Friday, March 31, 2006

The youth of today

Every now and then we wonder, "Are we doing something wrong? Are everyone else's kids behaved like this?" So, here's your chance to let the world know about your children. If you have a story of misbehavior, disaster, testing -- anything that makes you want to tear out your hair -- feel free to share it here. If you have a good strategy for coping with the young miscreant, post that too. If your child has learned how to unlatch your fridge, I really want to hear from you. And if you can't leave your children alone to go to the bathroom without some sort of massive destruction taking place, let's just forget the blog and go to lunch together.

Help me out, parents! Let us know that we're not the only ones!

Pushing the Boundaries

Maggie's point is an interesting one: For many intellectuals, the next logical step in any given progression is always a point of intense interest. Thus, the NY Times elites, having some time ago settled on the idea that many 'non standard family' configurations such as gay marriage make sense, now find it intriguing that polygamy may also be a viable lifestyle. This doesn't necessarily mean that they are actually in favor of polygamy. (And the Mormon fundamentalist polygamists they're interviewing probably aren't in favor of many of the cultural innovations that NY elites support.) But they do find the idea that polygamy might be another valid lifestyle interesting.

However, cultural standards are essentially that set of standards which no one thinks it makes sense to question. In 1900, there was a cultural standard against unwed motherhood because almost no one was willing to even imagine it as a moral or cultural option. By the '60s and '70s, voluntary single motherhood was becoming imaginable, even though most people tried very hard to avoid it. However, a generation after it became imaginable, it now isn't considered all that surprising for a woman to intentionally have a child out of wedlock.

Gay marriage as a lifestyle first become imaginable in the '80s. Much before that, not only was it not imagined by the culture as a whole, but so far as one can tell it wasn't even particularly desired by active homosexuals themselves, who celebrated their freedom from straight relationship standards.

Now the idea of polygamous or multi-tiered family relationships seems intriguing to some cultural elites. And without any generally accepted cultural standards of what a marriage or family is at an essential level (other than 'a relationship of people who love each other') there is no reason why the idea of 'multi-marriage' might not also become unsurprising in certain segments of society.

Which goes to show, you need to be careful what ideas you play with.

Thursday, March 30, 2006

The High Notes

Castration before puberty (or in its early stages) prevents the boy's larynx from being fully transformed by the normal physiological effects of puberty. As a result, the vocal range of prepubescence (shared by boys and girls) is largely retained, and the voice develops into adulthood in a unique way. As the castrato's body grows (especially in lung capacity and muscular strength), and as his musical training and maturity increase, his voice develops a range, power and flexibility quite different from the singing voice of the adult female, but also markedly different from the higher vocal ranges of the uncastrated adult male. (From Wikipedia.)This BBC article includes a 1902 sound clip of the only castrati ever to be recorded: Alessandro Moreschi, who directed the Sistine Chapel Choir until 1913. (Moreschi also recorded an Ave Maria.) His voice is odd and freaky and gives me the shivers, frankly -- I can't really be comfortable listening to it, knowing how the bizarre vocal quality was obtained.

H/T Whispers in the Loggia

If You're Not Outraged...

It turned out most of the commenters were liberals absolutely furious over the title of the book and the except from the jacket flap printed on Amazon. It's one thing to disagree over abortion, seemed to the be general sentiment, but writing a book titled "The Party of Death" debased political discourse and was unnecessarily inflammatory in an already divided country.

Now goodness knows, I can see worrying that our national house is becoming too divided to stand. But at the same time, those who take the "why are you pro-lifers so angry?" tack always strike me as vaguely clueless. I had a coworker a few years back who was big into politics. In most economic issues, he was very slightly on the Republican side of moderate, but on social issues he was a definite liberal. "Why don't those people just take a year off?" he wanted would demand every so often. "I'm tired of every election being sex, sex, sex, abortion, abortion, abortion. How about if everyone just agrees not to talk about the issue for a year?"

But this kind of thinking only makes sense if you either believe that abortion is no big deal, or that it's absolutely impossible for the political process to achieve any progress on the issue one way or the other. Otherwise, life advocates will never 'shut up' because being silent in the face of over a million deaths each year is impossible. And abortion advocates will never 'shut up' because if abortion is just another medical procedure which stands to make millions of women happier and healthier, then restricting it is clearly just plain cruel.

On the one hand, I do often wish that our political arena didn't so much resemble a cultural cage match. On the other hand, when we disagree on such basic and important topics, one can't expect people to 'shut up' on them unless one expects people to abandon their principles and be quiet in the face of a major perceived injustice.

Coming Soon...

History Comes Knocking

The contents consisted of a German K98 Mauser and a Russian 91/30 Mosin Nagant rifle, both manufactured in 1942 (the Russian one I'm sure on, the date is stamped on it, but the German one might have been manufactured in late 1941, I'm still researching) -- and since the Mauser is one of the few made with an enlarged trigger guard to allow a soldier wearing gloves to fire it, it's probably a good bet that both were headed for the Eastern Front around the time of Stalingrad.

They need some good cleaning up, but both appear to be in pretty good condition. The girls are thrilled -- perhaps a little two thrilled as the first thing they asked me early this morning was: "Where are your guns, Daddy? Can we see them again?"

I've informed girls that guns are locked away until the weekend when Daddy will work on cleaning them. Good to seem them showing and interest, but there's a definite limit how much interest in guns a 2.5 and 3.5 year old should have...

I'm thinking the 1-2 year goal is to get one each of the combat rifles issued by the major powers in the European theatre in WW2, which means I still need an Enfield and an M1 Garand. We shall see.

Wednesday, March 29, 2006

The Dirt on my Floor

1. The girls broke an egg on the kitchen floor (a farm-fresh egg at that) and tried to sweep it.

2. The girls, while washing their hands in the downstairs bathroom, decided to fill containers with water and ended up soaking several sections of the living room carpet.

3. The girls wanted a snack and so fetched themselves Cheerios, which they ate on the wet area of the carpet.

That wood floor is sounding real good to me about now. As does thirty days of solitary confinement with a good book and an unlimited supply of tea.

Lex Orandi, Lex Credendi

As often seems to happen, the comment thread eventually sinks into an Orthodox vs. Catholic sand kicking contest over whether current problems with Catholic liturgy prove that there must be something much deeper wrong with the Church. One often hears the same sentiment from traditionalists of one stripe or another, who point out that even poorly educated Catholics could pick up certain basic elements of theology and piety simply by experiencing the Tridentine liturgy, which the Novus Ordo liturgy (at least as celebrated in the average suburban parish) is much less overtly supernatural in orientation, and so teaches less. Lex orandi, lex credendi.

Now, I can't exactly be classified as a traditionalist per se. I've only attended 10-20 Latin masses in my life. I somewhat prefer the Latin Novus Ordo high mass to the Tridentine. The sign of peace doesn't give me fits (though between the ages of four and six I refused to give or accept the sign of peace because I figured that if Jesus gave me peace I'd never have adventures like in Star Wars), I receive communion under both species when given the chance, and I often mess up Latin responses in mass by using the classical Latin pronunciation rather than the ecclesiastical (or nasty, modern, barbaric pronunciation, as we enthusiastic classics students call it). But I do firmly believe that mass should be firmly vertically focused. We should experience, both architecturally as we enter the church building and liturgically though the ritual of the mass, a profound sense of otherness -- that we area treading on ground that is only half of our world, and experiencing something that is not fully within our comprehension. And this is certainly well within the powers of the Novus Ordo when celebrated properly. Back before MrsDarwin and I were students traveling Europe on the cheap, we attended Easter vigil at the Brompton Oratory in London. (outside, sanctuary)

In this sense, liturgy is very important in fostering belief. With our modern issues in catechesis, the mass may be pretty much all the instruction that many Catholics get in their faith. However, lex orandi, lex credendi is not all there is to the story by a long shot. While the Brompton Oratory is a model of both liturgical and pastoral success, we stopped in at many cathedrals throughout the continent where beautiful masses were being celebrated in beautiful cathedrals, with almost no congregation except a few gawking tourists. Perhaps they put on a show for the tourists, and actual parish liturgies in Europe are more disappointing. But at least from what we saw I would say that the liturgies we attended there were far superior to most of what you can find in the US. We often hear, however, that the church in Europe is in many ways in far worse shape than the church here. Clearly, it takes more than the availability of good liturgy and beautiful architecture to create a thriving laity.

