies were done prior to 1994). In general, however, the studies appeared to focus on various semiautomatics with detachable magazines and military-style features. According to these accounts, AWs typically accounted for up to 8% of guns used in crime, depending on the specific AW definition and data source used (e.g., see Beck et al., 1993; Hargarten et al., 1996; Hutson et al., 1994; 1995; McGonigal et al., 1993; New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services, 1994; Roth and Koper, 1997, Chapters 2, 5, 6; Zawitz, 1995). A compilation of 38 sources indicated that AWs accounted for 2% of crime guns on average (Kleck, 1997, pp.112, 141-143).

Similarly, the most common AWs prohibited by the 1994 federal ban accounted for between 1% and 6% of guns used in crime according to most of several national and local data sources examined for this and our prior study (see Chapter 6 and Roth and

Koper, 1997, Chapters 5, 6)

...

Although each of the sources cited above has limitations, the estimates consistently show that AWs are used in a small fraction of gun crimes. Even the highest estimates, which correspond to particularly rare events such mass murders and police murders, are no higher than 13%. Note also that the majority of AWs used in crime are assault pistols (APs) rather than assault rifles (ARs). Among AWs reported by police to ATF during 1992 and 1993, for example, APs outnumbered ARs by a ratio of 3 to 1 (see Chapter 6).

From all of these, it would seem that military style rifles simply are not used that much in crime. This should not actually be all that surprising. The reason why the modern assault rifle is such an effective military weapon is that it is able to deliver accurate fire (and do so rapidly enough to allow a single soldier to tie down multiple enemy soldiers) at a distance of up to several hundred yards. This function (delivering accurate fire out to several hundred yards) is useful to civilian sport shooters as well, but it is of no use to criminals, who generally are using guns at a distance of just a few feet. That is why handguns are favored by criminals. Long distance accuracy and even rate of fire are not nearly as important in crime. Indeed, in most crimes employing a gun, the gun is not even fired; it is used as a threat. Far more important to criminals is the ability to carry a gun without it being seen until it is produced. Rifles, however military in appearance, do not fit well in a pocket.

Compactness is also the reason why handguns are primarily used by civilians in self defense. According to the same Congressional Research Office report cited above (page 13):

Another source of information on the use of firearms for self-defense is the National Self-Defense Survey conducted by criminology professor Gary Kleck of Florida State University in the spring of 1993. Citing responses from 4,978 households, Dr. Kleck estimated that handguns had been used 2.1 million times per year for self-defense, and that all types of guns had been used approximately 2.5 million times a year for that purpose during the 1988-1993 period.

This would suggest that while handguns are used in 89% of murders that are committed with guns, they are also used in 84% of cases of self defense. (As with the use of guns in crime, in the majority of cases of self defense, the gun is never fired, it is only drawn as a threat.)

Military rifles do seem to hold an attraction to some people bent on mass kills, as shown by the use of AR-15 rifles by the killers at Aurora, CO and Newton, CT. However, these cases are incredibly rare, only a handful over the last decade, as compared to the millions of military style rifles owned and used by completely law abiding citizens. Nor are military style rifles in any way required to perpetrate horrific mass killings as examples such as the Virginia Tech shooting demonstrate. Although gun control advocates tend to emphasize that "assault weapons" are designed to be fired "as fast as possible", the fact of the matter is that the civilian rifles which are termed "assault rifles" do not fire any faster than more traditional designs of semi-automatic rifles, or than pistols and revolvers. Virtually all handguns manufactured in the last 100 years, and a significant percentage of the rifles manufactured in the last 50, can be fired as fast as the trigger can be pulled. The attraction of military style rifles for mass killers is not that they offer some technological edge in killing that other guns do not possess, it is that their appearance ties in with their deluded images of themselves, allowing them to think of themselves as looking more deadly. In this sense, the selection of a gun with a military appearance is much the same as the selection of "tactical gear" which often serves little practical function for the crime planned, but which allows the killer to imagine himself to be military and dangerous in appearance.

