A New York Metro article (which someone linked to several days ago, and I've by now forgotten who) chronicles the three golden ages of abortion in New York City.

In the 1860s and 1970s:

New York's nineteenth-century abortionists advertised openly in the leading newspapers of the day, including the Times. "Ladies who desire to avail themselves of Madame Despard's valuable, certain and safe mode of removing obstructions, suppressions, &c., &c., without the use of medicine, can do so at one interview," read an 1863 Times ad. Abortion advertising became a hefty source of newspaper revenue. New York's most famous abortionist, the flamboyant Madame Restell, spent $60,000 a year on such advertising. Over 40 years, she built an abortion empire, with traveling salesmen hawking her pills and franchise clinics in Boston and Philadelphia. Such was her prominence that abortion was referred to in New York as "Restellism." The practice became very common. A study from 1868 found that one in five New York City pregnancies ended in abortion.Again in the 1960s and 1970s:

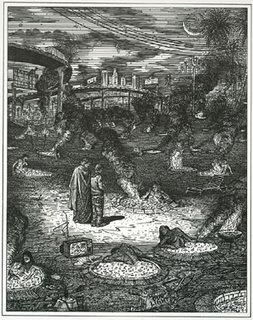

But Restellism produced a backlash. In the 1870s, the Times stopped accepting abortion ads and launched a crusade against the industry. "There is a systematic business in wholesale murder conducted by men and women in this City, that is seldom detected, rarely interfered with, and scarcely ever punished by law," read a front-page report from 1871 headlined THE EVIL OF THE AGE. Laws against abortion advertising were passed, and abortionists were prosecuted. Madame Restell, who had already been through several trials, was arrested again in 1878 for selling her abortifacient concoctions. On the eve of a court appearance, she dressed herself in diamonds, slipped into her marble bathtub, and slit her throat. By 1881, New York had passed some of the most severe abortion bans, laws that were imitated throughout the nation.

As the New York State Legislature moved haltingly toward repealing the state's laws, the city's abortion underground began making news. In 1969, police raided the 30th floor of the New York Hilton and arrested three people performing abortions. Another raid in a luxury high-rise in Riverdale broke up "an abortion ring" servicing wealthy women from around the country, many of whom were referred there by the clergymen.And again now, as New York once again regains its status as one of the few areas in the country where abortion totally on demand (and state funded) is the norm:

When the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL) was founded in 1969, it made New York its first target. Several states had already passed reform laws, but for the most part they allowed abortions only if the health of the mother was at risk. The push for repeal in New York was built in stages, first by the referral system, then by pro-abortion activists converting Democratic clubs in New York City to the cause, precinct by precinct. The turning point in the debate came when several Long Island legislators signed on to the bill. The Times also joined the cause, printing a steady beat of pro-repeal editorials.

The crucial roll call came in the New York Assembly on April 9, 1970. The bill appeared to be doomed by a single vote. As the vote neared completion, a trembling, bespectacled man in a black suit rose to his feet, tears welling in his eyes. "I realize, Mr. Speaker," Assemblyman George M. Michaels said, "that I am terminating my political career, but I cannot in good conscience sit here and allow my vote to be the one that defeats this bill. I ask that my vote be changed from 'no' to 'yes.'" Governor Nelson Rockefeller signed the bill into law, making New York the only state in the country with abortion on demand for all comers.

In the two and a half years between July 1970, when New York's new abortion law took effect, and January 1973, when the Supreme Court's Roe decision legalized the procedure everywhere, 350,000 women came to New York for an abortion, including 19,000 Floridians; 30,000 each from Michigan, Ohio, and Illinois; and thousands more from Canada. By the end of 1971, 61 percent of the abortions performed in New York were on out-of-state residents.

Commercialization crept back into the abortion business. The clergymen, who had never taken any money for their work, were pushed aside by heavily advertised commercial referral services, which targeted out-of-state women, charging them about $100 to find a New York provider. New York's abortion monopoly produced a booming new industry. One service even flew an airplane banner ad over Miami Beach.

The abortion capital of New York is at the corner of Bleecker and Mott. That's the home of Planned Parenthood's Margaret Sanger Center, the largest abortion provider in New York. Doctors at this one clinic perform some 11,000 abortions per year. "I'm sure we provide a good chunk of the abortions in the U.S.," says Dr. Maureen Paul, the chief medical officer of Planned Parenthood New York. In fact, the Margaret Sanger Center provides about one in every ten abortions in New York and about one in every thousand abortions in the United States....And so history's wheel turns round. An interesting irony, which the article elides (I assume it doesn't exactly fit in the author's worldview) is that the progressive/reformist spirit which led to the original bans back in the 1870s was the same spirit which fed the abolitionist movement, the right to vote movement, the labor movement, and the prohibitionist cause -- movements with rather varied degrees of success to be sure, but all of them motivated by the original 'progressive' idea, that simply because "we have always had slavery" or "we have always had drunkenness" or "we have always had abortion" does not mean that one must accept it unrestricted and unfrowned-upon in society.

Over the last year, Dr. Paul has noticed a singular trend: "We are providing more out-of-state abortions." The number of women coming to Planned Parenthood's New York City clinics has risen 21 percent....

Regulating abortion in the United States is like playing whack-a-mole. Every time a state tightens its laws, abortions rise somewhere else. If Roe is overturned, Cristina Page, author of the forthcoming How the Pro-Choice Movement Saved America, estimates that as many as 30 states would likely move toward criminalization, vastly increasing the traffic of abortion seekers into New York, just like in the early 1970s.

Today's 'progressives' retain this idealism on certain topics, believing that it is possible to abolish such things as poverty, war and ethnic prejudice, yet all too many progressives have an old-school fatalism towards other wrongs such as drug abuse and abortion. "Ah well, such things shall always be with us. Might as well keep them safe, legal and rare."

The conservative movement has its own contradictions, holding that human nature and social ills are in many ways constant, and while they should be alleviated cannot be abolished, while at the same time seeking to outlaw certain wrongs (such as abortion), even with the understanding that outlawing them will not make them wholly go away.

No comments:

Post a Comment