Still, I find myself much in agreement with what Bearing Blog said the other day, about feeling a certain sense of anger that the two generations before my own saw fit to throw out much of the Catholic culture they inherited, leaving those of us who come after to try to rebuild from the scattered stones.

Tuesday, March 28, 2006

The Dirt on Carpet

A week or so ago, I found myself vacuuming the stairs with the hand-held vac, and so getting an up close and personal look at the carpet. "This carpet is repulsive!" I thought. "What kinds of vile life-forms might be living where the vacuum can't reach?" Well, DarwinCatholic exists so that you, the reader, don't have to do this kind of research. Here's what I came up with after a brief Google search of "carpet allergen asthma":

A BBC report gives us the lowdown on dust mites:

Dr Warner said up to 100,000 dust mites can live in just one square metre of carpet alone.

The droppings of these tiny creatures are believed to stimulate asthma and other allergic responses.

Carpets also harbour material from pets such as cats and dogs which is also thought to be a leading cause of allergy.

Dr Warner told the BBC: "House dust mites like to live in dark and damp environments and we find a lot of them at the base of the carpet.

"When you consider that each one of them produces 20 faecal particles every day, and that is where we find the allergen then there are an awful lot in a house full of fitted carpets."

Here's a little Q & A from the Carpet and Rug Institute FAQ Page:

My child has asthma, I want carpet but what do I look for?

CRI is not aware of any published scientific research demonstrating a link between carpet and asthma or allergies. Look for green label carpets and cushions, plan for good ventilation during the installation process and plan for routine vacuuming with a green label vacuum. We are not aware that any particular product is better than any other.I have dust and pollen allergies, I want carpet but how will this affect my allergies?

People that have allergies should vacuum their carpet at least twice a week and have their carpet cleaned the way the manufacturer specifies approximately every 12 to 18 months. Carpet is an asset for allergy sufferers as it traps the dust versus a hard surface where dust lays on top of the surface to be kicked back into our breathing zone. We recommend using a vacuum with good dust containment and performance properties such as those in our green label vacuum program.A article at Care2, an environmental website, recommends against wall-to-wall carpet:

"Wall-to-wall carpets are a sink for dirt, dust mites, molds and pesticide residues. I much prefer smaller washable carpets of natural fiber," says Philip Landrigan, M.D., director of the center for children's environmental health at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. Washing in hot water kills dust mites, microscopic creatures whose plentiful droppings are a top asthma and allergy trigger, Dr. Landrigan explains. Another benefit: you can also regularly clean the floor underneath, defeating dust buildup. Just be sure to put a non-slip pad under area rugs.I was already prejudiced against carpet, but I'm glad to find my suspicions confirmed. In fairness, however, I must note that a doctor in the BBC article stated that beds harbor far more dust mites than carpet. Yeah, but I like my bed! I'd rather get rid of the carpet.

Here's what I really want:

Constructivism and Education

As with many theories, it seems like there is a certain core of truth to this. It is true that our knowledge of the world (there are after all things we can know without reference to the world -- mathematical knowledge, for example) is filtered through our ability to correctly understand what we observe, which in turn is affected by our personal and cultural biases. Yet, the value of this mental construction of the world is the degree of similarity it bears to the real world which does indeed exist outside of us. Focusing on the importance of building one's own model while ignoring its degree of semblance to the real world makes the whole concept of knowledge irrelevant, as this article Fred links to points out:

Accordingly, most constructivists are relativists (although some disclaim it). For relativists there is no truth, only "truth"-truth in quotes-"a rhetorical pat on the back," as one noted relativist philosopher has explained-a compliment accorded that which is agreed to in some community by that community, but no more than that. Hence there is no robust connection between science and some universal, external reality. To a social constructivist,42 in particular, there can be no "knowledge"; there are only knowledges. Not only "Western" science, then, knows the physical world; science is no better a way of knowing it than many other, very different ways of knowing.All in all, it sounds like constructivism has some very useful ideas, but (especially when combined with our current culture's tendency towards relativism and self-esteem worship) can also lead in intellectually destructive directions.

That is the force of the statement that "science is a mental representation constructed by the individual." Outside the individual, in other words, there is no independent reality to which "knowledge" or "truth" corresponds. Knowledge of the world is in each human mind, where it is constructed from prior and current experience. Some constructivists insist that they are not anti-realists-they do not reject reality; only "objectivism" (often misidentified by philosophic amateurs with "positivism"), their label for claims that knowledge can be free of personal and cultural bias. For a serious constructivist, there is no knowledge free of cultural bias. To which, then, the last of these quotations is the appropriate conclusion: that the history of science is no more than "the changing commitments of scientists . . . . [which] forge changes commonly referred to as advances in science." Meaning: there is no real progress toward truth about the physical world. Over the centuries, there have been only changing opinions about it, reached by negotiation and power shifts among contending parties. Scientists just use the term "advances" to label any changes to which they are finally agreed.

Exploring this bizarre amalgam of postmodernism, epistemological relativism, and old learning theory, the astounded layman may well ask, "How can anyone teach natural science under a theory of science so hostile to its purposes, so blind to its practices and achievements?" The full answer is more than "Well . . . they don't teach it," although that is a part of it.

And the number of the day is... Jihad

I am a servant of Allah. I am 22 years old. I was born in Tehran, Iran. My father, mother and older sister immigrated to the United States in 1985 when I was 2 years of age, and I have lived in the United States ever since. ... I have decided to take advantage of my presence on United States soil on Friday, March 3, 2006, to take the lives of as many Americans and American sympathizers as i can in order to punish United States for their immoral actions around the world. In the Qur'an, Allah states that the believing men and women have permission to murder anyone responsible for the killing of other believing men and women. I know that the Qur'an is a legitimate and authoritative holy scripture since it is completely validated by modern science and also mathematically encoded with the number 19 beyond human ability.Belmont links to an Islamic website's explanation of the significance of 19:

The number 19 possesses unique mathematical properties, for example:This kind of thinking sounds strange to modern ears, but similar arguments were not uncommon in the West just a few hundred years ago.

1-It is a prime number , only divides by itself and one.

2-It encompasses the first numeral (1) and the last numeral (9), as if to proclaim God's attribute in 57:3 as the "Alpha and the Omega".

3-Its {numerals} look the same in all languages in the world.The numerals (1) and (9) look very much the same in , for example Arabic and English.

4-It possesses many peculiar mathematical properties. For example, 19 is the sum of the first powers of 9 and 10, and the difference between the second powers of 9 and 10.

5-Number 19 is the numerical value of the word "ONE" in all the scriptural languages, Aramaic, Hebrew, and Arabic. The number 19, therefore proclaims the First commandment in all the scriptures: that there is only ONE GOD.

The word "ONE" "Wahid" in reference to God, in the Quran, is used 19 times. Is it a co-incidence?

The number 19 itself has no power and has no holiness, and can lead you no where. It is the Miracle that is based on this number that has the significance. This significance is explained clearly by God Almighty Himself in 74:30-31.