Did the 1994 AWB Reduce Crime?

Murder rates and violent crimes rate did fall significantly from roughly 1994 (the year when the AWB was enacted) through 2000 and have remained flat to slightly down since that time. However, rifles (and thus necessarily the subset of military-style rifles) remained a roughly stable (and very small) percentage of guns used in crimes throughout the period.

The National Institute of Justice Report showed some evidence that military style rifles were used less in crimes after the 1994 ban (pages 42-45) however it also noted that since rifle manufacturers came out with legal ban-compliant versions of their military style rifles, the actual number of military style rifles sold went up during the ban rather than down (page 35-36). Given this increase in sales of military-style rifle and the fact that the "ban" did not actually remove any of the existing "assault weapons" from circulation, it seems likely that any small change in the rate of their use in crimes would have been coincidental.

Altogether,

the NIJ conclusion that the ban had little clear effect on crimes seems pretty likely:

Should it be renewed, the ban’s effects on gun violence are likely to be small at best and perhaps too small for reliable measurement. AWs were rarely used in gun crimes even before the ban. LCMs [large capacity magazines, defined by the AWB as magazines holding more than ten rounds] are involved in a more substantial share of gun crimes, but it is not clear how often the outcomes of gun attacks depend on the ability of offenders to fire more than ten shots (the current magazine capacity limit) without reloading.

Now that eight years have passed since the expiration of the, with sales of "assault weapons" skyrocketing but the number of murders falling, it seems hard to make a case that the expiration of the AWB has had any effect on crime either.

Do military style rifles have legitimate civilian purposes?

The somewhat peculiar rhetorical fall-back which is sometimes executed in the face of this data goes something like this: "Sure, assault weapons may only be used in a small percentage of crimes, but these are guns which have no legitimate civilian purpose, so why not ban them and achieve whatever small reduction in violence that would result?"

This seems like an odd argument in the face of the fact that military style semiautomatic rifles are one of the highest selling types of rifles in the US. With millions of these rifles being owned by US citizens and only a few hundred being used for crimes each year, it seems fairly obvious that there must be legitimate civilian purposes for them. Millions of civilians are choosing to spend $700-$2000 in order to buy these rifles, and very few of them are using the rifles to commit crimes, so whatever they are doing with them would seem to be "legitimate civilian purposes". As I described in more detail in

Part 2, these rifles are actually pretty well suited both to target shooting and to home defense.

Are military style rifles exceptionally "high power" rifles?

One of the other claims that I often see in news stories is that military style rifles such as AR-15s are far more "high powered" rifles than normal civilian rifles.

Coalition to Stop Gun Violence collects a number of quotes from such stories on their "What Law Enforcement Says About Assault Weapons" page:

"We're literally outgunned. You're talking about the kind of firepower that can go through vehicles, through vests, and that can literally go through a house."

...

"These are state-of-the-art weapons ... My firearms experts over here tell me that...no body armor that we have would have saved our officers from these weapons here. I mean, in fact, many of them are capable of slicing through a vehicle. This is just how deadly these weapons are."

...

“[A semiautomatic AK-47 rifle] can lay down a lot of fire in an urban area where there is basically no cover from it. You can conceal yourself from these weapons, but they’ll rip through a car. They’ll rip through a telephone pole. They can rip through just about anything in an urban environment. Everybody understands when they read the morning paper that you have to push as much as you can to get these guns off the street."

It is true that rifle bullets are very powerful and destructive things, often capable of going through walls or piercing the metal body of a car. However, this is the case with all rifle bullets. Indeed, the intermediate size rounds fired by assault rifles are significantly lower power than the rounds typically used by hunters. The 5.56×45mm NATO round fired by the AR-15 packs a force of 1,300 foot-pounds of energy. The 7.62×39mm fired by the AK-47 is slightly more powerful at 1,500 foot-pounds. However, the .308 Winchester, a common hunting cartridge, is far more powerful than either one at 2,600 foot-pounds. Every common hunting cartridge is more powerful than those used by military assault rifles. The suggestion that "assault weapons" fire unusually high powered rounds compared to standard rifles is directly contrary to the very purpose of the shift from battle rifles to assault rifles after World War II, which was to move to a lower power (and thus lower recoil) cartridge that would be easier for soldiers to shoot.

