As is perhaps obvious, I've been spending a fair amount of time looking at data about the coronavirus pandemic. One of the questions that I've seen is: Why is it that the number of new cases and new deaths isn't trending down more now that seem to have peaked in the US and in other countries?

As we've heard about the COVID-19 outbreak, we've seen a lot of charts with curves on them.

Here's the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) prediction of how many deaths we might experience which was released back on April 1st. The model projected a total of 90,000 deaths in the US with a trend that looked like this:

Note that the estimate for peak deaths per day was not far off from what we've seen thus far. We saw 2,631 deaths reported on April 15th, the second highest to date, with the highest being April 21 at 2,683:

(Source:

worldometers.info )

What's different from the IHME chart, however, is that instead of heaving a clear peak and then falling off steeply, the US trend seems to be just continuing. We can see a clear precedent for this behavior in the reported death trend from Italy, which saw its outbreak get big before that in the US did:

That's clearly a more lopsided curve than the one which the IHME projected. If I were to eyeball their curve, one month after peak, the daily death toll should be around 25% of the peak death toll. However, Italy is now one month past their peak and their daily numbers are now coming in in the mid 400s, when their peak was at 900.

One theory I've heard put forth for this is that all around the world countries are now taking very aggressive approaches to classifying deaths, marking down anyone who might have been infected with the virus at some point as dying of it, and thus that now an increasing percentage of total deaths are being classified as coronavirus deaths. This theory would suggest that there was a symmetrical curve of deaths due to the virus, but the lopsided trend we're seeing now is the result a misclassification which is making the total death toll larger than it is.

(Side note: Joseph Moore, the author of the above linked blog Yard Sale of the Mind holds that in fact

we're not really seeing any "excess deaths" due to COVID-19, as the people dying all would have died soon anyway. I think this is false and that the deaths in the US and elsewhere will be clearly visible in overall death data for the year once that becomes available.

Since I think it's important to put one's credibility on the line when making statements like this, I'll lay out in a separate post my commitment to report back in January 2021, examine the data, and either rhetorically eat my hat or show clearly that this was in fact a serious matter causing a death toll in the US of over 75,000, at which point I'll invite Joseph Moore to rhetorically consume a hat of his own.)

I think the trend we're seeing is instead the result of the amount of disease suppression we've achieved using social distancing: enough to start decreasing the number of new cases, but only barely.

Why did we expect a curve that peaked and then decreased quickly? Because that's what China showed for their initial outbreak. The Chinese data is messy, but if I download the Chinese data from the

John Hopkins data repository and chart out the death trend for Hubei province, with a five day average to smooth out its extreme choppiness, I get this:

That's a pretty symmetrical trend. However, two things are worth keeping in mind. First, once the Chinese got serious, they started quarantining sick people in a very, very aggressive way. They also started tracing down all the people each sick person had been in contact with, testing them, and quarantining them. In the US we have not taken this aggressive approach. Part of this is because we hold a lot tighter to our civil liberties than the Chinese government (which is good though it's perhaps worth asking whether some of our hesitation to use more aggressive quarantine procedures is just that it's been a really long time since the West has dealt with a serious infectious disease outbreak and the right balance between quarantine and civil liberties has faded a bit in our cultural memory.) Another factor may be that the Chinese data is not wholly accurate, but since I can't really judge that one way or the other I'll leave that alone.

So my rough theory was: the social distancing measures we're taking with lots of people staying home as much as they can, large gatherings banned, etc. are having a significant effect, but rather than decisively "crushing the curve" they're just kind of gently bending it, giving us that very lopsided trend we're seeing both in Italy (and Spain and France) and so far in the US.

To try to show that the kind of effect I think is going on could produce trends such as we are seeing, I decided to create a simplistic pandemic model and put some different assumptions through it. (When I say simplistic, I mean "in Excel" so we're talking very basic. But

you can view the file here if you want to check my equations.)