"Over it is nineteen." " We appointed angels to be guardians of Hell, and we assigned THEIR NUMBER (i.e.19) (1) to disturb the disbelievers. (2) to convince the Christians and Jews (that this is a divine scripture), (3) to strengthen the faith of the faithful, (4)to remove all traces of doubt from the hearts of Christians, Jews, as well as the believers, and (5) to expose those who harbor doubt in their hearts, and the disbelievers; they will say," What did God mean by this allegory ?" God thus sends astray whomever He wills, and guides whomever He wills, None knows the soldiers of your Lord except He. THIS IS A REMINDER FOR THE PEOPLE." 74:30-31

Given the apparent fascination of certain elements of Islam with the number 19, one must wonder: Was it just happenstance that there were 19 hijackers on 9-11, or was that part of the message, to those who could understand it?

Monday, March 27, 2006

NFP in the Local Paper

"A lot of my patients use other (birth control) methods during the fertile time, because the reality is that at the time women most want to have sex — it's difficult to abstain because of the surge in hormones," Ryan says. "It's a biological urge to create babies, and that's the flaw in the thinking of those who advocate abstinence during the fertile time."

Abstinence, it appears, is the Achilles' heel of natural birth control. Contraceptive Technology, a manual for health care providers, says that in "perfect use," natural methods are 91 percent to 99 percent effective — as effective as the pill. But in the real, nonperfect world, natural methods are only 75 percent effective. Most people who teach natural family planning say that reflects the challenge of abstaining from intercourse during risky times.

Ryan says a number of her natural family planning patients have become pregnant, but almost always because the couple ignored signs that the woman was ovulating. McCaslin says the FertilityCare Center sees between five and 10 unplanned pregnancies out of 200 new users each year, but "very rarely do we find one that doesn't have an explanation as to why it occurred."

Mary Cullinane, a nurse practitioner and director of patient services at Planned Parenthood of the Texas Capital Region, says the majority of Planned Parenthood patients who use fertility awareness are educated, interested in natural health, and are in stable relationships with a partner who is willing to abstain. But, she says, she can count on one hand the number of these women she sees in a year.

"Any method that requires a lot of user thought and preparedness, or cooperation from the partner, is going to be less effective than the methods where you don't have to do anything — where you just take a pill every day, or you put an IUD in and it lasts for years, or you get implants in your arm. It takes a lot of motivation, education and cooperation, and not everybody has that in their relationship or their life," she says. (emphasis added)

I foresee new ads:

The Pill! Perfect for the couple who can't be bothered to communicate!

Less talk, more sex! A condom a day keeps discussion at bay!

Give yourself an IOU on committment! Use an IUD!

Or maybe not...

Neighborhood watch

Here's a site that will map out all registered sex offenders near your home. A little house marks the location of your home on the map, and the little colored boxes pinpoint the addresses of the offenders. If you click on the boxes, you get a picture of the person, his address, and his crime.

I'm pleased and relieved to note that the Darwins seem to live in a fairly safe area -- reassuring as I'm about to head out for a walk with the girls.

It's rough to be first

For whatever reason, I was trying to remember what had happened to Laika the other morning. You may have read about her. She was the first dog to make orbit around the earth -- on Nov. 3rd 1957 aboard the Russian Sputnik 2 space capsule.

For whatever reason, I was trying to remember what had happened to Laika the other morning. You may have read about her. She was the first dog to make orbit around the earth -- on Nov. 3rd 1957 aboard the Russian Sputnik 2 space capsule.I thought that I remembered that (in typical Soviet fashion) Laika's trip was a one-way stunt, and she died in space. Looking it up, it seems I was right, though the plan had been to put her down quietly via poisoned food. Unfortunately, the Soviets hadn't yet got space capsule construction figured out very well, and she died a few hours after launch of stress and overheating.

The American Ham the chimp had better luck in January 1961, when he flew in a Mercury space capsule and was returned safely to Earth via parachute and splash landing -- just like the later Mercury astronauts. While in orbit, he performed a number of trained tasks in response to stimuli like blinking lights and negative reinforcement from electrical shocks to his feet. (Now I think about it, negative reinformcement from electrical shocks to the feet might have been useful in reigning in Mercury astronauts from our own species who ended up in Congress...)

Ham lived 22 more years after his flight and is buried at the International Space Hall of Fame in New Mexico.

However, it turns out that Ham had a number of less lucky cousins who get less press coverage. The first American monkey in space was named Albert and flew on a modified V2 rocket in 1948. He suffocated during the flight. Albert 2 (couldn't they come up with a new name if they were going to keep wasting monkeys?) survived his flight on a V2, but died on impact. Albert 3 died when his V2 blew up in flight. And Albert 4 died on impact. (It doesn't say if there was any attempt to have the V2 land differently than its military cousins in WW2.)

Yorick, another monkey, survived his flight on an Aerobee rocket along with 11 mouse crewmates in 1951, but he died two days later. Alas, poor Yorick.

In 1958 a squirrel monkey named Gordo (and nicknamed Old Reliable) successfully flew on a Jupiter rocket. Unfortunately, his vehicle was less reliable and he died as a result of parachute failure on re-entry.

All together, it seems to have been a brutish and short life being a space animal in the 50s. Still, perhaps we have them to thank for having had relatively few human deaths in the early space program.

Saturday, March 25, 2006

Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion

Gould's thesis is that Religion and Science represent separate but equal fields of knowledge which never truly come into conflict because they deal with different issues. He calls his schema NOMA (short for Non-Overlapping Magisteria) and basis the division on the old line that "science tells us how the heavens go, while religion tells us how to get to heaven."

Why does an agnostic scientist tackle this particular topic? Partly out of an honest desire to clear up what Gould sees as a common misunderstanding. Regardless of how others may view his work as a vocal defender of the modern evolutionary synthesis in biology, Gould did not consider himself an enemy of religion. He writes in the introduction about how religion has always fascinated him, partly because he felt that it was a major gap in his upbringing -- his parents having abandoned their Jewish faith to embrace militant atheism. Gould says he believes his parents went to far -- despite the fact that he himself remains an agnostic, he feels that his parents had an irrational hatred of religion (and notes that atheism is as much an act of faith as theism.)

There are some very good things that Gould has to say, and which Christians should be glad to hear someone on the 'other side' acknowledging. Gould makes it clear that no one lives without holding religious beliefs and making religious judgments. He contends that moral/ethical decisions are invariably based upon a form of religious belief, whether that belief is based upon revelation, instinct, or philosophical introspection. In that sense, an atheist relies just as much upon religion as does an orthodox Jew, it is simply that the atheist's religious beliefs are different (that there is no God) and so his conclusions also are different from those of a believer.

Gould clearly lays out the argument that judgments of worth (good, justice, beauty) and moral norms (killing is wrong, charity is good) cannot be the result of 'scientific' thought. Even the most secular person, he says, invariably makes many important decisions about his life based upon religious thought. To this extent, he's saying the same thing as many Christian apologists. We should be glad to hear it coming from him as well.

While questions of ethics and purpose are the domain of religion in Gould's schema, the domain of science is to determine the history and workings of the physical world. So (after first acknowledging that many of Galileo's problems were of his own making) Gould points to the Galileo case as an example of religious authorities violating NOMA by asserting that the Earth must be stationary with the Sun orbiting around it. Gould says it would be a violation of the realm of science for religious authorities to assert that certain things about the world 'must be' regardless of what the evidence suggests. For instance, while generally praising Humani Generis for it's treatment of the evolution question, he raises an eyebrow at the assertion that Catholics must hold that all current humans are descended from a specific man and woman. Gould says he doesn't know enough about Catholic theology to know if this is meant in a primarily theological way, but that if Pius XII was speaking in biological terms, this constitutes a violation of the separation between the magisteria of science and religion. Religion, in his schema, may define what humans should do and what they are in a metaphysical sense, but it cannot say "we know it for a fact that all humans are descended from a specific couple at some point in history".