What perhaps gives rise to this confusion is that "assault weapon" rounds pack far more force than standard pistol rounds. For instance, the 9mm Luger round (which the ATF reports is the most common caliber of pistols traced by police in connection with crimes -- and which is also the caliber of pistol most often carried by police themselves) carries a force of only 400 foot-pounds, a little less than a third of that of the AR-15's 5.56×45mm NATO.

Is there a legitimate purpose to "high capacity magazines"?

Magazine size is perhaps the number one area in which new gun control legislation is likely to focus. The 1994 AWB banned the manufacture and importation of magazines holding more than ten rounds for any type of gun with a removable magazine. This had the largest effect on semiautomatic pistols. Most pistols made in the last 20 years hold over a dozen rounds in their standard magazine. (This isn't because the guns are particularly "high capacity", it's just the number that fit in a magazine the same length as the pistol's grip.) Military style rifles also often came with a larger magazine holding 20-30 rounds.

Gun control proponents point out that there are very few situations in which a civilian would need to have a magazine holding more than ten rounds of ammunition. Hunters usually only get one good shot at an animal. Target shooting is usually done in sets of 5 or 10 shots. Very few self defense situations require firing more than ten shots.

However, at the same time, very few crimes involve the firing of large numbers of shots either. The National Institute of Justice study on the AWB reported that only 3% of instances of gun violence involved the firing of more than ten shots -- though those 3% did account for 5% of gunshot injuries, a slightly disproportionate share.

Gun rights advocates respond with two fairly indisputable points: To the person intent on firing a lot of shots in the commission of a crime, carrying extra loaded magazines is easy and changing magazines is incredibly fast. With no particular training it takes about a second to drop an empty magazine and put in a new one. Further, given that there are already, by government estimates, 20-30 million magazines holding more than ten rounds in current circulation, even if the manufacture of more were banned, there are so many already available that the ban would do little other than increase the cost. An sort of buy-back or confiscation program would be very difficult to enforce simply because of the huge number of magazines in circulation. As such, it seems very hard to imagine than any ban of the manufacture of new magazines holding more than ten rounds would do anything other than annoy gun owners -- something which at times seems to be considered an end unto itself among gun control advocates.

Summing up: In the face of terrible crimes, there is a strong desire on the part of civil society to "do something". In the coming weeks and months we will see that instinct playing itself out in full force. An attempt to ban or regulate "assault weapons" is likely to be one of the centerpieces of this attempt to do something. However, for all their black and angular aesthetic, "assault weapons" are not different in function than other common rifles. They substitute metal stocks and grips for wood, and they sometimes feature military style features that have little relevance to civilian use (lugs to which a bayonet can be attached, flash suppressors, etc.) but these features do not make them more dangerous. Indeed, the lighter weight cartridges which they share with the military assault rifles which are their technological ancestors are actually significantly less powerful than the standard hunting cartridges fired by most "normal" civilian rifles. The rifles labeled as "assault weapons" are owned by millions of law abiding citizens, and they are very rarely used in crimes. The urge to ban or regulate them is an urge to put appearances over substance.

|

I don't own an "assault weapon", indeed I've never shot one.

But I would like to own one of these someday if they're still legal:

The M1A, civilian version of the M14, the last US battle rifle. While

I've come to appreciate the AR-15 a lot more while researching these

posts, I"m a wooden stock and .30 cartridge kind of guy.

|

Previous posts:

Assault Weapons Part 1: Battle Rifle to Assault Rifle

Assault Weapons Part 2: Assault Rifles vs. "Assault Weapons"

.JPG)

.JPG)