For several weeks after President Biden's disastrous debate performance, it looked like the Democrats might, through sheer inertia, end up running an election with a candidate who was clearly not mentally fit to run a campaign, much less a country. But in the end, the party leadership won, and Biden reluctantly announced that he would not seek reelection. Over 48 hours the party rapidly converged on a new consensus that rather than have any kind of new primary process or open convention, everyone would endorse Vice President Harris, and now here we are with a Trump/Harris race instead of a Trump/Biden race.

One line that some writers have tried is: In an era of weakened institutions, the Democratic Party still functions. They were able to push Biden out when it became clear that he was too debilitated to win, thus showing themselves a more functional organization than the Republican Party, which went from assuming in January 2021 that Trump was over in public life to having him nominated, yet again, to the chagrin of many careerists inside the GOP.

I think, however, there's a more interesting contrast to draw, because both parties are broken, though in very different ways. In both cases, there is increasing estrangement between the traditional party base and the elites (elected officials, professional operatives, and staff.) Both parties are undergoing a re-alignment. But in the case of the Republicans, it is the base that is running away with the party and losing their elites while with the Democrats the elites are changing the party and in danger of losing or fracturing the base.

There is an extent to which the Trumpification of the GOP has been a unique phenomenon. I do not think most commentators give sufficient credit for Trump's success to the fact he was already a famous businessman and reality TV star before he came down the golden escalator to announce his bid for the GOP nomination.

But that takeover was made possible by a long term dissatisfaction with the party elites on the part of the base. The long term dynamic in the GOP was that the staffers and operatives and elected officials were to the left of the base, particularly on cultural issues.

Sure, Republican elites liked lowering taxes and decreasing regulation. But most of them like the idea of abortion still being quietly available if some respectable girl got pregnant too early in life. They thought it was fine if two men got married. They went to Church but thought of it more like the Rotary Club than a means of salvation. They found gun rights activists a bit embarrassing. At root, they had mostly gone to the same colleges and law schools as their opponents across the aisle, and they had more culturally in common with elite Democrats than they did with their base of voters.

Some things worked. The judicial philosophy endorsed by the Federalist Society of reading laws to mean what they say (and not what the judges thought they ought to say) would eventually lead to the overturn to Roe v. Wade and of some of the country's most restrictive gun laws.

But the GOP base knew that it was not respected by its elites. Sometimes it came out egregiously, as with Romney's pathetic attempt to portray himself as "severely conservative" when his actual record was of a Harvard trained private equity executive who had governed as a decidedly liberal Republican during his time as governor of Massachusetts.

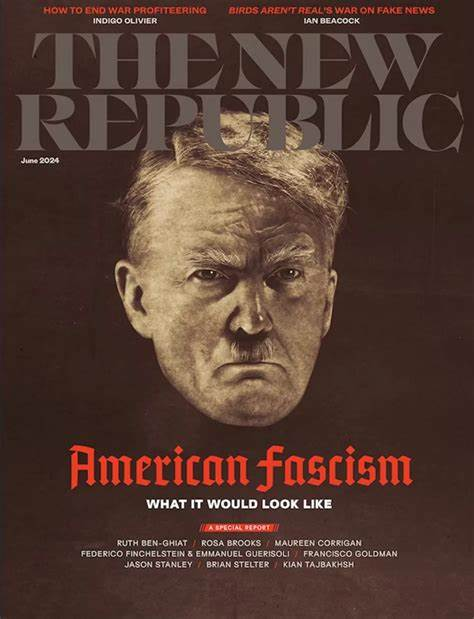

This simmering dislike and distrust of the party elites by the base made it easier for some people to talk themselves into the idea that Trump (also hated by the party elites) was a good tool to use against them. For these Republicans, Trump became a protest vote not just against the Democrats (who happily labeled any GOP nominee including Mitt Romney and John McCain as a crypto-fascist radical) but against the party elites themselves.

The fact that so many party elites didn't want to work with or for Trump ended up letting further-right staffers (including some very good Christian conservatives) get more prominence in the White House during Trump's first time. So in one sense, the fact that the base nominated and then elected a candidate the elites hated (because they considered him ignorant, embarrassing, and ill-suited to governing) did actually lead to a fairly conservative administration, despite the fact that Trump himself clearly does not care much about most conservative issues (as shown by the new GOP platform pushed through by Trump which stakes down "moderate" positions on keeping abortion and same sex marriage legal.)