Here I think Gould's outsider's attempt to address the proper domain of religion falls a bit short. He doesn't seem to understand the relationship between statements about what the world means and what we ought to do in it and more physical or historical statements about the world. Many moral norms are based upon an understanding of what the essence of some thing or action is. For instance, the Church's teaching against birth control is based on the understanding that the marital act is in its essence fertile -- regardless of whether the particular case of marital intercourse at hand is physically likely to result in conception. Thus, the Church does make a statement about physical reality in proclaiming this doctrine. If it were somehow proved totally false that sex had anything to do with reproduction, the Church's prohibition of birth control would be rendered foolish.

The other weak point in Gould's thinking (and certainly an understandable one given where he is coming from) is that he seems to imagine a very simple dichotomy between 'natural' and 'miracle'. Thus, he takes it as a first principle for scientific thinking (and for his division between science and religion) that no major elements of the physical development or workings of the universe are the result of 'miraculous intervention'. Thus, he cites Newton for violating NOMA when he suggested that God might reach in and correct the planets in their paths every so often just to keep them on track.

The Newton example is an easy target, because Newton seems to have thought in the same way as Gould: either something is 'natural' or 'God did it'. It seems to me that a better understanding would be to recognize that if God is (as we believe he is) all powerful, omnipotent, and our creator, that His 'interventions' would be very different from the way that I might reach into a model trail rig and nudge something that wasn't going the way I wanted. In the Catholic tradition we believe that the universe is actively held in existence by God's will. The workings of the universe are, thus, in a certain sense, inside the mind of God. What we see as natural laws are not something outside of God which work along in their merry way until God intervenes. Rather, natural laws are what we are able to see of the rational mind of God as expressed in the workings of His creation. Natural laws remain fixed because God is fixed. Thus, the reason that science can proceed with a certain confidence that the planets will not go off track and need to be nudged back into position through a miracle is that the laws of physics which control the movement of the planets are already themselves an expression of God's will for how matter should work and interact.

Incidentally, it's within this perspective that it seems to me wrongheaded to insist that there must somewhere be scientifically detectable signs of God's 'design' where He reached in and helped something reach a form that mere laws of nature could not have achieved. God created and maintains the laws of nature. They're not some lesser thing that he occasionally infuses strokes of brilliance into. Nor is a rock or a pool of water any less 'designed' because of its simplicity than the most complex features of the human body. God's stamp is upon it all equally, not just the cool bits.

Friday, March 24, 2006

What about SOCIALIZATION?

And over the years I've decided that it's that same genuine concern that prompts a lot of the negative responses people have about homeschooling. I just wish these folks would stop and think about what is REALLY bothering them, what their concerns really are. Usually, their objections are based on assumptions they have never seriously analyzed.

Like this one. If I had a nickel for every time someone has said to me, "But you're not a scientist. How are you going to teach them biology, chemistry, trigonometry?" I could pay my mortgage and have change left over. I always answer, quite seriously, "Well, I took those classes in high school. Didn't you?"

"Of course," the skeptic will say, "but it's not like I REMEMBER any of it."

This cracks me up. Sometimes I'll say, if I'm feeling snarky, "Then surely I can do a better job than your teacher did!"

I knew a guy who used to say, when asked about socialization, "But we don't want to be socialists!"

I was worrying the other night that I wasn't doing enough "educational" stuff with Noogs. The only structured activity we do is her reading lesson, which only takes about twenty minutes and isn't necessarily daily. Then two things struck me:

1) Noogs isn't even four yet; and

2) So?

I'm not trying to conform to some abstruse government standard of grading and testability, so instantly my life is easier than that of a teacher in a public school. The only demanding parents I have to please are myself and Darwin, and I don't call myself up to complain. And as Noogs is already learning to read, we seem to be doing things well so far. The girls can count and sing the alphabet song and memorize stories. I never planned to send them to preschool, and I don't think that they're behind the curve for not having gone. Besides, what could be more educational than having a new baby around the house?

I don't think anyone has ever asked me, now or when I was being homeschooled, about socialization. I wonder what the new buzzword question for homeschoolers is?

Since it's too early for you to be drunk for the weekend...

The report said Maurice Peeters, a Belgian farmer, noticed there was something different about the lamb born on his ranch over the weekend."The vet immediately put his hand on it, and asked me if I'd seen it," Peeters told reporters who visited his home. "I said I'd seen it and I said I'd seen it has way too many legs."Pretty funky, huh? H/T Jimmy Akin.

The lamb is healthy, but cannot walk, according to the report.Peeters said he'll wait for the lamb to get stronger before he'll try to amputate two of the legs next week."The front two legs have to go, this one is a good one," Peeters said.

You know your child has been paying attention at mass when...

Darwiniana

100 Easy Lessons

Noogs's reading is coming along nicely. We did lesson 46 today, which involved a story about sacks and sacks of rocks and an old man. (The mild absurdity of the stories is a big selling point with me; I recall my younger siblings starting off with "Go. Go. Go. See Ann run. Run, Ann, run!") Noogs is enthusiastic about reading the stories and would happily skip the practice words and letter sounds, but I think the practice is good for her -- and it builds character, as Calvin's dad would say.

She's been making great strides in putting the sounds together to make words, and now can do so in her head most of the time. When we read a book together, I have her read the words that are easy enough for her, though this only lasts as long as she'll cooperate. And every now and then she'll suprise me. The car seat was inside yesterday and she was playing on it. Suddenly she looks up at me and says, "Push!"

Push what? I asked.

"It says 'push'," she replied, and pointed to the car seat, which did indeed instruct one to push some button.

Mr. Bones

Both Noogs and Babs have become interested in anatomy, and want to read books about skeletons and the human body and muscles. This isn't just confined to the human body, actually -- just last night Noogs was intently studying a picture of a gorilla skeleton and pointing out the skull. At first I wondered if pictures of skinless bodies would scare them, but then, why should they? I don't think I was much of a child for skeletons and muscles, but if that's what they want to learn about then I'm glad to encourage them.

Babes in Toyland

Baby is a treat. She's very placid and seems to take everything in her stride (except when she has to wait longer than she deems acceptable for her meals). Everything's about par for a three week-old baby. I can't wait until she really looks at us and smiles, but she's getting there, she's getting there. Noogs and Babs are delighted with her, and from time to time Noogs will take it into her head to bring me the baby. "Here, Mommy!" she says, holding baby in her arms much as one would carry a log. This is most alarming for me.

Baby has acquired the sometime nickname of "Judy", after a very minor character in Dicken's Bleak House. There's no good reason for this, just as there's no real reason why the older girls should be called Noogs and Babs. In our house, Nicknames Happen.

Thursday, March 23, 2006

Science, the Classroom and the Judge

On one point, Plantinga scores easy points, there is something a bit odd about a judge consulting legal definitions and precedents to try to determine ID "is" science. Science is a field of study, not a legally mandated category, and so any attempt to do this will run into certain problems and end up looking rather silly. This is the problem we run into when we have schools which are not merely government funded but government administered. And yet, who wants to fund something he can't control?