In the model, I set up a population of one million and introduced twenty people with a pandemic virus into it. Each person in Simland has contact with an average of 20 other people each day. The contagiousness of the virus is such that each person who is infected has a 1.2% chance of passing the virus to any given person he or she meets. The infection lasts ten days. After ten days, the person either dies (0.5% chance of death) or recovers. People who have recovered are immune to the disease. This means that as more and more of the population is exposed to the virus, the chances of passing it on go down, because a smaller and smaller percentage of the infected person's daily contacts are unexposed. (Note, the chance of passing on the disease, number of contacts, and period of sickness were all made up. I made my disease last only ten days so I could have a shorter model period without scrolling through more than 200 days. I didn't account for people having splintered social networks or families, I just used one big population pool. So this is a very simple model, but the basic ideas of transmission work. And I did work a number of scenarios so I could come up with a model disease which seemed to have some similarities with what we're saying about the coronavirus.)

First I just let the disease rip through my population. Within just over 100 days almost 90% of the population got the disease, and then the population hit herd immunity and the infection rate dropped to a nominal four new infections a day with the remaining ~10% of the population staying healthy. The death and infection curves were entirely symmetrical and the total deaths were a bit over 0.4% of the total population (4,395 deaths out of 1 million people).

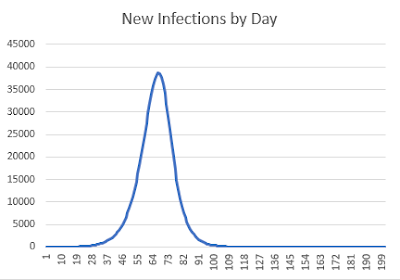

Then I introduced social distancing, starting on Day 35 (at which point almost 5,000 people were infected and seven had died) Over a ten day period, I had my Simlanders reduce their number of daily contacts from twenty to eight. This resulted in a trend in new infections (and ten days later, a mirror trend in new deaths) that was a lopsided curve that may look a bit familiar. (I trimmed this chart to 88 days so you can see the "current" period more clearly.)

As you can see, the number of new infections is going down after a noisy period of adjustment, but it's a long slow reduction. At the two hundred day mark, there are still almost 150 people a day getting the infection. Just under 10% of the population has been infected at some point, and just under 500 people have died. So the social distancing has massively reduced the infections (from 900,000 to under 100,000) and the deaths (from 4,395 to 472). However, the problem is that my Simlanders are still doing their social distancing half a year after they began.

What if the Simlanders decide to get really tough on social distancing? If they do a final crackdown to only four contacts a day, you get a symmetrical curve. However, unless they can make sure that no infected person comes in contact with any uninfected person, the disease doesn't fully wipe out. This curve looks like it goes to zero, but there's actually a small number of daily cases still going. At day 200 a total of 29,644 have ever been sick and 147 have died.

But unless they really can totally quarantine the sick people (resulting in zeroing out the transmission) if they relax their social distancing, they immediately have another big wave. Here's what happens if after cutting their average daily contacts from 20 to 8, and seeing good results, the Simlanders decide to reopen their country on Day 80 and their average daily contacts go back up to 12.

As you can see, as soon as they open up again, the virus starts spreading like crazy again. At day 200 they've had a total of 528,760 people get the virus and 2,617 have died. Short of a vaccine or a treatment, or finding and quarantining all their sick people so that they do not pass it on to anyone else, reopening causes a new outbreak.

However, it's interesting to note that if even after re-opening they have somewhat fewer average contacts per day (12 rather than 20) the disease will level off at a lower level than it would with more contacts. In the original unconstrained model with each Simlander having an average of 20 contacts a day, nearly 90% of the population got the virus and 0.44% of the population died. If when they reopen they do so with a lower number of average contacts a day, only about 50% contract the virus and 0.26% die. So if the Simlanders are unable to quarantine all the sick people and thus wipe the virus out (and knowing that they can't remain in "lockdown" forever) their next best shot is to do a return to "normal" that still reduces the opportunities for spread. They'll lose a lot more people than if they could isolate and eradicate the virus, but they'll save a lot of lives versus a scenario in which they do nothing.

Since this is a purely numbers driven simulation, I can't provide any insight into what the "right" level of sustainable social distancing would be. But at least with this kind of simplistic modeling (and short of having a treatment or vaccine show up) these seem like the two options that would be available.