And now, of course, there are the MAGA ideology grifters, busy inventing some sort of program to peddle as the old elites are squeezed out. But in general, there's a policy and expertise vacuum now in the GOP due to the base's embrace of Trump.

On the Democratic side, as in the pre-Trump GOP, the elites are to the left of the base. But while with the old GOP this mean that the elites were near the center of the ideological spectrum while the base was off to the right, for the Democrats this means that professional Democrats are way off on the far left of the country's range.

Given the way that the left has entrenched itself in academia and the media, they feel like they are right in the middle of the spectrum, because they are very much in tune with the elite colleges they went to, the elite media that cover them, and other Democratic activists. But compared to the Democratic base which has in recent decades consisted of Blacks and other racial minorities, union workers, and lower income families, agenda items like sex changes for kids are decidedly out of the mainstream.

So far, however, the elites seem to be holding on in the Democratic party. Their roots in academia and upper middle class meritocratic culture seem to cause certain dysfunctions, in particular the extreme representationalism and "it's my turn now" dynamics which have controlled recent primary processes. Most Democrats seem to agree that Kamala Harris is not the most talented politician among the crop of governors and senators who would normally be considered. However, the value system of Democratic elites is such that passing over a Black woman when it is "her turn" due to having been the Vice President (a job which, in turn, she got because Biden had pledged to pick a Black woman and she was the candidate available who fit that description) is virtually impossible.

For the very online, mostly female, upper middle-class group which has increasingly become the noisy and dominant sector of the Democratic coalition online, having Kamala Harris as their candidate is a meme come true. For the rest of the party, it's at least a huge relief to have a candidate who is lower on the actuarial tables and capable of stringing several sentences together competently.

This cautious, highly managed Democratic party, deeply convinced that they are the smartest and best people to be running the country if only the voters would shut up and get in line, is the one which just brought us the unnerving spectacle of a president whom people are now willing to admit was not fully functional for the majority of his term as president.

At first, when news of this broke, people were actually willing to get on the air and argue, "Sure, our guy is stumbling and mumbling and clearly not able to govern, but it's not really about him, it's about the whole team." Translation: Just vote Democrat and let us figure out who is going to actually be in charge.

Some on the Right have tried to argue that selecting Harris as the nominee after all the primary elections are over is a violation of democracy. Perhaps in some procedural sense it is, though it's worth noting that the modern primary system wasn't put in place until the 1970s.

While one can see why they'd prefer to run against Biden, I think their outrage is misplaced. It's not the party changing its selection process to swap in Harris which is the violation of the democratic elements of our republic. The massive problem here is that Biden was not much up to the job of governing when elected and became less able to govern through his four years, up to the point where it's pretty clearly not Biden running things. And yet, rather than admitting the president was no longer capable and letting the vice president succeed him in office, the administration chose to cover this up and let unelected staff increasingly run the country. Not only were they not elected to that task, but they no longer were held in check by a chief executive who was up to determining they were out of line and firing them. And despite the fact this was clearly something at least tacitly known by many among the government, they were fine to prevent a real primary from taking place in hopes they could coast to a second term -- until they got caught by the debate.

This is not how our system is supposed to work, but for portions of the Democratic base, this was just fine. Is it enough of the base of the Democratic coalition to hold together? That remains to be seen. Over the last eight years the share of unmarried college educated women voting Democrat has skyrocketed, while at the same time the working class (particularly men -- even some Black and Hispanic ones) has been drifting towards the GOP. Who would have imagined twenty years ago that the head of the Teamsters Union would be speaking at the Republican convention rather than the Democratic one.

Where we sit is that we have one party where the base has turned out to re-nominate a candidate who denied the results of the 2020 election and tried to hold on despite having lost. (Though he did so incompetently enough I don't think there was much danger of his succeeding.) And the other party which was quite happy to turn the running of the country over to unelected staff while concealing that the elected president was effectively unable to govern.

It's not a good spot to be, and both parties seem determined to go further in this direction until something pulls them back.