However, as he moves into his analysis of why Jones' conclusion that ID isn't science is flawed, Plantinga himself goes in for what strikes me as some sloppy reasoning. For instance:

First, he said that ID is not science by virtue of its "invoking and permitting supernatural causation." Second, and connected with the first, he said that ID isn't science because the claims IDers make are not testable -- that is verifiable or falsifiable. The connection between the two is the assertion, on the part of the judge and many others, that propositions about supernatural beings -- that life has been designed by a supernatural being -- are not verifiable or falsifiable.Perhaps Plantinga's degree of certainty that statements about the supernatural are testable and falsifiable has allowed him to pick a poor example, but this one seems to me to fall short. There are several layers of statement here which can be tested with varying degrees of success. For instance, there is the statement that "800-pound rabbits live in Cleveland" which we may very much doubt, but we cannot absolutely prove. (At best, we can show that no one has yet successfully found an 800 pound rabbit living in Cleveland.) Then, there is the question of God "designing" the rabbit. Should be find the over-inflated lupine, how exactly can we be sure that God designed it? If we believe (as I do) that God created the universe and holds it in existence through a constant act of the will, we may say (accepting that belief as true) that God designed the rabbit in that sense. But how exactly can we be sure that God designed it in the more immediate sense which I assume Plantinga is using -- namely that he created the rabbit ex nihilo? Even if we were standing in a field and saw the rabbit suddenly appear amid a flash of light, a blare of trumpets, and the echoing words "This is my beloved rabbit, which is rather larger than the normal variety" we would only "know" that the rabbit was created by God to the extent that we assumed with confidence that no other being was capable of putting on such a show for our benefit. (Before anyone says this is a total no brainer and that no one but God can work miracles, I would suggest that Muhammad must, unless he was a conscious fraud or totally insane, have seen or heard some impressive things performed by someone -- and yet as Christians we must doubt that this person was indeed God or the Angel Gabriel.)

... askinging these notions in a rough-and-ready way we can easily see that propositions about supernatural beings not being verifiable or falsifiable isn't true at all.

For example, the statement "God has designed 800-pound rabbits that live in Cleveland" is clearly testable, clearly falsifiable and indeed clearly false.

Continuing to argue that science indeed may include supernatural agents in its calculations, Plantinga argues thus:

Does this important and multifarious human activity by its very nature preclude references to the supernatural? How would anyone argue a thing like that?Now, with all due respect, what Newton was doing in this case was not including supernatural agency in his theory per se.

Newton was perhaps the greatest of the founders of modern science. His theory of planetary motion is thought to be an early paradigm example of modern science. Yet, according to Newton's own understanding of his theory, the planetary motions had instabilities that God periodically corrected. Shall we say that Newton wasn't doing science when he advanced that theory or that the theory isn't a scientific theory at all?

Rather, he was indulging in that age-old activity of fudging what he couldn't explain. His theories of motion came very, very close to explaining all the observable evidence, but not quite. So he went ahead and ran with the theory and said that the remaining gaps were probably filled by divine intervention.

Rather, he was indulging in that age-old activity of fudging what he couldn't explain. His theories of motion came very, very close to explaining all the observable evidence, but not quite. So he went ahead and ran with the theory and said that the remaining gaps were probably filled by divine intervention.Plantinga correctly discerns that the disconnect is in determining exactly what science is supposed to achieve in the first place:

Some say the aim of science is to discover and state natural laws. Others, equally enthusiastic about science, think there aren't any natural laws to discover. According to Richard Otte and John Mackie, the aim of science is to propose accounts of how the world goes for the most part, apart from miracles. Others reject the "for the most part" disclaimer. How does one tell which, if any, of these proposed constraints actually do hold for science? And why should we think that methodological naturalism really does constrain science? And what does "science" really mean?Clearly, that's a pretty broad definition. By that criteria, many branches of 'socal studies' might be considered 'science'. And if so, well and good, perhaps. But I still think there's a useful distinction to be mpursuitseen wider persuits of the "truth about our worllimitedhe rather limitted ambition of formulating theories which allow one to make successful predictions about how physical systems willlimited And that limitted field, whatever one wants to call it, is clearly a field which cannot successfully answer the question "Did God design this?"

I don't have the space to give a complete answer -- as one says when he doesn't know a complete answer -- but the following seems sensible: The usual dictionary definitions suffice to give us the meaning of the term "science." They suggest that this term denotes any activity that is:

(a) a systematic and disciplined enterprise aimed at finding out truth about our world, and

(b) has significant empirical involvement. Any activity that meets these vague conditions counts as science.

One may argue, and perhaps correctly, that in our contemporary culture the concept of 'science' has been given so much power (indeed, many consider it the only way of knowing anything) that to leave metaphysical questions out of it is the same as denying that metaphysical questions exist. (I think of this as the "if science can't tell us about God what good is it" school of thought.) However, if one accepts this widened mandate for 'science' one must eventually define some subgroup of it ("natural science" or "physical science" or "methodological naturalism") which fills the place which people such as Ruse suggest science as a whole fills. And so, in a sense, why bother? The essential thing, it seems to me, is to be clear on the necessity of other fields of inquiry other science -- that indeed one cannot live a human life while knowing only what "science" tells us. Indeed, that "science" tells us very little about what we truly love and value.

Plantinga concludes:

...[I]f you exclude the supernatural from science, then if the world or some phenomena within it are supernaturally caused -- as most of the world's people believe -- you won't be able to reach that truth scientifically.To me, this seems no more worrisome than saying "Metaphysics cannot tell you at what rate a canon ball, dropped from a skyscraper, will plummet toward the earth." But if one expects from science (or whatever one wants to call what most scientists call science) a full view of the truth about the world, it becomes a worrisome in the extreme.

Observing methodological naturalism thus hamstrings science by precluding science from reaching what would be an enormously important truth about the world.

UPDATE: If you're curious to read more about Alvin Plantinga's thought in re the evolution question, he has a lengthy paper on the topic here.

Wednesday, March 22, 2006

Picture on a Shelf

In this digital age, I'm not sure how many people have this problem, but I am anachronistic in that I only shoot film, and only use manual focus SLR cameras. That gives me a level of control over my photos that isn't available in digital cameras that retail under $500. And besides, I just like film. I like prints -- especially medium grain matte finish prints. I like the slightly pebbled colors of low light exposures, the purity of B/W greytones. If I had the time and space, I'd set up a darkroom like I did in highschool and college and develop B/W myself.

The other night, after finding the girls running around with some newly developed prints of the baby, I snatched the packets and put them high up on the top of a bookshelf in the living room. And in doing so I found, covered in dust, a package of prints I had put away in exactly the same place and matter some months before.

Taking down the old package of prints, I found that they were from just over a year ago, when my parents came out to visit us in Texas. The girls had clearly been at the prints (some were slightly rumpled, though none were heavily creased or drawn-on) and the negatives must have been played with, because many of them were scratched.

One of the powerful things about photographs is the way they preserve a single instant of action for years to come. Once, while going through a box of old family papers from my grandmother's house, I came across a vertically cropped black and white photo of a woman looking out the window of a small house. The photo was unlabelled, by my grandmother had no idea who the woman was. From the clothes, it appeared to be from the '20s or '30s. For the longest time the photo sat on the mantle. It was intriguing, both as a well composed photograph, and because it was a window onto a situation which we did not and could not know the details of. Who was she, and who had taken and kept the picture?

Another compelling aspect of photography is the way in which a photograph can extend an instant in time out to eternity. In the famous Vietnam photograph of a police officer executing a Viet Cong fighter, the victim is forever preserved in the moment of flinching from the blast. No amount of explanation or the circumstances could change the essential image. And each time the viewer returned to the photograph, there he was, recoiling from the instant of death. It is the repetition of the image, the drawing out of that instant that gives the photograph its power. What is at first a shock becomes something feared and anticipated at the same time -- an expected blow falling on a bruise, and the expectation that the blow will fall again, and again, because the instant of that Viet Cong fighter's death will never go away.

