Friends, it has been a longer time than I like to contemplate, but this trilogy remains one of the major priorities of my artistic life. So when my wife and I managed to take a two day getaway for my birthday over last weekend, which served as a sort of mini writers' retreat, I gratefully took the time to finish this chapter. I hope you enjoy it. It will certainly not be so long before I post another.

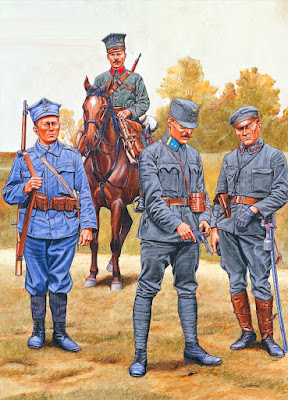

In Chapter 8 we return to Jozef, and we meet a cavalry regiment of the Polish Legion. They're a historically fascinating group, whose founder, Joseph Pilsudski became the father of independent Poland. But I'll let the chapter introduce them to you properly.

Klimontów, Galicia. June 28nd, 1915. It was a distance of less than thirty kilometers from Sandomierz where Jozef’s regiment was stationed -- his former regiment as the orders in his uniform pocket made clear -- to Klimontów where the 1st Cavalry Regiment of the Polish Legion was recovering from a recent engagement. There was no military train available, and Jozef was humiliatingly unable to make the journey on horseback because his mount belonged to the Uhlan regiment. So with his orders in hand and his cavalry spurs jingled on his boots, he was required to stand in line behind two old women carrying chickens in wicker baskets, show his orders to the ticket-master at the Sandomierz train station, and receive a second class ticket (the local train offered no first class) on the slow train to his destination.

The one second class carriage was comfortingly empty; his two companions were a middle aged businessman in a bowler hat, who spent the entire time reading a newspaper printed indecipherably in Slovene, and an elderly Jewish woman dressed all in black who snored softly despite the hardness of the leather-upholstered seats.

Even with the frequent stops of a local train, within two hours the train pulled into Klimontów and Jozef stepped out onto the railway platform. The town was small, consisting of little more than a single square with shop fronts and houses surrounding a fountain. A little beyond, loomed bronze domes of St. Jozefa.

The men of the 1st Cavalry Regiment of the Legion might not outnumber the town’s residents, but they were certainly prominent. As soon as he stepped into the street Jozef saw men in field grey uniforms like his own, but with the distinctive, square-topped czapka helmet of the Polish Uhlans. Some sat at cafe tables or lounged outside shops, others walked singly or in groups. All had the casual aire of men on leave. There was no immediately obvious center of activity, no headquarters building marked out by the runners and orderlies hurrying in and out of it.

Nor did anyone immediately approach Jozef as someone out of place, even though his Austrian Uhlan’s helmet, set him apart as clearly from another regiment. After hesitating and looking about for several moments, Jozef approached a group of three men seated outside a cafe. The jumble of beer and wine glasses told that they had been at the table for some time. One had taken off his uniform tunic and rolled up the sleeves of his shirt against the heat of the day, as he sat talking with his companions and rapidly dealing out hands of some solitaire card game on the table before him.

“Where can I find the regimental headquarters?” Jozef asked, counting on the leutnant stars on his collar tabs to make clear his right to ask a peremptory question of these men whose plain collars marked them as rank and file troopers.

By rights, they should have come immediately to attention before even answering his question. They did not do this. One of the men inclined his head to the card player, as if to defer the question to him. The other fixed Jozef with a commanding eye and asked, “Which is it? Is Kandinsky a genius or an enemy of the beautiful?”

“Who?” asked Jozef.

“Oh, God!” cried the other trooper.

“I didn’t address the question of theology,” replied the first, turning on his companion. “Nor do I admit that it has any bearing on artistic expression.”

“The artistic sense is an expression of culture,” replied the second. “And culture is the expression of the people, and the organizing principle of the people is politics. Yet over politics stands the ultimate purpose of the people, and that is theology. So to the extent that art is cultural, it is political, and the end of the political is God.”

“You are drunk in the presence of an officer, and that is political,” replied the first trooper. “Sir,” he added, addressing himself to Jozef, “If you’re seeking headquarters the leutnant can help you.” He indicated the man in his shirt sleeves.

The card player ignored Jozef for a moment more as he rapidly laid down cards to complete the formation he had been creating. Then he slapped down a two of acorns with a triumphant “Aha!” and scooped up the entire deck of cards into a pile which he tapped neatly into place.

“Yes?” the card player asked. “Can I help you?”

“You are an officer, sir?” Jozef asked, with a formality that hinted skepticism.

The card player shrugged into his tunic and began buttoning it up, making his leutnant’s stars visible in the process.

“Leutnant Zelewski,” he replied, rising to his feet. “And whom do I have the pleasure to meet, sir?”

“Leutnant von Revay, 7th Imperial Royal Uhlans. I have orders to report to Oberst Gorski.”

“Well, I’d better escort you to headquarters then. Come on.”

He started down the cobbled street and Jozef fell into step next to him. The leutnant’s walk was casual, without the rigid posture most career officers had taken on through long training, and to sit drinking, his tunic off, with common troopers at a cafe would be unimaginable in a normal regiment, no matter how hot the day.

“What do you make of the tone of our regiment?” Leutnant Zelewski asked.

Jozef hesitated. The question alone suggested rather too much insight into the silent judgment he had rendered upon the regiment.

“One thing you’ll find,” Zelewski continued, “is that the backgrounds of our troopers are a little more wide ranging than the standard cut. Dudek, for instance, is a professor of political philosophy, while Bak, as perhaps you could tell, writes artistic criticism.”

“And you?” asked Jozef, wondering if all the Polish Legionnaires came from such academic backgrounds.

“Bank robber,” replied Zelewski. He let the phrase drop with conscious showmanship, and after pausing for reaction added, “And essayist. Political agitator.”