This drawing out into eternity can also give photographs a certain wistful or even ghostlike atmosphere. If memory serves, Cicero suggested in the Somnium Scipionis that the memory of the dead is a form of immortality. Yet our memory of the dead is modified by what has befallen since. A photograph, on the other hand, is a window into an instant of the past which remains fixed and vivid. Except in the more formal style of portraits, the dead do not look dead in photographs. Being an image rather than a memory, a photograph shows the subject alive -- a very different thing from a memory, that mental shard that remains with us of someone who used to be alive.

From the dusty package I found on top of that bookcase I found myself looking at a photograph of my father, playing with our eldest daughter -- and with that photograph the contradiction of mortality: The deep and abiding knowledge (understood not only by Christians but by nearly every religion throughout history) that there is in the human person some motive and rational force which is immortal and yet at a certain point leaves the body, that thing which we call a soul.

Somehow the image crystallized the distinction between the soul, so clearly animating the person in the photo, and that which was lowered into the ground one bright morning a year later.

Can I be good?

Say a girl spills milk (as happened this very morning, as a matter of fact). Mom grumbles about it, tells the child to be more careful next time, and starts to wipe it up. Child stands there, looks at the spilled milk, and says, "Can I be good?"

Now I have to confess that this just drives me bonkers. Don't ask if you can be good, just be good! Being good is an action, not a philosophical quandry to be debated with oneself over the puddle of cow juice. But spilling milk is an accident -- asking "Can I be good?" after you've just hit your sister and made her cry is an oxymoron.

The roots of this probably spring from us asking the girls in church, "Can you be good?" after they've had to be taken out and spoken to. Still, I can legitimately ask someone else, "Can you be good?" One shouldn't have to ask oneself, "Can I be good?" Either you are being good or you aren't! Make up your mind!

Grr....

Tuesday, March 21, 2006

Natural Religion, Unnatural Science

McCauley argues that the methods and tools modern scientists developed for their daily routines did not arise inevitably in the course of our history, and further, he writes that the more rarefied and esoteric that branches of science become, the less meaning they have for everyday people. It makes no difference, for example, that appeals to the empirical verifiability of a theory like Darwin's vs. the narrative in the Book of Genesis are more persuasive because they can be tested. A careful correct explanation of Natural Selection is far more difficult to get across than the world being created in six days. Likewise quantum mechanics makes no more sense to Joe Sixpack than a careful explanation of the Roman Catholic doctrine of Transubstantiation. Ironically, Dennett draws attention to this in his book but doesn't seem to be aware that explaining the origins of religious belief doesn't make explaining the origin of species any easier or more palatable to most people.There's much more, and all very worth reading.

The Almighty Mortgage

Once upon a time a real estate mortgage was much like a car loan is today (or much like I treat a car loan at any rate) in that you saved a lot of money on the front side, you took out a loan for a fairly short term (in 1952 my dad's parents bought their house with a ten year loan) and you tried hard to pay off the loan early so that you could get control of your income back.

As the price of land and the frequency of moving has increased in urban and suburban areas, people have increasingly come to assume that they will always be making mortgage payments.

Now, I don't even count as an amateur economist, but imagine that you owned your home outright, and that land values were much lower (so your property taxes wouldn't eat up almost 10% income -- after income tax and social security and Medicare tax -- funny how that t-word keeps coming up, eh?). Here in the Darwin household, about 40% of my income goes to mortgage, property taxes and homeowners insurance (which would also be less of a deal if we weren't all so in debt for our homes).

Now, one of the things that got me thinking about this was looking at the huge portions we got when someone brought us Eat Out In the other night. (Having babies gets one all sorts of perks.) My first thought was, "Well, with the amount they charge, there ought to be a lot of food." But then as I thought about it, I realized that the cost of food is really pretty negligible for a restaurant. Their big costs are facilities (rent, equipment, furnishing, etc) and staff. Restaurant food is expensive not because you get a lot of it, but because the cost of facilities and labor (which in turn is expensive because all those people either have mortgages or are paying rent to people who have mortgages) necessitate a high meal cost, and so they give you plenty of food to make you feel better about paying so much.

Health experts of widely blamed restaurants for contributing to America's obesity problem, from supersize shakes at McDonalds to the huger portions served at many mid and even upper range restaurants. However, I wonder if this drive towards larger portions is in great part driven by the rise in property values and the accompanying increases in labor costs and facilities costs. When McDonalds asks you to supersize for 65 cents more, the extra cost of shake and fries is probably only five or ten cents. The big advantage for them is that they have fifty cents more on your order to help pay the $7/hr the guy at the drive-thru window is making, and the $3000/mo they pay in lease on their building. It costs them almost nothing extra to give you the extra food, and they don't have to simply raise prices on the same amount (though they do that as well, goodness knows).

Ironically, the same attempt to pay for facilities and labor is what drives the push towards higher end food that can be seen in everything from McDonalds all breast meat nuggets to Starbucks and Macaroni Grill. Upping the quality of the food ups your costs at a lower rate than it ups your ability to charge for the product. So while a $1 hamburger may have cost $0.25 for the meat, bun and wrapper, a $3.95 burger costs $0.65 for meat, bun, lettuce, tomato, bacon and wrapper. So the margins go up, plus you're applying the margin to a larger dollar amount, which means more margin dollars. Most importantly, it doesn't necessarily take your kitchen staff much more time to make the $3.95 burger than the $1 burger -- so your labor and facility costs remain the same.

That is one of the reasons Starbucks makes so much money. They found a way to get people to pay $3.25 for a cup of coffee when previously people picked up coffee for $0.50. The incremental cost of materials for a latte over a cup of percolated sludge is less than the incremental difference in the price, so Starbucks has more money to sink into nice facilities to attract customers and shareholder profits. (Sadly, the person behind the counter doesn't seem to get much more money from Starbucks than from 7-11, except the ability to say he works at a coffee house rather than a convenience store.)

I'm not sure there's any sort of prescription that can be drawn out of all this. Essentially what it seems to mean is that in an expanding economy land values go up (because more people want to life in the same amount of space) and then your economy shifts so that the cost of goods is increasingly determined by the cost of labor and land (with the former being inflated by the latter) more than by the cost of raw materials.

Monday, March 20, 2006

Trojan Man

Here's this young guy and girl. They want to be close to one another, but there's this damn chain link fence in the way. Trying to kiss through a fence looks pretty silly, and I'm guessing (not having done this sort of thing myself) that's it's rather unsatisfying. There's a barrier between them blocking the completeness of their embrace. Perhaps the symbolism the producers were looking to evoke was an image of playing it safe, but frankly, a fence is a fence is a fence. Something is standing between the guy and the girl, and any expressions of love are going to be truncated until they can find the gate, or until the guy decides that the girl is worth the effort of climbing the fence.

The Theology of the Body talks about the intrinsic meaning of sex. On a spiritual level it's an image of the love Christ has for the Church; even at a purely physical level it says, "I love you and I give myself to you completely, without reservation." Using birth control to withhold one's fertility makes a lie of the objective meaning of sex. Regardless of the intention in using a condom or the pill or the patch (to space children, financial reasons, a one-night stand), birth control is the fence between the couple.

Funny that a Trojan condom commercial should recognize that.

Protecting (some) Children

Currently, a child abused by his Colorado school teacher may only seek redress if he reports the abuse within 180 days of its occurrence.

When one 17-year-old testified about how he was abused by the former school board president of his high school, the panel chairman (Sen. Ron Tupa, himself a social studies teacher in Colorado's Boulder Valley School District) stood up and walked out. However, he later assured reporters that he had seen no information to suggest there was any problem with sex abuse in public schools.

Nice to know everyone has the best interests of children at heart...

Sunday, March 19, 2006

The Best of All Possible Worlds

If I compare myself to a life in which I would have everything I have now, my friends and education, plus Paris Hilton's dog and Bill Gates' stock portfolio, the emotional outcome is assured --Personally, I despise Paris Hilton's dog, but the line about being cursed with Paris Hilton's education and Bill Gates' wardrobe made me laugh out loud.

I will feel miserable, and deprived.

If I think about the actualities and imponderables from which I have been spared -- Paris Hilton's education and Bill Gates' wardrobe -- life looks quite rich.

Let our accountings be approximate, and realistic. Surprisingly, reality-orientation produces less red ink and many more optimistic & grateful footnotes of anticipated future profit.

Elsewhere, Dilys links to a nicely pointed article at TCS entitle The Night I Became An American -- at least in the eyes of European cultural prejudices...

In Which Darwin's Nationalism Is Defeated

For those of you who don't spend your time thinking about quality beer (Pabst drinkers, this means you), Murphy's is an Irish stout in style, but less bitter than Guinness Extra Stout and thicker and maltier than the (to my taste somewhat thin) Guinness Pub Draught (the stuff in pressurized bottles and cans). Murphy's does not have the semi-divine properties of Samuel Smith's Taddy Porter or Oatmeal Stout, but it's pretty solidly good stuff.

So I set out to HEB (our local central Texas supermarket chain, with a fairly decent beer selection). Huge displays of Guinness and Harp (why the Irish saw the need to create a bloody lager I can't imagine) but no Murphy's.

Undaunted, I tried the Twin liquors next door. No Murphy's. My anger grew and I tried World Market and two liquor stores. No Murphy's.

Now it was personal. I tried Albertsons, Randalls and two more liquor stores. No Murphy's.

By this point I was 45 minutes late for the party, so I gave up and headed on over empty handed.

What gives? Hasn't anyone heard that there's more than one brand of Irish stout? And while I'm complaining, why is it that everyone featured huge displays of Bass Ale for St. Patrick's Day? I don't deny that Bass is good, but after 600 years of fighting for our independence you'd think the bloody Brits could keep themselves to themselves one day a year...

Friday, March 17, 2006

Conservative Majority?

But more interestingly (at least to me) he emphasized that one of the reasons the conservative coalition is inherently unstable is that the majority of the country is not in fact 'conservative':

The simple, tragic fact is that conservatism isn't popular. It just ain't. (Nor is doctrinaire liberalism, to be sure.) If you drafted a political program designed to implement National Review's idea of nirvana, it would get crushed at the polls. Americans like government more than card-carrying conservatives do. They value security where libertarians celebrate freedom, and they celebrate freedom where conservatives emphasize virtue.Thus, the current dominance of the Republican party is not so much a result of the majority of the voters actually adhering to any particular brand of conservatism, but rather because the mix of programs and opinions currently coming out of the conservative coalition appeals more (on the whole) to the populace than what they're hearing from the liberal coalition.

Irish fiddling

And speaking of Irish music, here's a link or two for you. If you've been looking for some sheet music so you can play along with the boys in the band, here's The Session, a fine website for exchanging Irish music. Meanwhile, for those of you looking to hire a fine band for all your Irish festivities, I present for your consideration Easter Rising, featuring those upright young men from the Pontifical College Josephinum jamming to a distinctively Celtic beat. The aforementioned boys in the band include John and Will Egan, my younger-but-not-smaller brothers. Bottoms up, bros!

Pro Familia + 1 Filia

Thursday, March 16, 2006

Taliban at Yale

Even Yale isn't defending its action by suggesting that Mr. Rahmatullah has recanted all of the extremist views he espoused during a propaganda tour the ambassador made of the U.S. a few months before 9/11. No one at the International Education Foundation, the Wyoming-based group that is sponsoring his stay in the U.S., will explain an essay Mr. Rahmatullah wrote last year that appeared on its Web site (since removed) in which he called Israel "an American al Qaeda" aimed at the Arab world. In that essay he also claimed the Taliban "did what they had been taught to do. Whether what they had been taught was good or bad is another subject."Maybe it's just that I've been out of the outrageous news item circuit for a while, but I hadn't heard about this before. However, I suppose the cynical approach would be to say that it's surprising neither that Yale would be eager to admit a former member of the Taliban, nor that someone with a fourth grade education could pass a US high school equivalency exam -- both of which are, in their rather different ways, sad commentaries on the American education system.

Yale will have more explaining to do to prospective students and their parents late this month when it begins sending out acceptance letters to 1,300 applicants for coveted positions in its undergraduate class of 2010. The highly selective school will also mail out 19,300 rejection letters. "I can't imagine it will be easy for Yale to convince those it rejects that the Taliban student isn't taking a place they could have had," a former Yale administrator told me. Mr. Rahmatullah boasts only a fourth-grade education and a high-school equivalency degree.

Helaine Klasky, a Yale spokeswoman, takes the position that Mr. Rahmatullah is not a freshman, merely a student in a program that doesn't grant degrees but offers participants a 35% to 40% discount on tuition. "We hope that his courses help him understand the broader context for the conflicts that led to the creation of the Taliban and its fall," she says.

From Athens to Advertising

There are a few aspersions cast at "Christian guilt" which I think are both incorrect and cliched in their analysis, but the central point of the article is interesting. The author suggests that although elite classical Greek culture was shot through with homosexuality (and the cult of the male body in Greek art may have had something to do with that) Greek statues themselves tended to be extremely idealized (tying in with the theme of seeking the ideals found in the Platonic philosophy). Renaissance statues, on the other hand, while taking the nude male subject matter from antiquity, were often clearly based on specific individuals (Donatello's David is one of the examples given) and thus brought a sexual tension to the genre not found in classical art.

Hitting the Big Time

On the bright side, I followed Dreher's recommendation to a very good coffee roaster mail order place.

Patent Pending

At first blush, this might seem like a classic case of the small entrepreneur being stepped on by a mega-corporation and then being helped by the US Patent Office to receive compensation except for one thing: There is no competitive product you can go buy from NTP. NTP has never manufactured a wireless email product. Indeed, they've never manufactured any product. All they do is hold patents.

Not only that, but the US Patent Office is currently investigating NTP's patents and is considered likely to invalidate some or all of their claims. Thus, one of the provisions that NTP insisted on in the settlement was that it not be refundable if the patents were invalidated. (RIM had asked the judge in the case not to issue a BlackBerry shutdown order until the status of the patents was resolved, but the judge refused.)

The RIM/NTP battle is just one instance of an increasingly common phenomenon in the technology sector: 'inventor' companies filing excessively vague patents, never developing any salable product, and then suing any company and develops similar technology. This has caused many in the business world to say that US Patent law requires a fundamental revision -- a concern touched on by this Wharton Business School article on the NTP/RIM case.

The patent office was established based on the constitution's prescription that laws be made "To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries."

The current US Patent situation is described by the USPTO thus:

A patent for an invention is the grant of a property right to the inventor, issued by the United States Patent and Trademark Office. Generally, the term of a new patent is 20 years from the date on which the application for the patent was filed in the United States....Historically, the patent process has proved important in allowing inventors of important products and technologies to get their products to market and establish themselves before being overwhelmed by a wave of imitators who have the advantage of not having had to invest time in research and development.

The right conferred by the patent grant is, in the language of the statute and of the grant itself, "the right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling" the invention in the United States or "importing" the invention into the United States. What is granted is not the right to make, use, offer for sale, sell or import, but the right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, selling or importing the invention. Once a patent is issued, the patentee must enforce the patent without aid of the USPTO.

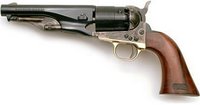

One example which certain readers appreciateiate is that of Samuel Colt and the invention of the 'cap-and-ball' revolver. Colt patented the percussion cap revolver in 1836. That gave him a 20-year lock on the market for a pistol with a revolving cylinder with 5 or 6 chambers closed at the back with an opening on which a percussion cap could be fitted for each chamber and a mechanical cocking device which both advanced the cylinder and prepared the hammer to fall. (Smith & Wesson gained the patent for a revolver with through-bored cylinders into which rimfire cartridges could be loaded.)

One example which certain readers appreciateiate is that of Samuel Colt and the invention of the 'cap-and-ball' revolver. Colt patented the percussion cap revolver in 1836. That gave him a 20-year lock on the market for a pistol with a revolving cylinder with 5 or 6 chambers closed at the back with an opening on which a percussion cap could be fitted for each chamber and a mechanical cocking device which both advanced the cylinder and prepared the hammer to fall. (Smith & Wesson gained the patent for a revolver with through-bored cylinders into which rimfire cartridges could be loaded.)During those twenty years, Colt became a dominant American brand and built itself into a company which would go on to build some of the most famous and trusted guns in American history. It also fought off as many imitators as possible in court, since numerous companies tried to copy their design.

Here's a picture of the 1860 Army model Colt. During the Civil War, the union purchased 107,000 from Colt for $13.75 a piece.

Here's a picture of the 1860 Army model Colt. During the Civil War, the union purchased 107,000 from Colt for $13.75 a piece.In 1857, the market opened up for other reputable competitors to enter the field. Remington (already a well known gun maker) immediately entered the market with a percussion cap revolver which built on Colt's design but added significant improvements, most notably a solid frame which made the gun stronger, provided a more reliable sight (the Colt's sight was just a groove cut in the cocking hammer), and the ability to switch out an empty cylinder for a loaded one in seconds.

The 1863 Remington Army Model revolver (I bought a working replica from Dixie Gun Works many years ago, a nice, fun-to-shoot gun) was one of the most prized guns in the Civil War. The Union bought 125,300 during the war. (Site on Civil War revolvers.)

The 1863 Remington Army Model revolver (I bought a working replica from Dixie Gun Works many years ago, a nice, fun-to-shoot gun) was one of the most prized guns in the Civil War. The Union bought 125,300 during the war. (Site on Civil War revolvers.)Now that, it seems to me, is pretty much how the patent system is supposed to work. The patent provides the inventor with a period of protection during which he can bring his product to market, and at the end of that time the market opens up and others can freely improve on the produce without paying any licensing to the original inventor. However, these days there's another approach that more and more 'inventors' are taking. For instance, back in 2002 a company named PanIP (which didn't sell any products, but had a couple patents which they maintained covered pretty much all forms of ecommerce) began suing random small companies with webstores demanding that they pay $30,000 in licensing for the right to have a website that sold things.

An increasing number of people seem to think that this kind of 'intellectual property' is a viable way to make some money. For instance, check out the top comment on this post about the BlackBerry settlement.

Maybe it's having spent some time trying to break into freelance writing a while back, but it seems pretty clear to me that ideas are dcheapheep. Everyone thinks he has great ideas. But it's not having the idea that's important, it's turning that idea into something, whether it's a short story or a gadget or a business model. Thinking about how to do something, filing a patent for it, and then sitting around to see if someone else (without knowing you exist) invents the same thing and makes a successful business of it so you can sue him is not being an inventor, it's abusing the legal system to be an economic leach.

I'm sure the answer to the problem isn't simple. You want the patent system to give protection to an inventor who is seeking help from a larger company to market his invention, and thus, you can't limit patents to people who already have a commercial product. And yet, you also don't want people who've never made any effort to commercialize a product that they happened to think of to run aroharassingsing those who genuinely have invented a product and brought it to market.

But however the system is supposed to work, it sure sounds to me like the Blackberry case is a good example of how it shouldn't.

Tuesday, March 14, 2006

The BBC vs. the Pirates

Before WW2:

... The English language evening broadcasts from Radio Luxembourg were intentionally beamed toward the British Isles by Luxembourg licensed transmitters, while the intended audience in the United Kingdom originally listened to their radio sets by permission of a Wireless License issued by the British General Post Office (GPO). However, under terms of that Wireless License, it was an offense under the Wireless Telegraphy Act to listen to unauthorized broadcasts such as those transmitted by Radio Luxembourg. Therefore as far as the British authorities were concerned, Radio Luxembourg was a "pirate radio station" and British listeners to the station were breaking the law....

And after:

...the new Postmaster General Edward Short immediately pushed through legislation making it illegal for British citizens and companies to work for, supply, or advertise on an offshore radio station. While the bill was going through parliament, the Post Office summonsed all the fort based stations for broadcasting without a licence. The authorities now decided to use the powers gained in 1964 putting the forts within territorial waters. After long court battles all the stations were forced to close. Two forts remained in international waters, and one of these became the place of violent battles, as two stations vied for control. The other was blown up by the British Army in 1967.

The new anti pirate legislation became law on August 15th 1967, and all the stations except Radio Caroline closed down, knowing they could not survive financailly. On the Isle of Man, the Manx government tried to avoid the new law being imposed by Westminster, and a bitter battle ensued. They were forced to ratify the law which came into effect on the Isle of Man two weeks after the mainland.

The Marriage Gap

Of the last seven presidential elections, Republicans have won five -- three times with more women's votes than the Democrats. For all the rhetoric about the mighty gender gap -- Democratic strategist Ann Lewis once called it ''the Grand Canyon of American politics" -- Republicans seem to bridge it without difficulty.There's a similar pattern with men, though it isn't as distinct. Single and divorced men vote more Democratic than married men. And married couples with children vote more Republican than married couples without.

That's because women aren't monolithic voters, as O'Beirne emphasizes, and they don't march in lockstep to the beat of liberal drums. The best evidence of that is the electoral gap that really does matter in American politics -- the gap separating married women from those who are single.

Unlike the gender gap, there is nothing illusory about the marriage gap. Married women are more likely to vote Republican; unmarried women are more likely to vote Democratic. In the most recent presidential election, unmarried women voted for John Kerry by a 25-point margin, while President Bush won the votes of married women by an 11-point margin -- a marriage gap of 36 points.

''Want to know which candidate a woman is likely to support for president?" asked USA Today in 2004, as the Kerry-Bush race was heading into the home stretch. ''Look at her ring finger."

If I recall correctly, the only groups that Kerry actually carried a majority in nationwide were unmarried women and ethnic minorities. All other groups (married and unmarried men, married women) he lost, though he lost some worse than others.

A Matter of Choice

The interesting thing about this suit is that it points out the inherent contradiction's in the current legal understanding of sex in the United States. On the one hand, a woman must be given a 'choice' as to whether or not to be pregnant after she has already conceived, and so abortion is legally mandated. On the other hand, a man is considered to have already made himself financially liable for any children conceived from the moment that he has sex. Thus, in the man's case, US law recognizes a traditional understanding of what sex is (an act that can naturally be assumed to be fertile) while in the woman's case sex is merely considered an act which may bring on a transitional condition in which a woman has conceived yet has not yet decided whether or not she wants to actually be pregnant.

Clearly, being pregnant (and caring for a child) is a far, far greater burden for a woman than for a man, so one can see how (thinking with its heart rather than its head) our country got itself into this position. But it's still a pretty untenable position to be in. Clearly, one must say either than sex is an act which has the inherent potential to create another human person, or it is not. One of these positions, of course, has the benefit of being true, while the other might be convenient for some, but is quite provably false.